Gothic Revival architecture

Sint-Petrus-en-Pauluskerk, Ostend, Belgium, Gothic Revival, 1899–1908

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic or neo-Gothic) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. Its popularity grew rapidly in the early 19th century, when increasingly serious and learned admirers of neo-Gothic styles sought to revive medieval Gothic architecture, in contrast to the neoclassical styles prevalent at the time. Gothic Revival draws features from the original Gothic style, including decorative patterns, finials, lancet windows, hood moulds and label stops.

The Gothic Revival movement emerged in 19th-century England. Its roots were intertwined with deeply philosophical movements associated with Catholicism and a re-awakening of High Church or Anglo-Catholic belief concerned by the growth of religious nonconformism. Ultimately, the "Anglo-Catholicism" tradition of religious belief and style became widespread for its intrinsic appeal in the third quarter of the 19th century. Gothic Revival architecture varied considerably in its faithfulness to both the ornamental style and principles of construction of its medieval original, sometimes amounting to little more than pointed window frames and a few touches of Gothic decoration on a building otherwise on a wholly 19th-century plan and using contemporary materials and construction methods.

In parallel to the ascendancy of neo-Gothic styles in 19th-century England, interest spread rapidly to the continent of Europe, in Australia, Sierra Leone, South Africa and to the Americas; the 19th and early 20th centuries saw the construction of very large numbers of Gothic Revival and Carpenter Gothic structures worldwide. The influence of the Revival had nevertheless peaked by the 1870s. New architectural movements, sometimes related as in the Arts and Crafts movement, and sometimes in outright opposition, such as Modernism, gained ground, and by the 1930s the architecture of the Victorian era was generally condemned or ignored. The later 20th century saw a revival of interest, manifested in the United Kingdom by the establishment of the Victorian Society in 1958.

Contents

1 Roots

2 Survival and revival

2.1 Decorative

3 Romanticism and nationalism

4 Gothic as a moral force

4.1 Pugin and "truth" in architecture

4.2 Ruskin and Venetian Gothic

4.3 Ecclesiology and funerary style

5 Viollet-le-Duc and Iron Gothic

6 Collegiate Gothic

7 Vernacular adaptations

8 20th century

9 Appreciation

10 Details of architectural elements

11 Gallery

11.1 Asia

11.2 Europe

11.3 North America

11.4 South America

11.5 Australia and New Zealand

12 Footnotes

13 References

14 Sources

15 Further reading

16 External links

Roots

The rise of Evangelicalism in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw in England a reaction in the High church movement which sought to emphasise the continuity between the established church and the pre-Reformation Catholic church.[1] Architecture, in the form of the Gothic Revival, became one of the main weapons in the High church's armoury. The Gothic Revival was also paralleled and supported by "medievalism", which had its roots in antiquarian concerns with survivals and curiosities. As "industrialisation" progressed, a reaction against machine production and the appearance of factories also grew. Proponents of the picturesque such as Thomas Carlyle and Augustus Pugin took a critical view of industrial society and portrayed pre-industrial medieval society as a golden age. To Pugin, Gothic architecture was infused with the Christian values that had been supplanted by classicism and were being destroyed by industrialisation.[2]

Gothic Revival also took on political connotations; with the "rational" and "radical" Neoclassical style being seen as associated with republicanism and liberalism (as evidenced by its use in the United States and to a lesser extent in Republican France), the more spiritual and traditional Gothic Revival became associated with monarchism and conservatism, which was reflected by the choice of styles for the rebuilt government centres of the Palace of Westminster (holding the Parliament of the United Kingdom) in London and Parliament Hill in Ottawa.[3]

In English literature, the architectural Gothic Revival and classical Romanticism gave rise to the Gothic novel genre, beginning with The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford, and inspired a 19th-century genre of medieval poetry that stems from the pseudo-bardic poetry of "Ossian". Poems such as "Idylls of the King" by Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson recast specifically modern themes in medieval settings of Arthurian romance. In German literature, the Gothic Revival also had a grounding in literary fashions.[4]

Survival and revival

Tom Tower, Oxford, by Sir Christopher Wren 1681-82, to match the Tudor surroundings.

Gothic architecture began at the Basilica of Saint Denis near Paris, and the Cathedral of Sens in 1140[5] and ended with a last flourish in the early 16th century with buildings like Henry VII's Chapel at Westminster.[6] However, Gothic architecture did not die out completely in the 16th century but instead lingered in on-going cathedral-building projects; at Oxford and Cambridge Universities, and in the construction of churches in increasingly isolated rural districts of England, France, Germany, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and in Spain.[7]

In Bologna, in 1646, the Baroque architect Carlo Rainaldi constructed Gothic vaults (completed 1658) for the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna, which had been under construction since 1390; there, the Gothic context of the structure overrode considerations of the current architectural mode. Guarino Guarini, a 17th-century Theatine monk active primarily in Turin, recognized the "Gothic order" as one of the primary systems of architecture and made use of it in his practice.[8]

Likewise, Gothic architecture survived in an urban setting during the later 17th century, as shown in Oxford and Cambridge, where some additions and repairs to Gothic buildings were considered to be more in keeping with the style of the original structures than contemporary Baroque. Sir Christopher Wren's Tom Tower for Christ Church, University of Oxford, and, later, Nicholas Hawksmoor's west towers of Westminster Abbey, blur the boundaries between what is called "Gothic survival" and the Gothic Revival.[9] Throughout France in the 16th and 17th centuries, churches such as St-Eustache continued to be built following gothic forms cloaked in classical details, until the arrival of Baroque architecture.

Strawberry Hill House, Twickenham, London; a highly influential milestone in Gothic Revival, 1749 by Horace Walpole (1717–1797). It set the "Strawberry Hill Gothic" style.

In the mid-18th century, with the rise of Romanticism, an increased interest and awareness of the Middle Ages among some influential connoisseurs created a more appreciative approach to selected medieval arts, beginning with church architecture, the tomb monuments of royal and noble personages, stained glass, and late Gothic illuminated manuscripts. Other Gothic arts, such as tapestries and metalwork, continued to be disregarded as barbaric and crude, however sentimental and nationalist associations with historical figures were as strong in this early revival as purely aesthetic concerns.[10]

Imitation fan-vaulting in the Gothick Long Gallery at Horace Walpole's Strawberry Hill

German Romanticists (such as philosopher and writer Goethe and architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel), began to appreciate the picturesque character of ruins—"picturesque" becoming a new aesthetic quality—and those mellowing effects of time that the Japanese call wabi-sabi and that Horace Walpole independently admired, mildly tongue-in-cheek, as "the true rust of the Barons' wars." The "Gothick" details of Walpole's Twickenham villa, Strawberry Hill House begun in 1749, appealed to the rococo tastes of the time, and were fairly quickly followed by James Talbot at Lacock Abbey, Wiltshire. By the 1770s, thoroughly neoclassical architects such as Robert Adam and James Wyatt were prepared to provide Gothic details in drawing-rooms, libraries and chapels and William Beckford's romantic vision of a Gothic abbey, Fonthill Abbey in Wiltshire.[11]

Some of the earliest evidence of a revival in Gothic architecture is from Scotland. Inveraray Castle, constructed from 1746, with design input from William Adam, displays the incorporation of turrets. These were largely conventional Palladian style houses that incorporated some external features of the Scots baronial style. Robert Adam's houses in this style include Mellerstain and Wedderburn in Berwickshire and Seton House in East Lothian, but it is most clearly seen at Culzean Castle, Ayrshire, remodelled by Adam from 1777.[12] The eccentric landscape designer Batty Langley even attempted to "improve" Gothic forms by giving them classical proportions.

A younger generation, taking Gothic architecture more seriously, provided the readership for John Britton's series Architectural Antiquities of Great Britain, which began appearing in 1807.[13] In 1817, Thomas Rickman wrote an Attempt... to name and define the sequence of Gothic styles in English ecclesiastical architecture, "a text-book for the architectural student". Its long antique title is descriptive: Attempt to discriminate the styles of English architecture from the Conquest to the Reformation; preceded by a sketch of the Grecian and Roman orders, with notices of nearly five hundred English buildings. The categories he used were Norman, Early English, Decorated, and Perpendicular. It went through numerous editions, was still being republished by 1881, and has been reissued in the 21st century.[14]

Gothic revival campus of the University of Mumbai, India, showing the Rajabai Clock Tower still under construction in 1878

Throughout the 19th and early 20th century, Gothic Revival was used across Europe, throughout the British Empire, and in the United States for public buildings and homes for the people who could afford the style, but the most common use for Gothic Revival architecture was in the building of churches. Churches all over in the countries that were influenced by the Gothic Revival, small and large, whether isolated in small settlements or in the big city, there is at least one church done in Gothic Revival style. Major examples of Gothic cathedrals in the U.S. include the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine in New York City and Washington National Cathedral (also known as "the Cathedral Church of Saints Peter and Paul") on Mount St. Alban in northwest Washington, D.C.. One of the biggest churches in Gothic Revival style in Canada is Basilica of Our Lady Immaculate in Ontario.[15]

Gothic Revival architecture was to remain one of the most popular and long-lived of the many revival styles of architecture. Although Gothic Revival began to lose force and popularity after the third quarter of the 19th century in the commercial, residential and industrial fields, some buildings such as churches, schools, colleges and universities were still constructed in the Gothic style (here often known as "Collegiate Gothic" style) which remained popular in England, Canada and in the United States (the United States has the most of Gothic Revival style architecture for Schools and Colleges/Universities) until well into the early to mid-20th century. Only when new materials, like steel and glass along with concern for function in everyday working life and saving space in the cities, meaning the need to build up instead of out, began to take hold did the Gothic Revival start to disappear from popular building requests.[16]

Decorative

Celestory of the Basilica of the National Vow, Quito, Ecuador

The revived Gothic style was not limited to architecture. Classical Gothic buildings of the 12th to 16th Centuries were a source of inspiration to 19th-century designers in numerous fields of work. Architectural elements such as pointed arches, steep-sloping roofs and fancy carvings like lace and lattice work were applied to a wide range of Gothic Revival objects. Some examples of Gothic Revivals influence can be found in heraldic motifs in coats of arms, painted furniture with elaborate painted scenes like the[17] whimsical Gothic detailing in English furniture is traceable as far back as Lady Pomfret's house in Arlington Street, London (1740s), and Gothic fretwork in chairbacks and glazing patterns of bookcases is a familiar feature of Chippendale's Director (1754, 1762), where, for example, the three-part bookcase employs Gothic details with Rococo profusion, on a symmetrical form. Sir Walter Scott's Abbotsford exemplifies in its furnishings the "Regency Gothic" style. Gothic Revival also includes the reintroduction of medieval clothes and dances in historical reenactments staged among historically-interested followers, especially in the second part of the 19th century, and which have been revived over a hundred years later in the popularity of so-called "renaissance fairs/festivals" in several states (such as in Maryland, Pennsylvania and Virginia). Parties in medieval historical dress and entertainment were popular among the wealthy in the 1800s but has spread in the late 20th century to the well-educated middle class as well.[17]

By the mid-19th century, Gothic traceries and niches could be inexpensively re-created in wallpaper, and Gothic blind arcading could decorate a ceramic pitcher. The illustrated catalogue for the Great Exhibition of 1851 is replete with Gothic detail, from lacemaking and carpet designs to heavy machinery.

In 1847, 8,000 British crown coins were minted in proof condition with the design using an ornate reverse in keeping with the revived style. Considered by collectors to be particularly beautiful, they are known as 'Gothic crowns'. The design was repeated in 1853, again in proof. A similar two shilling coin, the 'Gothic florin' was minted for circulation from 1851 to 1887.

Romanticism and nationalism

Gothic façade of the Parlement de Rouen in France, built between 1499 and 1508, which later inspired Neo-gothic revival in the 19th century

French neo-Gothic had its roots in the French medieval Gothic architecture, where it was created in the 12th century. Gothic architecture was sometimes known during the medieval period as the "Opus Francigenum", (the "French Art"). French scholar Alexandre de Laborde wrote in 1816 that "Gothic architecture has beauties of its own",[18] which marked the beginning of the Gothic Revival in France. Starting in 1828, Alexandre Brogniart, the director of the Sèvres porcelain manufactory, produced fired enamel paintings on large panes of plate glass, for King Louis-Philippe's Chapelle royale de Dreux, an important early French commission in Gothic taste, preceded mainly by some Gothic features in a few jardins paysagers.

Saint Clotilde Basilica completed 1857, Paris

University of Glasgow's main building at Gilmorehill, Glasgow designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott, 1870

The French Gothic Revival was set on sounder intellectual footings by a pioneer, Arcisse de Caumont, who founded the Societé des Antiquaires de Normandie at a time when antiquaire still meant a connoisseur of antiquities, and who published his great work on architecture in French Normandy in 1830 (Summerson 1948). The following year Victor Hugo's historical romance novel The Hunchback of Notre-Dame appeared, in which the great Gothic cathedral of Paris was at once a setting and a protagonist in a hugely popular work of fiction. Hugo intended his book to awaken a concern for the surviving Gothic architecture left in Europe, however, rather than to initiate a craze for neo-Gothic in contemporary life. In the same year that Notre-Dame de Paris appeared, the new French restored Bourbon monarchy established an office in the Royal French Government of Inspector-General of Ancient Monuments, a post which was filled in 1833 by Prosper Mérimée, who became the secretary of a new Commission des Monuments Historiques in 1837. This was the Commission that instructed Eugène Viollet-le-Duc to report on the condition of the Abbey of Vézelay in 1840. Following this, Viollet le Duc set to restore most of the symbolic buildings in France including Notre Dame de Paris, Vézelay, Carcassonne, Roquetaillade castle, the famous Mont Saint-Michel on its peaked coastal island, Pierrefonds, and Palais des Papes in Avignon. When France's first prominent neo-Gothic church[a] was built, the Basilica of Saint-Clotilde,[b] Paris, begun in September 1846 and consecrated 30 November 1857, the architect chosen was, significantly, of German extraction, Franz Christian Gau, (1790–1853); the design was significantly modified by Gau's assistant, Théodore Ballu, in the later stages, to produce the pair of flèches that crown the west end.

Cologne Cathedral, finally completed in 1880 (though construction started originally in 1248) with a façade 157 metres tall and a nave 43 metres tall

Meanwhile, in Germany, interest in the Cologne Cathedral, which had begun construction in 1248 and was still unfinished at the time of the revival, began to reappear. The 1820s "Romantic" movement brought back interest, and work began once more in 1842, significantly marking a German return of Gothic architecture. The Prague cathedral was also completed late.[c][19]

Because of Romantic nationalism in the early 19th century, the Germans, French and English all claimed the original Gothic architecture of the 12th century era as originating in their own country. The English boldly coined the term "Early English" for "Gothic", a term that implied Gothic architecture was an English creation. In his 1832 edition of Notre Dame de Paris, author Victor Hugo said "Let us inspire in the nation, if it is possible, love for the national architecture", implying that "Gothic" is France's national heritage. In Germany, with the completion of Cologne Cathedral in the 1880s, at the time its summit was the world's tallest building, the Cathedral was seen as the height of Gothic architecture. Other major completions of Gothic cathedrals were of Regensburger Dom (with twin spires completed from 1869–1872), Ulm Münster (with a 161-meter tower from 1890) and St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague (1844–1929).

In Belgium, a 15th-century church in Ostend burned down in 1896. King Leopold II supported its replacement by a cathedral-like church after the style of the also Neo-Gothic Votive Church in Vienna and Cologne Cathedral: the Saint Peter's and Saint Paul's Church.[20] In Mechelen, the largely unfinished building drawn in 1526 as the seat of the Great Council of The Netherlands, finally got built in the early 20th century strictly following Rombout II Keldermans's Brabantine Gothic design, and became the 'new' north wing of the City Hall.[21][22]

In Florence, the Duomo's temporary façade erected for the Medici-House of Lorraine nuptials in 1588–1589, was dismantled, and the west end of the cathedral stood bare again until 1864, when a competition was held to design a new façade suitable to Arnolfo di Cambio's original structure and the fine campanile next to it. This competition was won by Emilio De Fabris, and so work on his polychrome design and panels of mosaic was begun in 1876 and completed by 1887, creating the Neo-Gothic western façade. In Indonesia, (the former colony of the Dutch East Indies), the Jakarta Cathedral was begun in 1891 and completed in 1901 by Dutch architect Antonius Dijkmans; while further north in the islands of the Philippines, the San Sebastian Church, designed by architects Genaro Palacios and Gustave Eiffel and was consecrated in 1891 in the still Spanish colony.[23]

In Scotland, while a similar Gothic style to that used further south in England was adopted by figures including Frederick Thomas Pilkington (1832–98)[24] in secular architecture it was marked by the re-adoption of the Scots baronial style.[25] Important for the adoption of the style in the early 19th century was Abbotsford House, the residence of the novelist and poet Sir Walter Scott. Re-built for him from 1816, it became a model for the modern revival of the baronial style. Common features borrowed from 16th- and 17th-century houses included battlemented gateways, crow-stepped gables, pointed turrets and machicolations. The style was popular across Scotland and was applied to many relatively modest dwellings by architects such as William Burn (1789–1870), David Bryce (1803–76),[26]Edward Blore (1787–1879), Edward Calvert (c. 1847–1914) and Robert Stodart Lorimer (1864–1929) and in urban contexts, including the building of Cockburn Street in Edinburgh (from the 1850s) as well as the National Wallace Monument at Stirling (1859–69).[27] The rebuilding of Balmoral Castle as a baronial palace and its adoption as a royal retreat from 1855-8 confirmed the popularity of the style.[28]

In the United States, the first "Gothic stile"[29] church (as opposed to churches with Gothic elements) was Trinity Church on the Green, New Haven, Connecticut. It was designed by the prominent American Architect Ithiel Town between 1812 and 1814, even while he was building his Federalist-style Center Church, New Haven right next to this radical new "Gothic-style" church. Its cornerstone was laid in 1814,[30] and it was consecrated in 1816.[31] It thus predates St Luke's Church, Chelsea, often said to be the first Gothic-revival church in London, by a decade. Though built of trap rock stone with arched windows and doors, parts of its Gothic tower and its battlements were wood. Gothic buildings were subsequently erected by Episcopal congregations in Connecticut at St. John's in Salisbury (1823), St. John's in Kent (1823–26), St. Andrew's in Marble Dale (1821–23).[29] These were followed by Town's design for Christ Church Cathedral (Hartford, Connecticut) (1827), which incorporated Gothic elements such as buttresses into fabric of the church. St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Troy, New York, was constructed in 1827–1828 as an exact copy of the Town's design for Trinity Church, New Haven, but using local stone; due to changes in the original, St. Paul's is closer to Town's original design than Trinity itself. In the 1830s, architects began to copy specific English Gothic and Gothic Revival Churches, and these "mature Gothic Revival" buildings "made the domestic Gothic style architecture which preceded it seem primitive and old-fashioned".[32] Since then, Gothic Revival architecture has spread to thousands of churches and Gothic-revival buildings across America.

There are many examples of Gothic Revival architecture in Canada. The first major Gothic Revival structure in Canada was Notre-Dame Basilica in Montreal, Quebec, which was designed in 1824. During the War of 1812 many homesteads along the St. Lawrence River were destroyed. Most of the homes were built in the Georgian style; after their destruction they were rebuilt in the Gothic Revival or "Jigsaw Gothic" style. The capital city of Ottawa, Ontario is full of Gothic Revival architecture. The Parliament Hill buildings which were built in the last decades of the 19th century were built in the Gothic Revival style, as were many other buildings in the city and outlying areas, showing how popular the Gothic Revival movement had become.[15] Other examples of Canadian Gothic Revival architecture are the Victoria Memorial Museum, (1905–08), the Royal Canadian Mint, (1905–08), and Connaught Building, (1913–16), all in Ottawa by David Ewart.[33][34]

Gothic as a moral force

Pugin and "truth" in architecture

The House of Lords in the Palace of Westminster, designed by A. W. N. Pugin

In the late 1820s, A. W. N. Pugin, still a teenager, was working for two highly visible employers, providing Gothic detailing for luxury goods.[35] For the Royal furniture makers Morel and Seddon he provided designs for redecorations for the elderly George IV at Windsor Castle in a Gothic taste suited to the setting. For the royal silversmiths Rundell Bridge and Co., Pugin provided designs for silver from 1828, using the 14th-century Anglo-French Gothic vocabulary that he would continue to favour later in designs for the new Palace of Westminster.[36] Between 1821 and 1838 Pugin and his father published a series of volumes of architectural drawings, the first two entitled, Specimens of Gothic Architecture, and the following three, Examples of Gothic Architecture, that were to remain both in print and the standard references for Gothic Revivalists for at least the next century.

In Contrasts (1836), Pugin expressed his admiration not only for medieval art but for the whole medieval ethos, claiming that Gothic architecture is the product of a purer society. In The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture (1841), he suggested that modern craftsmen seeking to emulate the style of medieval workmanship should also reproduce its methods. Pugin believed Gothic was true Christian architecture, and even said "the pointed arch was produced by the Catholic faith".

Pugin's most famous project is The Houses of Parliament in London, which was largely destroyed in a fire in 1834.[37][d] His part in the design consisted of two campaigns, 1836–1837 and again in 1844 and 1852, with the classicist Charles Barry as his nominal superior (whether the pair worked as a collegial partnership or if Barry acted as Pugin's superior is not entirely clear). Pugin provided the external decoration and the interiors, while Barry designed the symmetrical layout of the building, causing Pugin to remark, "All Grecian, Sir; Tudor details on a classic body".[39]

Ruskin and Venetian Gothic

John Ruskin supplemented Pugin's ideas in his two hugely influential theoretical works, The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) and The Stones of Venice (1853). Finding his architectural ideal in Venice, Ruskin proposed that Gothic buildings excelled above all other architecture because of the "sacrifice" of the stone-carvers in intricately decorating every stone. By declaring the Doge's Palace to be "the central building of the world", Ruskin argued the case for Gothic government buildings as Pugin had done for churches, though mostly only in theory. When his ideas were put into practice, Ruskin often disliked the result, although he supported many architects, such as Thomas Deane and Benjamin Woodward, and was reputed to have designed some of the corbel decorations for that pair's Oxford University Museum of Natural History.[40]

Ecclesiology and funerary style

Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, an example of Brick Gothic revival

Construction of Washington National Cathedral began in 1907 and was completed in 1990.

In England, the Church of England was undergoing a revival of Anglo-Catholic and ritualist ideology in the form of the Oxford Movement and it became desirable to build large numbers of new churches to cater for the growing population, and cemeteries for their hygienic burials. This found ready exponents in the universities, where the ecclesiological movement was forming. Its proponents believed that Gothic was the only style appropriate for a parish church, and favoured a particular era of Gothic architecture—the "decorated". The Cambridge Camden Society, through its journal The Ecclesiologist, was so savagely critical of new church buildings that were below its exacting standards and its pronouncements were followed so avidly that it became the epicentre of the flood of Victorian restoration that affected most of the Anglican cathedrals and parish churches in England and Wales.[41]

St Luke's Church, Chelsea, was a new-built Commissioner's Church of 1820–24, partly built using a grant of £8,333 towards its construction with money voted by Parliament as a result of the Church Building Act of 1818.[42] It is often said to be the first Gothic Revival church in London,[43] and, as Charles Locke Eastlake put it: "probably the only church of its time in which the main roof was groined throughout in stone".[44] Nonetheless, the parish was firmly Low Church, and the original arrangement, modified in the 1860s, was as a "preaching church" dominated by the pulpit, with a small altar and wooden galleries over the nave aisle.[45]

The development of the private major metropolitan cemeteries was occurring at the same time as the movement; Sir William Tite pioneered the first cemetery in the Gothic style at West Norwood in 1837, with chapels, gates, and decorative features in the Gothic manner, attracting the interest of contemporary architects such as George Edmund Street, Barry, and William Burges. The style was immediately hailed a success and universally replaced the previous preference for classical design.

However, not every architect or client was swept away by this tide. Although Gothic Revival succeeded in becoming an increasingly familiar style of architecture, the attempt to associate it with the notion of high church superiority, as advocated by Pugin and the ecclesiological movement, was anathema to those with ecumenical or nonconformist principles. They looked to adopt it solely for its aesthetic romantic qualities, to combine it with other styles, or look to northern European Brick Gothic for a more plain appearance; or in some instances all three of these, as at the non-denominational Abney Park Cemetery designed by William Hosking FSA in 1840.[46]

Viollet-le-Duc and Iron Gothic

France had lagged slightly in entering the neo-Gothic scene, but produced a major figure in the revival in Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. As well as a powerful and influential theorist, Viollet-le-Duc was a leading architect whose genius lay in restoration. He believed in restoring buildings to a state of completion that they would not have known even when they were first built, theories he applied to his restorations of the walled city of Carcassonne,[47] and to Notre-Dame and Sainte Chapelle in Paris.[48] In this respect he differed from his English counterpart Ruskin, as he often replaced the work of mediaeval stonemasons. His rational approach to Gothic stood in stark contrast to the revival's romanticist origins.

Throughout his career he remained in a quandary as to whether iron and masonry should be combined in a building. Iron had in fact been used in Gothic buildings since the earliest days of the revival. It was only with Ruskin and the archaeological Gothic's demand for historical truth that iron, whether it was visible or not, was deemed improper for a Gothic building.

This argument began to collapse in the mid-19th century as great prefabricated structures such as the glass and iron Crystal Palace and the glazed courtyard of the Oxford University Museum were erected, which appeared to embody Gothic principles through iron. Between 1863 and 1872 Viollet-le-Duc published his Entretiens sur l'architecture, a set of daring designs for buildings that combined iron and masonry. Though these projects were never realised, they influenced several generations of designers and architects, notably Antoni Gaudí in Spain and, in England, Benjamin Bucknall, Viollet's foremost English follower and translator, whose masterpiece was Woodchester Mansion.[49]

The flexibility and strength of cast-iron freed neo-Gothic designers to create new structural gothic forms impossible in stone, as in Calvert Vaux's cast-iron bridge in Central Park, New York (1860s; illustration, below). Vaux enlists openwork forms derived from Gothic blind-arcading and window tracery to express the spring and support of the arching bridge, in flexing forms that presage Art Nouveau.

The upper chapel of the Sainte Chapelle, restored by Félix Duban in the 19th century

Cast-iron gothic tracery supports a bridge by Calvert Vaux, Central Park, New York City.

Collegiate Gothic

The Cathedral of Learning at the University of Pittsburgh

In the United States, Collegiate Gothic was a late and literal resurgence of the English Gothic Revival, adapted for American university campuses. The firm of Cope & Stewardson was an early and important exponent, transforming the campuses of Bryn Mawr College, Princeton University and the University of Pennsylvania in the 1890s.

The movement continued into the 20th century, with Cope & Stewardson's campus for Washington University in St. Louis (1900–09), Charles Donagh Maginnis's buildings at Boston College (1910s), Ralph Adams Cram's design for the Princeton University Graduate College (1913), and James Gamble Rogers' reconstruction of the campus of Yale University (1920s). Charles Klauder's Gothic Revival skyscraper on the University of Pittsburgh's campus, the Cathedral of Learning (1926) exhibited very Gothic stylings both inside and out, while utilizing modern technologies to make the building taller.[50]

Vernacular adaptations

Carpenter gothic Unitarian Universalists of San Mateo, California (built 1905) showing gothic arches, steep gables, and a tower. The tower includes examples of abat-sons.

Vernacular Gothic Revival elements in an 1873 church of the Slavine Architectural School in Gavril Genovo, Montana Province, northwestern Bulgaria

Carpenter Gothic houses and small churches became common in North America and other places in the late 19th century.[51] These structures adapted Gothic elements such as pointed arches, steep gables, and towers to traditional American light-frame construction. The invention of the scroll saw and mass-produced wood moldings allowed a few of these structures to mimic the florid fenestration of the High Gothic. But, in most cases, Carpenter Gothic buildings were relatively unadorned, retaining only the basic elements of pointed-arch windows and steep gables. Probably the best-known example of Carpenter Gothic is a house in Eldon, Iowa, that Grant Wood used for the background of his famous painting American Gothic.[52]

Benjamin Mountfort of Canterbury, New Zealand imported the Gothic Revival style to New Zealand, and designed Gothic Revival churches in both wood and stone. Frederick Thatcher in New Zealand designed wooden churches in the Gothic Revival style, e.g. Old St. Paul's, Wellington. St Mary of the Angels, Wellington by Frederick de Jersey Clere is in the French Gothic style, and was the first Gothic design church built in ferro-concrete. The style also found favour in the southern New Zealand city of Dunedin, where the wealth brought in by the Otago Gold Rush of the 1860s allowed for substantial stone edifices to be constructed, among them Maxwell Bury's University of Otago Registry Building and the John Campbell-designed Dunedin Law Courts, both constructed from hard dark breccia and a local white limestone, Oamaru stone.

Other Gothic Revival churches were built in Australia, in particular in Melbourne and Sydney, see Category:Gothic Revival architecture in Australia.

In 19th-century northwestern Bulgaria, the informal Slavine Architectural School introduced Gothic Revival elements into its vernacular ecclesiastical and residential Bulgarian National Revival architecture. These included geometric decorations based on the triangle on apses, domes and external narthexes, as well as sharp-pointed window and door arches. The largest project of the Slavine School is the Lopushna Monastery cathedral (1850–1853), though later churches like those in Zhivovtsi (1858), Mitrovtsi (1871), Targovishte (1870–1872), Gavril Genovo (1873), Gorna Kovachitsa (1885) and Bistrilitsa (1887–1890) display more prominent vernacular Gothic Revival features.[53]

20th century

The Gothic style dictated the use of structural members in compression, leading to tall, buttressed buildings with interior columns of load-bearing masonry and tall, narrow windows. But, by the start of the 20th century, technological developments such as the steel frame, the incandescent light bulb and the elevator made this approach obsolete. Steel framing supplanted the non-ornamental functions of rib vaults and flying buttresses, providing wider open interiors with fewer columns interrupting the view.

Some architects persisted in using Neo-Gothic tracery as applied ornamentation to an iron skeleton underneath, for example in Cass Gilbert's 1913 Woolworth Building skyscraper in New York and Raymond Hood's 1922 Tribune Tower in Chicago. But, over the first half of the century, Neo-Gothic was supplanted by Modernism, although some modernist architects saw the Gothic tradition of architectural form entirely in terms of the "honest expression" of the technology of the day, and saw themselves as heirs to that tradition, with their use of rectangular frames and exposed iron girders.

In spite of this, the Gothic Revival continued to exert its influence, simply because many of its more massive projects were still being built well into the second half of the 20th century, such as Giles Gilbert Scott's Liverpool Cathedral and the Washington National Cathedral (1907–1990). Ralph Adams Cram became a leading force in American Gothic, with his most ambitious project the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York (claimed to be the largest Cathedral in the world), as well as Collegiate Gothic buildings at Princeton University. Cram said "the style hewn out and perfected by our ancestors [has] become ours by uncontested inheritance."

Though the number of new Gothic Revival buildings declined sharply after the 1930s, they continue to be built. The cathedral of Bury St. Edmunds was constructed between the late 1950s and 2005.[54] A new church in the Gothic style is planned for St. John Vianney Parish in Fishers, Indiana.[55][56] A new building currently under construction in Peterhouse will adopt the neo-gothic style of the rest of the courtyard it is being built in.[57]

Liverpool Cathedral, whose construction ran from 1903 to 1978

Passion Façade of La Sagrada Família in Barcelona, Spain (cranes digitally removed)

Appreciation

By 1872, the Gothic Revival was mature enough in the United Kingdom that Charles Locke Eastlake, an influential professor of design, could produce A History of the Gothic Revival,[58] but the first extended essay on the movement that was written within the maturing field of art history was Kenneth Clark's, The Gothic Revival. An Essay, which appeared in 1928.[59] The architect and writer Harry Stuart Goodhart-Rendel covered the subject of the Revival in an appreciative way in his Slade Lectures in 1934.[60] But the conventional early 20th century view of the architecture of the Gothic Revival was strongly dismissive, critics writing of "the nineteenth century architectural tragedy",[61] ridiculing "the uncompromising ugliness"[62] of the era's buildings and attacking the "sadistic hatred of beauty" of its architects.[63][e] The 1950s saw further small signs of a recovery in the reputation of Revival architecture. John Steegman's study, Consort of Taste (re-issued in 1970 as Victorian Taste, with a foreword by Nikolaus Pevsner), was published in 1950 and began a slow turn in the tide of opinion "towards a more serious and sympathetic assessment."[65] This was followed by the foundation of the Victorian Society in 1958 and, in 1963, the publication of Victorian Architecture, an influential collection of essays edited by Peter Ferriday.[66] By 2008, the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Victorian Society, the architecture of the Gothic Revival was more fully appreciated with some of its leading architects receiving scholarly attention and some of its best buildings, such as George Gilbert Scott's St Pancras Station Hotel, being magnificently restored.[67]

Details of architectural elements

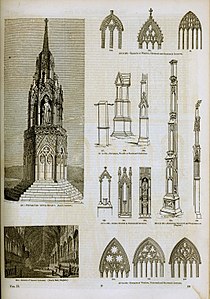

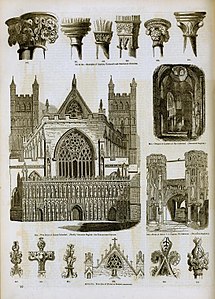

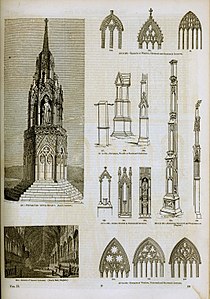

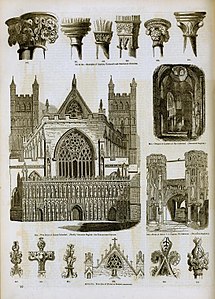

These illustrations are from Charles Knight's Pictorial Gallery of the Arts, published in England in 1858. They show detailed perspectives on the incorporation of modern design influences in the Gothic style:

Architecture and arch elements

Decorative architectural elements

More examples of decorative architectural elements

Gallery

Asia

Basílica Menor de San Sebastián, Manila, Philippines

Church of the Saviour, Baku, Azerbaijan

Georgian Orthodox Cathedral of the Mother of God, Batumi, Georgia

Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (formerly Victoria Terminus), Mumbai, India

Jakarta Cathedral interior in Jakarta, Indonesia

Europe

Hungarian Parliament Building, Budapest, Hungary

Church of St. Ludmila, Prague, Czech Republic

Town Hall, Manchester, England

John Rylands Library, Manchester, England

St. Mark's Church, Royal Tunbridge Wells, England

The Lady Chapel of Liverpool Cathedral, designed by Giles Gilbert Scott overseen by G F Bodley

Vajdahunyad Castle in Budapest, Hungary

Co-cathedral in Osijek, Croatia

Perpetual Adoration Church (Örökimádás templom), Budapest, Hungary

Palace of Culture, Iaşi, Romania

St Pancras railway station, London

New Peterhof railstation building, 1857, Saint Petersburg, Russia

St. Nicholas Cathedral (Catholic), Kiev, Ukraine

Sacred Heart Church, Kőszeg, Hungary, 1892–1894

Tower Bridge, London

Wrocław Główny railway station, 1857, Wrocław, Poland

North America

Salt Lake Temple, Salt Lake City, Utah

St. Patrick's Basilica, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Templo Expiatorio del Santísimo Sacramento Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico

Templo Expiatorio León, Guanajuato, Mexico

Cathedral of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Michoacán, Mexico

Collegiate Gothic buildings of Boston College, United States

Tribune Tower, Chicago

The Notre-Dame basilica of Montreal

South America

The Neo-Gothic Cathedral of La Plata, in La Plata, Argentina, built between 1884 and 2000

Basilica of Our Lady of Luján, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina

The São Paulo Metropolitan Cathedral, São Paulo, Brazil

St. Peter of Alcantara Cathedral, Petrópolis, Brazil

Nuestra Señora del Perpetuo Socorro, a Neo-Gothic Basilic in Santiago of Chile.

Australia and New Zealand

St Paul's Cathedral, Melbourne

Larnach Castle

Footnotes

^ In Montreal, Quebec, Canada, the earlier neo-Gothic Basilica of Notre Dame (1842) belongs to the Gothic Revival exported from Great Britain.

^ The choice of the canonized wife of King Clovis was especially significant for the Bourbons.

^ The importance of the Cologne completion project in German-speaking lands has been explored by Michael J. Lewis, "The Politics of the German Gothic Revival: August Reichensperger"

^ Pugin recorded his delight at the destruction of what he considered the wholly inadequate earlier restorations of James Wyatt and John Soane. "You have doubtless seen the accounts of the late great conflagration at Westminster. There is nothing much to regret...a vast amount of Soane's mixtures and Wyatt's heresies have been consigned to oblivion. Oh it was a glorious sight to see his composition mullions and cement pinnacles flying and cracking."[38]

^ Kenneth Clark, despite his sympathetic approach, recalled that during his Oxford years it was generally believed not only that Keble College was "the ugliest building in the world" but that its architect was John Ruskin, author of The Stones of Venice. The college was built to the designs of the noted architect William Butterfield.[64]

References

^ Curl 1990, pp. 14-15.

^ Pugin and the Gothic Revival at the Wayback Machine (archived 2007-10-06)

^ Cooke 1987, p. 87.

^ Robson-Scot 1965, p. unknown.

^ Furneaux Jordan 1979, p. 127.

^ Furneaux Jordan 1979, p. 163.

^ Furneaux Jordan 1979, p. 165.

^ "Guarino Guarini : Italian architect, priest, mathematician, and theologian". Encyclopedia Britannica. n.d. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

^ Macauley 1975, p. 31.

^ Aldrich 2005, p. 140.

^ Aldrich 2005, pp. 82-83.

^ Whyte & Whyte 1991, p. 100.

^ Macauley 1975, p. 174.

^ Rickman 1848, p. 47.

^ ab Kyles, Shannon. "Gothic Revival (1750–1900)". OntarioArchitecture.com.

^ "Gothic Revival". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

^ ab "Style Guide: Gothic Revival". London, United Kingdom: Victoria and Albert Museum.

^ Bartlett 2001, p. 15.

^ Brichta 2014.

^ "Sint-Petrus-en-Pauluskerk" (in Dutch). City of Ostend. Retrieved 24 July 2011. (Neo-Gothic church)

"Sint-Pieterstoren (Peperbusse)" (in Dutch). City of Ostend. Retrieved 24 July 2011. (West tower of the burnt-down church)

^ "Stadhuis" (in Dutch). City of Mechelen. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

^ "Stadhuis met voormalige Lakenhal (ID: 3717)". De Inventaris van het Bouwkundig Erfgoed (in Dutch). Vlaams Instituut voor het Onroerend Erfgoed (VIOE). Retrieved 24 July 2011.

^ UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "San Sebastian Church - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Web.archive.org. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

^ Stamp 1995, pp. 108-110.

^ Jackson 2011, p. 152.

^ Hull 2006, p. 154.

^ Glendenning, MacInnes & MacKechnie 2002, pp. 276-285.

^ Hitchcock 1989, p. 146.

^ ab Buggeln 2003, p. 115.

^ Jarvis 1814.

^ Hobart 1816, p. 5.

^ Stanton 1997, p. 3.

^ Fulton 2005.

^ Zanzonico, Susan. "Understanding Gothic Revival Architecture". Streetdirectory.com.

^ Aldrich & Atterbury 1995, p. 372.

^ "Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–52)". The Victorian Web. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

^ Hill 2007, p. 317.

^ Atterbury & Wainwright 1994, p. 219.

^ Atterbury & Wainwright 1994, p. 221.

^ Dixon & Muthesius 1993, p. 160.

^ Clark 1983, pp. 155-174.

^ Port 2006, p. 327.

^ Germann 1972, p. 9.

^ Eastlake 2012, p. 141.

^ Parish website, "St Luke's Church – A Brief History", accessed 2 November 2012

^ "ABNEY PARK CEMETERY, Hackney - 1000789". Historic England. 1987-10-01. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

^ Midant 2002, p. 96.

^ Midant 2002, p. 54.

^ "THE MANSION, Woodchester - 1340703". Historic England. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

^ "Cathedral of Learning, Pittsburgh". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

^ Poppeliers, Chambers & Schwartz 1979.

^ "American Gothic House Center". Wapellocounty.org. 18 December 2009. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

^ Тулешков 2007.

^ Pearman, Hugh (13 March 2005). "Return of the Goths: the last Anglican cathedral is nearly finished. And built to last 1,000 years". Gabion: Retained Writing on Architecture. Hugh Pearman. Archived from the original on 18 March 2005.

^ Mooney, Caroline (27 April 2008). "Architectural plans unveiled for church and campus complex over the next two decades". The Catholic Moment. Lafayette, Indiana. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008.

^ "St. John Vianney Fishers, Indiana". HDB/Cram and Ferguson. Archived from the original on 8 October 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

^ Historic England. "Peterhouse (371420)". PastScape. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

^ Eastlake 2012, p. preface.

^ Clarke 1983, p. preface.

^ Steegman 1970, p. V.

^ Turnor 1950, p. 111.

^ Turnor 1950, p. 91.

^ Clark 1983, p. 191.

^ Clark 1983, p. 2.

^ Steegman, p. 2.

^ Ferriday 1963, Introduction.

^ Bradley 2007, p. 163.

Sources

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

Aldrich, Megan Brewster; Atterbury, Paul (1995). A.W.N. Pugin: Master of Gothic Revival. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06656-2.

Aldrich, Megan (2005). Gothic Revival. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-3631-7.

Atterbury, Paul; Wainwright, Clive (1994). Pugin: A Gothic Passion. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06656-2.

Bartlett, Robert (2001). Medieval Panorama. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. ISBN 9780892366422.

Bradley, Simon (2007). St Pancras Station. London: Profile Books. ISBN 9781861979513.

Brichta, Tomas (2014). Late Completion of Cologne and St-Vitus Cathedral (M.Arch). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/9814.

Buggeln, Gretchen Townsend (2003). Temples of Grace: The Material Transformation of Connecticut's Churches. Hanover, US: New England University Publications. ISBN 9781584653226.

Clark, Kenneth (1983). The Gothic Revival: An Essay in the History of Taste. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-3102-6.

Cooke, Robert (1987). The Palace of Westminster. London: Burton Skira. ISBN 9782882490148.

Curl, James Stevens (1990). Victorian Architecture. Newton Abbot, Devon and London: David & Charles. ISBN 9780715391440.

Dixon, Roger; Muthesius, Stefan (1993). Victorian Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-19-520048-5.

Eastlake, Charles Locke (2012). A History Of The Gothic Revival. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-05191-0.

Ferriday, Peter (1963). Victorian Architecture. London: Jonathan Cape. OCLC 270335.

Fulton, Gordon W. (1979–2016). "Ewart, David". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

Furneaux Jordan, Robert (1979). A Concise History of Western Architecture. London: Thames & Hudson. OCLC 757298161.

Germann, Georg (1972). Gothic Revival in Europe and Britain: Sources, Influences and Ideas. London: Lund Humphries. ISBN 9780853313434.

Glendenning, Miles; MacInnes, Ranald; MacKechnie, Aonghus (2002). A History of Scottish Architecture: from the Renaissance to the Present Day. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748607419.

Hill, Rosemary (2007). God's Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 9780713994995.

Hitchcock, Henry-Russell (1989). Architecture: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300053203.

Hobart, John Henry (1816). The Moral Efficacy and the Postitive Benefits of the Ordinances of the Gospel: A Sermon Preached at the Consecration of Trinity Church, in the City of New Haven, on Wednesday, the 21st Day of February, A.D. 1816. Oliver Steele.

Hull, Lise (2006). Britain's Medieval Castles. London: Praeger. ISBN 9780275984144.

Jackson, Alvin (2011). The Two Unions: Ireland, Scotland, and the Survival of the United Kingdom, 1707–2007. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199593996.

Jarvis, Samuel Farmar (1814). An Address, Delivered in the City of New-Haven: At the Laying of the Corner-stone of Trinity Church, May 17th, 1814. Oliver Steele.

Macaulay, James (1975). The Gothic Revival 1745-1845. Glasgow and London: Blackie. ISBN 9780216898929.

Midant, Jean-Paul (2002). Viollet-le-Duc: The French Gothic Revival. Paris: L'Aventurine. ISBN 9782914199223.

Poppeliers, John; Chambers, S. Allen; Schwartz, Nancy (1979). What Style Is It. Washington D. C.: The Preservation Press. ISBN 9780891330653.

Port, M. H. (2006). 600 New Churches: The Church Building Commission 1818–1856. Reading, UK: Spire Books. ISBN 9781904965084.

Rickman, Thomas (1848). An Attempt to Discriminate the Styles of Architecture in England: From the Conquest to the Reformation. London: J. H. Parker. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107338241.

Robson Scott, William Douglas (1965). The Literary Background of the Gothic Revival in Germany - A chapter in the history of taste. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 504490694.

Stamp, Gavin (1995). C. Brooks, ed. The Victorian kirk: Presbyterian architecture in nineteenth century Scotland. The Victorian Church: Architecture and Society. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-4020-5.

Stanton, Phoebe B. (1997). The Gothic Revival and American Church Architecture: An Episode in Taste, 1840–1856. Baltimore, US and London: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801856228.

Steegman, John (1970). Victorian Taste - A study of the Arts and Architecture from 1830 to 1870. Cambridge: Nelson's University Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-2626-9028-7.

Turnor, Reginald (1950). Nineteenth Century Architecture in Britain. London: Batsford. OCLC 520344.

Тулешков, Николай (2007). Славинските първомайстори (in Bulgarian). София: Арх & Арт. ISBN 978-954-8931-40-3.

Whyte, Ian; Whyte, Kathleen A (1991). The Changing Scottish Landscape, 1500–1800. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415029926.

Further reading

- Christian Amalvi, Le Goût du moyen âge, (Paris: Plon), 1996. The first French monograph on French Gothic Revival.

"Le Gothique retrouvé" avant Viollet-le-Duc. Exhibition, 1979. The first French exhibition concerned with French Neo-Gothic.- Hunter-Stiebel, Penelope, Of knights and spires: Gothic revival in France and Germany, 1989. ISBN 0-614-14120-6

- Phoebe B Stanton, Pugin (New York, Viking Press 1972, ©1971). ISBN 0-670-58216-6

Summerson, Sir John, 1948. "Viollet-le-Duc and the rational point of view" collected in Heavenly Mansions and other essays on Architecture- Sir Thomas G. Jackson, Modern Gothic Architecture (1873), Byzantine and Romanesque Architecture (1913), and three-volume Gothic Architecture in France, England and Italy (1915)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gothic revival architecture. |

- Victoria and Albert Museum Style Guide

- Basilique Sainte-Clotilde, Paris

Canada by Design: Parliament Hill, Ottawa at Library and Archives Canada- Books, Research and Information

- Gothic Revival in Hamilton, Ontario Canada

- Proyecto Documenta's entries for neogothic elements at the Valparaíso's churches

- Toronto's Sanctuaries: Church Designs by Henry Langley

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP