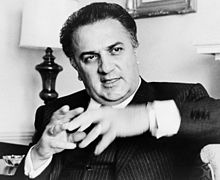

Federico Fellini

Federico Fellini OMRI | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | (1920-01-20)20 January 1920 Rimini, Italy |

| Died | 31 October 1993(1993-10-31) (aged 73) Rome, Italy |

| Cause of death | Heart attack |

| Occupation | Filmmaker |

| Years active | 1945–1992 |

| Notable work |

|

| Spouse(s) | Giulietta Masina (m. 1943) |

Federico Fellini, Cavaliere di Gran Croce OMRI (Italian: [fedeˈriːko felˈliːni]; 20 January 1920 – 31 October 1993) was an Italian film director and screenwriter. Known for his distinct style that blends fantasy and baroque images with earthiness, he is recognized as one of the greatest and most influential filmmakers of all time.[1][2][3] His films have ranked, in polls such as Cahiers du cinéma and Sight & Sound, as some of the greatest films of all time. Sight & Sound lists his 1963 film 8½ as the 10th-greatest film of all time.

In a career spanning almost fifty years, Fellini won the Palme d'Or for La Dolce Vita, was nominated for twelve Academy Awards, and directed four motion pictures that won Oscars in the category of Best Foreign Language Film. In 1993, he was awarded an honorary Oscar for Lifetime Achievement at the 65th Annual Academy Awards in Los Angeles.[4]

Besides La Dolce Vita and 8½, his other well-known films include La Strada, Nights of Cabiria, Juliet of the Spirits, Satyricon, Amarcord and Fellini's Casanova.

Contents

1 Early life and education

1.1 Rimini (1920–1938)

1.2 Rome (1939)

2 Career and later life

2.1 Early screenplays (1940–1943)

2.2 Neorealist apprenticeship (1944–1949)

2.3 Early films (1950–1953)

2.4 Beyond neorealism (1954–1960)

2.5 Art films and dreams (1961–1969)

2.6 Nostalgia, sexuality, and politics (1970–1980)

2.7 Late films and projects (1981–1990)

2.8 Final years (1991–1993)

3 Death

4 Religious views

5 Political views

6 Influence and legacy

7 Award and Nominations

7.1 Academy Awards

7.2 Selected awards and nominations

7.3 Distinctions

8 Filmography

8.1 As writer and director

8.2 Screenplay contributions

8.3 Television commercials

9 Documentaries on Fellini

10 See also

11 References

11.1 Notes

11.2 Bibliography

12 Further reading

13 External links

Early life and education

Rimini (1920–1938)

Fellini was born on 20 January 1920, to middle-class parents in Rimini, then a small town on the Adriatic Sea. His father, Urbano Fellini (1894–1956), born to a family of Romagnol peasants and small landholders from Gambettola, moved to Rome in 1915 as a baker apprenticed to the Pantanella pasta factory. His mother, Ida Barbiani (1896–1984), came from a bourgeiois Catholic family of Roman merchants. Despite her family's vehement disapproval, she had eloped with Urbano in 1917 to live at his parents' home in Gambettola.[5] A civil marriage followed in 1918 with the religious ceremony held at Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome a year later.

The couple settled in Rimini where Urbano became a traveling salesman and wholesale vendor. Fellini had two siblings: Riccardo (1921–1991), a documentary director for RAI Television, and Maria Maddalena (m. Fabbri; 1929–2002).

In 1924, Fellini started primary school in an institute run by the nuns of San Vincenzo in Rimini, attending the Carlo Tonni public school two years later. An attentive student, he spent his leisure time drawing, staging puppet shows, and reading Il corriere dei piccoli, the popular children’s magazine that reproduced traditional American cartoons by Winsor McCay, George McManus and Frederick Burr Opper. (Opper’s Happy Hooligan would provide the visual inspiration for Gelsomina in Fellini's 1954 film La Strada; McCay’s Little Nemo would directly influence his 1980 film City of Women.)[6] In 1926, he discovered the world of Grand Guignol, the circus with Pierino the Clown, and the movies. Guido Brignone’s Maciste all’Inferno (1926), the first film he saw, would mark him in ways linked to Dante and the cinema throughout his entire career.[7]

Enrolled at the Ginnasio Giulio Cesare in 1929, he made friends with Luigi ‘Titta’ Benzi, later a prominent Rimini lawyer (and the model for young Titta in Amarcord (1973)). In Mussolini’s Italy, Fellini and Riccardo became members of the Avanguardista, the compulsory Fascist youth group for males. He visited Rome with his parents for the first time in 1933, the year of the maiden voyage of the transatlantic ocean liner SS Rex (which is shown in Amarcord). The sea creature found on the beach at the end of La Dolce Vita (1960) has its basis in a giant fish marooned on a Rimini beach during a storm in 1934.

Although Fellini adapted key events from his childhood and adolescence in films such as I Vitelloni (1953), 8½ (1963), and Amarcord (1973), he insisted that such autobiographical memories were inventions:

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

It is not memory that dominates my films. To say that my films are autobiographical is an overly facile liquidation, a hasty classification. It seems to me that I have invented almost everything: childhood, character, nostalgias, dreams, memories, for the pleasure of being able to recount them.[8]

In 1937, Fellini opened Febo, a portrait shop in Rimini, with the painter Demos Bonini. His first humorous article appeared in the "Postcards to Our Readers" section of Milan’s Domenica del Corriere. Deciding on a career as a caricaturist and gag writer, Fellini travelled to Florence in 1938, where he published his first cartoon in the weekly 420. According to a biographer, Fellini found school "exasperating"[9] and, in one year, had 67 absences.[10] Failing his military culture exam, he graduated from high school in July 1938 after doubling the exam.

Rome (1939)

In September 1939, he enrolled in law school at the University of Rome to please his parents. Biographer Hollis Alpert reports that "there is no record of his ever having attended a class".[11] Installed in a family pensione, he met another lifelong friend, the painter Rinaldo Geleng. Desperately poor, they unsuccessfully joined forces to draw sketches of restaurant and café patrons. Fellini eventually found work as a cub reporter on the dailies Il Piccolo and Il Popolo di Roma, but quit after a short stint, bored by the local court news assignments.

Four months after publishing his first article in Marc’Aurelio, the highly influential biweekly humour magazine, he joined the editorial board, achieving success with a regular column titled But Are You Listening?[12] Described as “the determining moment in Fellini’s life”,[13] the magazine gave him steady employment between 1939 and 1942, when he interacted with writers, gagmen, and scriptwriters. These encounters eventually led to opportunities in show business and cinema. Among his collaborators on the magazine’s editorial board were the future director Ettore Scola, Marxist theorist and scriptwriter Cesare Zavattini, and Bernardino Zapponi, a future Fellini screenwriter. Conducting interviews for CineMagazzino also proved congenial: when asked to interview Aldo Fabrizi, Italy’s most popular variety performer, he established such immediate personal rapport with the man that they collaborated professionally. Specializing in humorous monologues, Fabrizi commissioned material from his young protégé.[14]

Career and later life

Early screenplays (1940–1943)

Federico Fellini during the 1950s

Retained on business in Rimini, Urbano sent wife and family to Rome in 1940 to share an apartment with his son. Fellini and Ruggero Maccari, also on the staff of Marc’Aurelio, began writing radio sketches and gags for films.

Not yet twenty and with Fabrizi’s help, Fellini obtained his first screen credit as a comedy writer on Mario Mattoli’s Il pirata sono io (The Pirate's Dream). Progressing rapidly to numerous collaborations on films at Cinecittà, his circle of professional acquaintances widened to include novelist Vitaliano Brancati and scriptwriter Piero Tellini. In the wake of Mussolini’s declaration of war against France and England on 10 June 1940, Fellini discovered Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, Gogol, John Steinbeck and William Faulkner along with French films by Marcel Carné, René Clair, and Julien Duvivier.[15] In 1941 he published Il mio amico Pasqualino, a 74-page booklet in ten chapters describing the absurd adventures of Pasqualino, an alter ego.[16]

Writing for radio while attempting to avoid the draft, Fellini met his future wife Giulietta Masina in a studio office at the Italian public radio broadcaster EIAR in the autumn of 1942. Well-paid as the voice of Pallina in Fellini's radio serial, Cico and Pallina, Masina was also well known for her musical-comedy broadcasts which cheered an audience depressed by the war.[17] In November 1942, Fellini was sent to Libya, occupied by Fascist Italy, to work on the screenplay of I cavalieri del deserto (Knights of the Desert, 1942), directed by Osvaldo Valenti and Gino Talamo. Fellini welcomed the assignment as it allowed him "to secure another extension on his draft order".[18] Responsible for emergency re-writing, he also directed the film's first scenes. When Tripoli fell under siege by British forces, he and his colleagues made a narrow escape by boarding a German military plane flying to Sicily. His African adventure, later published in Marc’Aurelio as "The First Flight", marked “the emergence of a new Fellini, no longer just a screenwriter, working and sketching at his desk, but a filmmaker out in the field”.[19]

The apolitical Fellini was finally freed of the draft when an Allied air raid over Bologna destroyed his medical records. Fellini and Giulietta hid in her aunt’s apartment until Mussolini's fall on 25 July 1943. After dating for nine months, the couple were married on 30 October 1943. Several months later, Masina fell down the stairs and suffered a miscarriage. She gave birth to a son, Pierfederico, on 22 March 1945, but the child died of encephalitis a month later on 24 April 1945.[20] The tragedy had enduring emotional and artistic repercussions.[21]

Neorealist apprenticeship (1944–1949)

After the Allied liberation of Rome on 4 June 1944, Fellini and Enrico De Seta opened the Funny Face Shop where they survived the postwar recession drawing caricatures of American soldiers. He became involved with Italian Neorealism when Roberto Rossellini, at work on Stories of Yesteryear (later Rome, Open City), met Fellini in his shop, and proposed he contribute gags and dialogue for the script. Aware of Fellini’s reputation as Aldo Fabrizi’s “creative muse”,[22] Rossellini also requested that he try to convince the actor to play the role of Father Giuseppe Morosini, the parish priest executed by the SS on 4 April 1944.

In 1947, Fellini and Sergio Amidei received an Oscar nomination for the screenplay of Rome, Open City.

Working as both screenwriter and assistant director on Rossellini’s Paisà (Paisan) in 1946, Fellini was entrusted to film the Sicilian scenes in Maiori. In February 1948, he was introduced to Marcello Mastroianni, then a young theatre actor appearing in a play with Giulietta Masina.[23] Establishing a close working relationship with Alberto Lattuada, Fellini co-wrote the director’s Senza pietà (Without Pity) and Il mulino del Po (The Mill on the Po). Fellini also worked with Rossellini on the anthology film L'Amore (1948), co-writing the screenplay and in one segment titled, "The Miracle", acting opposite Anna Magnani. To play the role of a vagabond rogue mistaken by Magnani for a saint, Fellini had to bleach his black hair blond.

Early films (1950–1953)

Fellini, Masina, Carla del Poggio and Alberto Lattuada, 1952

In 1950 Fellini co-produced and co-directed with Alberto Lattuada Variety Lights (Luci del varietà), his first feature film. A backstage comedy set among the world of small-time travelling performers, it featured Giulietta Masina and Lattuada’s wife, Carla del Poggio. Its release to poor reviews and limited distribution proved disastrous for all concerned. The production company went bankrupt, leaving both Fellini and Lattuada with debts to pay for over a decade.[24] In February 1950, Paisà received an Oscar nomination for the screenplay by Rossellini, Sergio Amidei, and Fellini.

After travelling to Paris for a script conference with Rossellini on Europa '51, Fellini began production on The White Sheik in September 1951, his first solo-directed feature. Starring Alberto Sordi in the title role, the film is a revised version of a treatment first written by Michelangelo Antonioni in 1949 and based on the fotoromanzi, the photographed cartoon strip romances popular in Italy at the time. Producer Carlo Ponti commissioned Fellini and Tullio Pinelli to write the script but Antonioni rejected the story they developed. With Ennio Flaiano, they re-worked the material into a light-hearted satire about newlywed couple Ivan and Wanda Cavalli (Leopoldo Trieste, Brunella Bovo) in Rome to visit the Pope. Ivan’s prissy mask of respectability is soon demolished by his wife’s obsession with the White Sheik. Highlighting the music of Nino Rota, the film was selected at Cannes (among the films in competition was Orson Welles’s Othello) and then retracted. Screened at the 13th Venice International Film Festival, it was razzed by critics in "the atmosphere of a soccer match”.[25] One reviewer declared that Fellini had “not the slightest aptitude for cinema direction".

In 1953, I Vitelloni found favour with the critics and public. Winning the Silver Lion Award in Venice, it secured Fellini his first international distributor.

Beyond neorealism (1954–1960)

Cinecittà - Teatro 5, Fellini's favorite studio[26]

Fellini directed La Strada based on a script completed in 1952 with Pinelli and Flaiano. During the last three weeks of shooting, Fellini experienced the first signs of severe clinical depression.[27] Aided by his wife, he undertook a brief period of therapy with Freudian psychoanalyst Emilio Servadio.[27]

Fellini cast American actor Broderick Crawford to interpret the role of an aging swindler in Il Bidone. Based partly on stories told to him by a petty thief during production of La Strada, Fellini developed the script into a con man’s slow descent towards a solitary death. To incarnate the role’s "intense, tragic face", Fellini’s first choice had been Humphrey Bogart[28] but after learning of the actor’s lung cancer, chose Crawford after seeing his face on the theatrical poster of All the King’s Men (1949). The film shoot was wrought with difficulties stemming from Crawford’s alcoholism.[29] Savaged by critics at the 16th Venice International Film Festival, the film did miserably at the box office and did not receive international distribution until 1964.

During the autumn, Fellini researched and developed a treatment based on a film adaptation of Mario Tobino’s novel, The Free Women of Magliano. Located in a mental institution for women, financial backers considered the subject had no potential and the project was abandoned.[citation needed]

While preparing Nights of Cabiria in spring 1956, Fellini learned of his father’s death by cardiac arrest at the age of sixty-two. Produced by Dino De Laurentiis and starring Giulietta Masina, the film took its inspiration from news reports of a woman’s severed head retrieved in a lake and stories by Wanda, a shantytown prostitute Fellini met on the set of Il Bidone.[30]Pier Paolo Pasolini was hired to translate Flaiano and Pinelli’s dialogue into Roman dialect and to supervise researches in the vice-afflicted suburbs of Rome. The movie won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film at the 30th Academy Awards and brought Masina the Best Actress Award at Cannes for her performance.[citation needed]

With Pinelli, he developed Journey with Anita for Sophia Loren and Gregory Peck. An "invention born out of intimate truth", the script was based on Fellini's return to Rimini with a mistress to attend his father's funeral.[31] Due to Loren’s unavailability, the project was shelved and resurrected twenty-five years later as Lovers and Liars (1981), a comedy directed by Mario Monicelli with Goldie Hawn and Giancarlo Giannini. For Eduardo De Filippo, he co-wrote the script of Fortunella, tailoring the lead role to accommodate Masina’s particular sensibility.[citation needed]

The Hollywood on the Tiber phenomenon of 1958 in which American studios profited from the cheap studio labour available in Rome provided the backdrop for photojournalists to steal shots of celebrities on the via Veneto.[32] The scandal provoked by Turkish dancer Haish Nana’s improvised striptease at a nightclub captured Fellini’s imagination: he decided to end his latest script-in-progress, Moraldo in the City, with an all-night "orgy" at a seaside villa. Pierluigi Praturlon’s photos of Anita Ekberg wading fully dressed in the Trevi Fountain provided further inspiration for Fellini and his scriptwriters.[citation needed]

Changing the title of the screenplay to La Dolce Vita, Fellini soon clashed with his producer on casting: the director insisted on the relatively unknown Mastroianni while De Laurentiis wanted Paul Newman as a hedge on his investment. Reaching an impasse, De Laurentiis sold the rights to publishing mogul Angelo Rizzoli. Shooting began on 16 March 1959 with Anita Ekberg climbing the stairs to the cupola of Saint Peter’s in a mammoth décor constructed at Cinecittà. The statue of Christ flown by helicopter over Rome to Saint Peter's Square was inspired by an actual media event on 1 May 1956, which Fellini had witnessed. The film wrapped August 15 on a deserted beach at Passo Oscuro with a bloated mutant fish designed by Piero Gherardi.[citation needed]

La Dolce Vita broke all box office records. Despite scalpers selling tickets at 1000 lire,[33] crowds queued in line for hours to see an “immoral movie” before the censors banned it. At an exclusive Milan screening on 5 February 1960, one outraged patron spat on Fellini while others hurled insults. Denounced in parliament by right-wing conservatives, undersecretary Domenico Magrì of the Christian Democrats demanded tolerance for the film’s controversial themes.[34] The Vatican's official press organ, l'Osservatore Romano, lobbied for censorship while the Board of Roman Parish Priests and the Genealogical Board of Italian Nobility attacked the film. In one documented instance involving favourable reviews written by the Jesuits of San Fedele, defending La Dolce Vita had severe consequences.[35] In competition at Cannes alongside Antonioni’s L’Avventura, the film won the Palme d'Or awarded by presiding juror Georges Simenon. The Belgian writer was promptly “hissed at” by the disapproving festival crowd.[36]

Art films and dreams (1961–1969)

Federico Fellini

A major discovery for Fellini after his Italian neorealism period (1950–1959) was the work of Carl Jung. After meeting Jungian psychoanalyst Dr. Ernst Bernhard in early 1960, he read Jung's autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections (1963) and experimented with LSD[37]. Bernhard also recommended that Fellini consult the I Ching and keep a record of his dreams. What Fellini formerly accepted as "his extrasensory perceptions"[38] were now interpreted as psychic manifestations of the unconscious. Bernhard’s focus on Jungian depth psychology proved to be the single greatest influence on Fellini’s mature style and marked the turning point in his work from neorealism to filmmaking that was "primarily oneiric".[39] As a consequence, Jung's seminal ideas on the anima and the animus, the role of archetypes and the collective unconscious directly influenced such films as 8½ (1963), Juliet of the Spirits (1965), Fellini Satyricon (1969), Casanova (1976), and City of Women (1980).[40] Other key influences on his work include Luis Buñuel,[41]Charlie Chaplin,[42]Sergei Eisenstein,[43]Buster Keaton,[44]Laurel and Hardy,[44] the Marx Brothers,[44] and Roberto Rossellini.[45]

Exploiting La Dolce Vita’s success, financier Angelo Rizzoli set up Federiz in 1960, an independent film company, for Fellini and production manager Clemente Fracassi to discover and produce new talent. Despite the best intentions, their overcautious editorial and business skills forced the company to close down soon after cancelling Pasolini’s project, Accattone (1961).[46]

Condemned as a "public sinner"[47] for La Dolce Vita, Fellini responded with The Temptations of Doctor Antonio, a segment in the omnibus Boccaccio '70. His second colour film, it was the sole project green-lighted at Federiz. Infused with the surrealistic satire that characterized the young Fellini’s work at Marc’Aurelio, the film ridiculed a crusader against vice, interpreted by Peppino De Filippo, who goes insane trying to censor a billboard of Anita Ekberg espousing the virtues of milk.[citation needed]

In an October 1960 letter to his colleague Brunello Rondi, Fellini first outlined his film ideas about a man suffering creative block: "Well then - a guy (a writer? any kind of professional man? a theatrical producer?) has to interrupt the usual rhythm of his life for two weeks because of a not-too-serious disease. It’s a warning bell: something is blocking up his system."[48] Unclear about the script, its title, and his protagonist’s profession, he scouted locations throughout Italy “looking for the film”[49] in the hope of resolving his confusion. Flaiano suggested La bella confusione (literally The Beautiful Confusion) as the movie’s title. Under pressure from his producers, Fellini finally settled on 8½, a self-referential title referring principally (but not exclusively)[50] to the number of films he had directed up to that time.

Giving the order to start production in spring 1962, Fellini signed deals with his producer Rizzoli, fixed dates, had sets constructed, cast Mastroianni, Anouk Aimée, and Sandra Milo in lead roles, and did screen tests at the Scalera Studios in Rome. He hired cinematographer Gianni Di Venanzo, among key personnel. But apart from naming his hero Guido Anselmi, he still couldn't decide what his character did for a living.[51] The crisis came to a head in April when, sitting in his Cinecittà office, he began a letter to Rizzoli confessing he had "lost his film" and had to abandon the project. Interrupted by the chief machinist requesting he celebrate the launch of 8½, Fellini put aside the letter and went on the set. Raising a toast to the crew, he "felt overwhelmed by shame… I was in a no exit situation. I was a director who wanted to make a film he no longer remembers. And lo and behold, at that very moment everything fell into place. I got straight to the heart of the film. I would narrate everything that had been happening to me. I would make a film telling the story of a director who no longer knows what film he wanted to make".[52]

Shooting began on 9 May 1962. Perplexed by the seemingly chaotic, incessant improvisation on the set, Deena Boyer, the director’s American press officer at the time, asked for a rationale. Fellini told her that he hoped to convey the three levels "on which our minds live: the past, the present, and the conditional - the realm of fantasy".[53] After shooting wrapped on 14 October, Nino Rota composed various circus marches and fanfares that would later become signature tunes of the maestro’s cinema.[54] Nominated for four Oscars, 8½ won awards for best foreign language film and best costume design in black-and-white. In California for the ceremony, Fellini toured Disneyland with Walt Disney the day after.

Increasingly attracted to parapsychology, Fellini met the Turin magician Gustavo Rol in 1963. Rol, a former banker, introduced him to the world of Spiritism and séances. In 1964, Fellini took LSD[55] under the supervision of Emilio Servadio, his psychoanalyst during the 1954 production of La Strada.[56] For years reserved about what actually occurred that Sunday afternoon, he admitted in 1992 that

objects and their functions no longer had any significance. All I perceived was perception itself, the hell of forms and figures devoid of human emotion and detached from the reality of my unreal environment. I was an instrument in a virtual world that constantly renewed its own meaningless image in a living world that was itself perceived outside of nature. And since the appearance of things was no longer definitive but limitless, this paradisiacal awareness freed me from the reality external to my self. The fire and the rose, as it were, became one.[57]

Fellini's hallucinatory insights were given full flower in his first colour feature Juliet of the Spirits (1965), depicting Giulietta Masina as Juliet, a housewife who rightly suspects her husband's infidelity and succumbs to the voices of spirits summoned during a séance at her home. Her sexually voracious next door neighbor Suzy (Sandra Milo) introduces Juliet to a world of uninhibited sensuality but Juliet is haunted by childhood memories of her Catholic guilt and a teenaged friend who committed suicide. Complex and filled with psychological symbolism, the film is set to a jaunty score by Nino Rota.

Nostalgia, sexuality, and politics (1970–1980)

Fellini & Bruno Zanin on the set of Amarcord in 1973

To help promote Satyricon in the United States, Fellini flew to Los Angeles in January 1970 for interviews with Dick Cavett and David Frost. He also met with film director Paul Mazursky who wanted to star him alongside Donald Sutherland in his new film, Alex in Wonderland.[58] In February, Fellini scouted locations in Paris for The Clowns, a docufiction both for cinema and television, based on his childhood memories of the circus and a "coherent theory of clowning."[59] As he saw it, the clown "was always the caricature of a well-established, ordered, peaceful society. But today all is temporary, disordered, grotesque. Who can still laugh at clowns?... All the world plays a clown now."[60]

In March 1971, Fellini began production on Roma, a seemingly random collection of episodes informed by the director's memories and impressions of Rome. The "diverse sequences," writes Fellini scholar Peter Bondanella, "are held together only by the fact that they all ultimately originate from the director’s fertile imagination."[61] The film’s opening scene anticipates Amarcord while its most surreal sequence involves an ecclesiastical fashion show in which nuns and priests roller skate past shipwrecks of cobwebbed skeletons.

Over a period of six months between January and June 1973, Fellini shot the Oscar-winning Amarcord. Loosely based on the director’s 1968 autobiographical essay My Rimini,[62] the film depicts the adolescent Titta and his friends working out their sexual frustrations against the religious and Fascist backdrop of a provincial town in Italy during the 1930s. Produced by Franco Cristaldi, the seriocomic movie became Fellini’s second biggest commercial success after La Dolce Vita.[63] Circular in form, Amarcord avoids plot and linear narrative in a way similar to The Clowns and Roma.[64] The director's overriding concern with developing a poetic form of cinema was first outlined in a 1965 interview he gave to The New Yorker journalist Lillian Ross: "I am trying to free my work from certain constrictions – a story with a beginning, a development, an ending. It should be more like a poem with metre and cadence."[65]

Late films and projects (1981–1990)

Italian President Sandro Pertini receiving a David di Donatello Award from Fellini in 1985

Organized by his publisher Diogenes Verlag in 1982, the first major exhibition of 63 drawings by Fellini was held in Paris, Brussels, and the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York.[66] A gifted caricaturist, much of the inspiration for his sketches was derived from his own dreams while the films-in-progress both originated from and stimulated drawings for characters, decor, costumes and set designs. Under the title, I disegni di Fellini (Fellini’s Designs), he published 350 drawings executed in pencil, watercolours, and felt pens.[67]

On 6 September 1985 Fellini was awarded the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement at the 42nd Venice Film Festival. That same year, he became the first non-American to receive the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s annual award for cinematic achievement.[citation needed]

Long fascinated by Carlos Castaneda’s The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge, Fellini accompanied the Peruvian author on a journey to the Yucatán to assess the feasibility of a film. After first meeting Castaneda in Rome in October 1984, Fellini drafted a treatment with Pinelli titled Viaggio a Tulun. Producer Alberto Grimaldi, prepared to buy film rights to all of Castaneda’s work, then paid for pre-production research taking Fellini and his entourage from Rome to Los Angeles and the jungles of Mexico in October 1985.[68] When Castaneda inexplicably disappeared and the project fell through, Fellini’s mystico-shamanic adventures were scripted with Pinelli and serialized in Corriere della Sera in May 1986. A barely veiled satirical interpretation of Castaneda's work,[69]Viaggio a Tulun was published in 1989 as a graphic novel with artwork by Milo Manara and as Trip to Tulum in America in 1990.

For Intervista, produced by Ibrahim Moussa and RAI Television, Fellini intercut memories of the first time he visited Cinecittà in 1939 with present-day footage of himself at work on a screen adaptation of Franz Kafka’s Amerika. A meditation on the nature of memory and film production, it won the special 40th Anniversary Prize at Cannes and the 15th Moscow International Film Festival Golden Prize. In Brussels later that year, a panel of thirty professionals from eighteen European countries named Fellini the world’s best director and 8½ the best European film of all time.[70]

In early 1989 Fellini began production on The Voice of the Moon, based on Ermanno Cavazzoni’s novel, Il poema dei lunatici (The Lunatics' Poem). A small town was built at Empire Studios on the via Pontina outside Rome. Starring Roberto Benigni as Ivo Salvini, a madcap poetic figure newly released from a mental institution, the character is a combination of La Strada's Gelsomina, Pinocchio, and Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi.[71] Fellini improvised as he filmed, using as a guide a rough treatment written with Pinelli.[72] Despite its modest critical and commercial success in Italy, and its warm reception by French critics, it failed to interest North American distributors.[citation needed]

Fellini won the Praemium Imperiale, the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in the visual arts, awarded by the Japan Art Association in 1990.[73]

Final years (1991–1993)

In July 1991 and April 1992, Fellini worked in close collaboration with Canadian filmmaker Damian Pettigrew to establish "the longest and most detailed conversations ever recorded on film".[74] Described as the "Maestro's spiritual testament” by his biographer Tullio Kezich,[75] excerpts culled from the conversations later served as the basis of their feature documentary, Fellini: I'm a Born Liar (2002) and the book, I'm a Born Liar: A Fellini Lexicon. Finding it increasingly difficult to secure financing for feature films, Fellini developed a suite of television projects whose titles reflect their subjects: Attore, Napoli, L’Inferno, L'opera lirica, and L’America.[citation needed]

In April 1993 Fellini received his fifth Oscar, for lifetime achievement, "in recognition of his cinematic accomplishments that have thrilled and entertained audiences worldwide". On 16 June, he entered the Cantonal Hospital in Zurich for an angioplasty on his femoral artery[76] but suffered a stroke at the Grand Hotel in Rimini two months later. Partially paralyzed, he was first transferred to Ferrara for rehabilitation and then to the Policlinico Umberto I in Rome to be near his wife, also hospitalized. He suffered a second stroke and fell into an irreversible coma.[77]

Death

Fellini died in Rome on 31 October 1993 at the age of 73 after a heart attack he suffered a few weeks earlier,[78] a day after his fiftieth wedding anniversary. The memorial service was held in Studio 5 at Cinecittà attended by an estimated 70,000 people.[79] At the request of Giulietta Masina, trumpeter Mauro Maur played the "Improvviso dell'Angelo" by Nino Rota during the funeral ceremony.[80]

Five months later, on 23 March 1994, Fellini's widow, actress Giulietta Masina died of lung cancer. Fellini, Masina and their son, Pierfederico, are buried in a bronze sepulchre sculpted by Arnaldo Pomodoro. Designed as a ship's prow, the tomb is located at the main entrance to the Cemetery of Rimini. The Federico Fellini Airport in Rimini is named in his honour.[citation needed]

Religious views

Fellini was raised in a Roman Catholic family, and considered himself a Catholic, although, as an adult, he avoided formal activity in the Catholic Church. Films by Fellini included Catholic themes: some celebrated Catholic teachings; whereas others were critical or ridiculed church dogma.[81]

Political views

While Fellini was for the most part indifferent to politics,[82] he had a general dislike of authoritarian institutions, and is interpreted by Bondanella as believing in "the dignity and even the nobility of the individual human being".[83] In a 1966 interview, he stated, "I make it a point to see if certain ideologies or political attitudes threaten the private freedom of the individual. But for the rest, I am not prepared nor do I plan to become interested in politics."[84] Despite various famous Italian actors favouring the Communists, Fellini was not left-wing as it is rumored that he supported Christian Democracy (DC).[85]

Although Bondanella reports that the Christian Democratic party "was far too aligned with an extremely conservative and even reactionary pre-Vatican II church to suit Fellini's tastes."[83] The director still opposed the '68 Movement, and befriended Giulio Andreotti.[86]

Apart from satirizing Silvio Berlusconi and mainstream television in Ginger and Fred,[87] Fellini rarely expressed his political views in public and never directed an overtly political film. He directed two electoral television spots during the 1990s: one for DC and another for the Italian Republican Party or PRI.[88] His slogan, "Non si interrompe un'emozione" (Don't interrupt an emotion), was directed against the excessive use of advertisements in TV. The slogan was also used by the Democratic Party of the Left in the referendums of 1995.[citation needed]

Influence and legacy

Dedicatory plaque to Fellini on Via Veneto, Rome:

To Federico Fellini, who made Via Veneto the stage for the "Sweet Life" - SPQR - January 20, 1995

Personal and highly idiosyncratic visions of society, Fellini's films are a unique combination of memory, dreams, fantasy and desire. The adjectives "Fellinian" and "Felliniesque" are "synonymous with any kind of extravagant, fanciful, even baroque image in the cinema and in art in general".[6]La Dolce Vita contributed the term paparazzi to the English language, derived from Paparazzo, the photographer friend of journalist Marcello Rubini (Marcello Mastroianni).[89]

Contemporary filmmakers such as Tim Burton,[90]Terry Gilliam,[91]Emir Kusturica,[92] and David Lynch,[93] have cited Fellini's influence on their work.

Polish director Wojciech Has, whose two best-received films, The Saragossa Manuscript (1965) and The Hour-Glass Sanatorium (1973), are examples of modernist fantasies, has been compared to Fellini for the sheer "luxuriance of his images".[94]

I Vitelloni inspired European directors Juan Antonio Bardem, Marco Ferreri, and Lina Wertmüller and had an influence on Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets (1973), George Lucas's American Graffiti (1974), Joel Schumacher's St. Elmo's Fire (1985), and Barry Levinson's Diner (1987), among many others.[95] When the American magazine Cinema asked Stanley Kubrick in 1963 to name his favorite films, the film director listed I Vitelloni as number one in his Top 10 list.[96]

Nights of Cabiria was adapted as the Broadway musical Sweet Charity and the movie Sweet Charity (1969) by Bob Fosse starring Shirley MacLaine. City of Women was adapted for the Berlin stage by Frank Castorf in 1992.[citation needed]

8½ inspired among others: Mickey One (Arthur Penn, 1965), Alex in Wonderland (Paul Mazursky, 1970), Beware of a Holy Whore (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1971), Day for Night (François Truffaut, 1973), All That Jazz (Bob Fosse, 1979), Stardust Memories (Woody Allen, 1980), Sogni d'oro (Nanni Moretti, 1981), Parad Planet (Vadim Abdrashitov, 1984), La Pelicula del rey (Carlos Sorin, 1986), Living in Oblivion (Tom DiCillo, 1995), 8½ Women (Peter Greenaway, 1999), Falling Down (Joel Schumacher, 1993), along with the successful Broadway musical, Nine (Maury Yeston and Arthur Kopit, 1982).[97]Yo-Yo Boing! (1998), a Spanish novel by Puerto Rican writer Giannina Braschi, features a dream sequence with Fellini that was inspired by 8½.[98]

Fellini’s work is referenced on the albums Fellini Days (2001) by Fish, Another Side of Bob Dylan (1964) by Bob Dylan with Motorpsycho Nitemare, Funplex (2008) by the B-52's with the song Juliet of the Spirits, and in the opening traffic jam of the music video Everybody Hurts by R.E.M.[99] American singer Lana Del Rey has cited Fellini as an influence.[100] It influenced two American TV shows, Northern Exposure and Third Rock from the Sun.[101]Wes Anderson's short film Castello Cavalcanti (2013) is in many places a direct homage to Fellini's work.[102]

Various film related material and personal papers of Fellini are contained in the Wesleyan University Cinema Archives to which scholars and media experts from around the world may have full access.[103] In October 2009, the Jeu de Paume in Paris opened an exhibit devoted to Fellini that included ephemera, television interviews, behind-the-scenes photographs, Book of Dreams (based on 30 years of the director's illustrated dreams and notes), along with excerpts from La dolce vita and 8½.[104]

In 2014, the Blue Devils Drum and Bugle Corps of Concord, California performed a show themed around Fellini's works, entitled "Felliniesque", with which the Blue Devils won a record 16th Drum Corps International World Class championship with a record score of 99.650.[105] That same year, the weekly entertainment-trade magazine Variety announced that French director Sylvain Chomet was moving forward with the project, The Thousand Miles, based on various works of Fellini including his unpublished drawings and writings.[106]

Award and Nominations

Academy Awards

| Year | Film | Category | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

1946 | Rome, Open City | Best Original Screenplay | Nominated Shared with Sergio Amidei |

1949 | Paisan | Best Original Screenplay | Nominated Shared with V. Hayes, Sergio Amidei, Marcello Pagliero, and Roberto Rossellini |

1956 | La Strada | Best Foreign Language Film | Won |

| 1956 | La Strada | Best Original Screenplay | Nominated Shared with Tullio Pinelli |

1957 | Nights of Cabiria | Best Foreign Language Film | Won |

| 1957 | I Vitelloni | Best Original Screenplay | Nominated Shared with Ennio Flaiano and Tullio Pinelli |

1961 | La Dolce Vita | Best Original Screenplay | Nominated Shared with Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli and Brunello Rondi |

1963 | 8½ | Best Foreign Language Film | Won |

| 1963 | 8½ | Best Original Screenplay | Nominated Shared with Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli and Brunello Rondi |

1974 | Amarcord | Best Foreign Language Film | Won |

| 1974 | Amarcord | Best Original Screenplay | Nominated Shared with Tonino Guerra |

1976 | Fellini's Casanova | Best Adapted Screenplay | Nominated Shared with Bernardino Zapponi |

1992 | Himself | Academy Honorary Award | Won |

Selected awards and nominations

Rome, Open City (Dir. Roberto Rossellini, 1945)

Oscar nomination for Best Screenplay (with Sergio Amidei)

Paisà (Dir. Roberto Rossellini, 1946)

Oscar nomination for Best Screenplay (with Sergio Amidei, Alfred Hayes, Marcello Pagliero, and Rossellini)

I Vitelloni (1953)- Venice Film Festival Silver Lion

Oscar nomination for Best Screenplay (with Tullio Pinelli, Ennio Flaiano)

- Venice Film Festival Silver Lion

La Strada (1954)- Venice Film Festival Silver Lion

Oscar for the Best Foreign Language Film[107]

Oscar nomination for Best Screenplay (with Tullio Pinelli, Ennio Flaiano)

New York Film Critics Award for Best Foreign Film

Screen Directors Guild Award for Best Foreign Film

- Venice Film Festival Silver Lion

Nights of Cabiria (1957)

Festival de Cannes Best Actress Award (Giulietta Masina)[108]

Oscar for the Best Foreign Language Film[109]

La Dolce Vita (1960)

Palme d'Or at Festival de Cannes

Oscar Best Costumes in B&W (Piero Gherardi)

Oscar nominations for Best Director, Best Screenplay (with Tullio Pinelli, Ennio Flaiano, Brunello Rondi), Best Art and Set Direction- New York Film Critics Award for Best Foreign Language Film

National Board of Review citation for Best Foreign Language Film

8½ (Otto e Mezzo, 1963)

Moscow International Film Festival Grand Prize[110]

Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film[111]

Oscar for Best Costumes in B&W (Piero Gherardi)

Oscar nomination for Best Director

Oscar nomination for Best Art Direction-Set Decoration in B&W (Piero Gherardi)

Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists Silver Ribbons for Best Cinematography in B&W (Gianni Di Venanzo), Best Director (Federico Fellini), Best Original Story (Fellini and Flaiano), Best Producer (Angelo Rizzoli), Best Score (Nino Rota), Best Screenplay (Fellini, Pinelli, Flaiano, Rondi), and Best Supporting Actress (Sandra Milo)

Berlin International Film Festival Special Award

BAFTA Film Award nomination for Best Film from any Source

Bodil Award for Best European Film

Directors Guild of America Award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures- New York Film Critics Award for Best Foreign Film

- National Board of Review Award for Best Foreign Language Picture

- Grolla d’Oro at Saint Vincent Film Festival for Best Director

Kinema Junpo Award for Best Foreign Language Film & Best Foreign Language Film Director

Juliet of the Spirits (1965)- New York Film Critics Award for Best Foreign Film

- National Board of Review Award for Best Foreign Language Story

Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film

Fellini Satyricon (1969)

Oscar nomination for Best Director[112]

I clowns (1970)- National Board of Review citation for Best Foreign Language Film

Amarcord (1974)

Oscar for Best Foreign Film[113]

Oscar nomination for Best Director

Oscar nomination for Best Writing, Original Screenplay- New York Film Critics Award for Best Direction

- New York Film Critics Award for Best Motion Picture

Fellini's Casanova (1976)

Oscar for Best Costumes (Danilo Donati)

Intervista (1987)

15th Moscow International Film Festival Golden Prize[114]

Festival de Cannes Special 40th Anniversary Prize

The Voice of the Moon (1990)- David di Donatello Awards for Best Actor, Best Production Design, and Best Editing

Distinctions

1964

Grande Ufficiale OMRI[115]

1974- 27th Cannes Film Festival Lifetime Achievement Award (with French director René Clair)

1985- 42nd Venice Film Festival Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement

Film Society of Lincoln Center Award for Cinematic Achievement

1987

Cavaliere di Gran Croce OMRI[116]

1989- Lifetime Achievement Award - European Film Awards

- Lifetime Achievement Award - European Film Awards

1990- Japan Art Association's Praemium Imperiale (equivalent of the Nobel Prize in the visual arts)

1993

Oscar for Lifetime Achievement

Filmography

As writer and director

Luci del varietà (1950) (co-credited with Alberto Lattuada)

Lo sceicco bianco (1952)

I vitelloni (1953)

L'amore in città (1953) (segment Un'agenzia matrimoniale)

La strada (1954)

Il bidone (1955)

Le notti di Cabiria (1957)

La Dolce Vita (1960)

Boccaccio '70 (1962) (segment Le tentazioni del Dottor Antonio)

8½ (1963)

Giulietta degli spiriti (1965)

Histoires extraordinaires (1968) (segment Toby Dammit, based on Edgar Allan Poe's short story "Never Bet the Devil Your Head")

Fellini: A Director's Notebook (1969)

Fellini Satyricon (1969)

I clowns (1970)

Roma (1972)

Amarcord (1973)

Il Casanova di Federico Fellini (1976)

Prova d'orchestra (1978)

La città delle donne (1980)

E la nave va (1983)

Ginger e Fred (1986)

Intervista (1987)

La voce della luna (1990)

Screenplay contributions

Knights of the Desert (1942)

Before the Postman (1942)

The Peddler and the Lady (1943)

L'ultima carrozzella (1943) (dir. Mario Mattoli) Co-scriptwriter

Roma, città aperta (1945) (dir. Roberto Rossellini) Co-scriptwriter

Paisà (1946) (dir. Roberto Rossellini). Co-scriptwriter

Black Eagle (1946) (dir. Riccardo Freda) Co-scriptwriter

Il delitto di Giovanni Episcopo (1947) (dir. Alberto Lattuada) Co-scriptwriter

Senza pietà (1948) (dir. Alberto Lattuada) Co-scriptwriter

Il miracolo (1948) (dir. Roberto Rossellini) Co-scriptwriter

Il mulino del Po (1949) (dir. Alberto Lattuada) Co-scriptwriter

Francesco, giullare di Dio (1950) (dir. Roberto Rossellini) Co-scriptwriter

Il Cammino della speranza (1950) (dir. Pietro Germi) Co-scriptwriter

La città si difende (1951) (dir. Pietro Germi) Co-scriptwriter

Persiane chiuse (1951) (dir. Luigi Comencini) Co-scriptwriter

Il brigante di Tacca del Lupo (1952) (dir. Pietro Germi) Co-scriptwriter

Fortunella (1979) (dir. Eduardo De Filippo) Co-scriptwriter

Lovers and Liars (1979) (dir. Mario Monicelli) Fellini not credited

Television commercials

- TV commercial for Campari Soda (1984)

- TV commercial for Barilla pasta (1984)

- Three TV commercials for Banca di Roma (1992)

Documentaries on Fellini

Ciao Federico (1969). Dir. Gideon Bachmann. (60')

Federico Fellini - un autoritratto ritrovato (2000). Dir. Paquito Del Bosco. (RAI TV, 68')

Fellini: I'm a Born Liar (2002). Dir. Damian Pettigrew. Feature documentary. (ARTE, Eurimages, Scottish Screen, 102')

How Strange to Be Named Federico (2013). Dir. Ettore Scola.

See also

- Art film

References

Notes

^ "The 25 Most Influential Directors of All Time". MovieMaker Magazine.

^ "10 Most Influential Directors Of All Time". WhatCulture.com.

^ Burke and Waller, 12

^ "Federico Fellini".

^ Alpert, 16

^ ab Bondanella, The Films of Federico Fellini, 7

^ Burke and Waller, 5–13

^ Fellini interview in Panorama 18 (14 January 1980). Screenwriters Tullio Pinelli and Bernardino Zapponi, cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno and set designer Dante Ferretti also reported that Fellini imagined many of his “memories”. Cf. Bernardino Zapponi's memoir, Il mio Fellini and Fellini's own insistence on having created his cinematic autobiography in I'm a Born Liar: A Fellini Lexicon, 32

^ Kezich, 17

^ Kezich, 14

^ Alpert, 33

^ Kezich, 31

^ Bondanella, The Films of Federico Fellini, 8

^ Kezich, 55

^ Alpert, 42

^ Kezich, 35

^ "Giulietta is practical, and likes the fact that she earns a handsome fee for her radio work, whereas theater never pays well. And of course the fame counts for something too. Radio is a booming business and comedy reviews have a broad and devoted public." Kezich, 48

^ Kezich, 70

^ Kezich, 71

^ Kezich, 74

^ Kezich, 157. Cf. filmed interview with Luigi 'Titta' Benzi in Fellini: I'm a Born Liar (2003).

^ Kezich, 78

^ Kezich, 404

^ Kezich, 114

^ Kezich, 128

^ "Our flexible giant". Cinecittà Studios. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

^ ab Kezich, 158

^ Kezich, p. 167

^ Kezich, pp. 168-69

^ Kezich, p. 177

^ Kezich, 189

^ Alpert, 122

^ Kezich, 208

^ Kezich, p. 209

^ Kezich, p. 210

^ Alpert, p. 145

^ "FELLINI E L' LSD - sostanze.info". www.sostanze.info.

^ Kezich, p. 224

^ Kezich, p. 227

^ Bondanella, Cinema of Federico Fellini, pp. 151-54

^ "Buñuel is the auteur I feel closest to in terms of an idea of cinema or the tendency to make particular kinds of films." In Fellini and Pettigrew, I’m a Born Liar: A Fellini Lexicon, 87.

^ “One of Cabiria’s finest moments comes in the movie’s nightclub scene. It begins when the actor’s girlfriend deserts him, and the star picks up Cabiria on the street as a replacement. He whisks her away to the nightclub. Fellini has admitted that this scene owes a debt to Chaplin’s City Lights (1931)." Cited in John C. Stubbs, Federico Fellini as Auteur: Seven Aspects of his Films (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2006), pp. 152-53. Peter Bondanella points out that Gelsomina's costume, makeup, and antics as a clown figure had "clear links to Fellini's past as a cartoonist-imitator of Happy Hooligan and Charlie Chaplin". Cited in Bondanella, The Cinema of Federico Fellini, 104

^ In his study of Fellini Satyricon, Italian novelist Alberto Moravia observes that with "the oars of his galleys suspended in the air, Fellini revives for us the lances of the battle in Eisenstein's Alexander Nevsky (film)." Cited in Bondanella (ed), Federico Fellini: Essays in Criticism, 167

^ abc Bondanella, The Cinema of Federico Fellini, 8

^ “Roberto Rossellini walked into my life at a moment when I needed to make a choice, when I needed someone to show me the path to follow. He was the stationmaster, the green light of providence... He taught me how to thrive on chaos by ignoring it and focusing on what was essential: constructing your film day by day.” Cited in Federico Fellini and Damian Pettigrew, pp. 17-18. In Fellini on Fellini, the director explains that his "meeting with Rossellini was a determining factor... he taught me to make a film as if I were going for a picnic with friends." In Fellini on Fellini (London: Eyre Methuen, 1976), 99-100

^ Kezich, pp. 218-219

^ Kezich, 212

^ Affron, 227

^ Alpert, 159

^ Kezich, p. 234 and Affron, pp. 3-4

^ Alpert, p. 160

^ Fellini, Comments on Film, pp. 161-62

^ Alpert, 170

^ Kezich, 245

^ A synthetic derivative "fashioned to produce the same effects as the hallucinogenic mushrooms used by Mexican tribes". Kezich, 255

^ Kezich, 255

^ Fellini and Pettigrew, p. 91

^ Kezich, 410

^ Bondanella, The Cinema of Federico Fellini, 192

^ Alpert, p. 224

^ Bondanella, The Cinema of Federico Fellini, 193

^ Alpert, 239

^ Bondanella, The Cinema of Federico Fellini, p. 265

^ Alpert, p. 242

^ Bondanella, Federico Fellini: Essays in Criticism, p. 104

^ Kezich, 413. Also cf. The Warsaw Voice[permanent dead link]

^ Fellini, I disegni di Fellini (Roma: Editori Laterza), 1993. The drawings are edited and analysed by Pier Marco De Santi. For comparing Fellini's graphic work with those of Sergei Eisenstein, consult S.M. Eisenstein, Dessins secrets (Paris: Seuil), 1999.

^ Kezich, 360-61

^ Kezich, 362

^ Burke and Waller, p. xvi

^ Bondanella, Cinema of Federico Fellini, p. 330

^ Kezich, 383

^ Kezich, p. 387. The award covers five disciplines: painting, sculpture, architecture, music, and theatre/film. Other winners include Akira Kurosawa, David Hockney, Balthus, Pina Bausch, and Maurice Béjart.

^ Peter Bondanella, Review of Fellini: I'm a Born Liar in Cineaste Magazine (22 September 2003), p. 32

^ Kezich, "Forward" in I'm a Born Liar: A Fellini Lexicon, 5. Also cf. Kezich, p. 388

^ Kezich, p. 396

^ "Federico Fellini, Film Visionary, Is Dead at 73". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

^ Federico Fellini, Film Visionary, Is Dead at 73, nytimes.com; accessed 28 August 2017.

^ Kezich, 416

^ "fellini funerali - Basilica di Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri alle Terme di Diocleziano di Roma". santamariadegliangeliroma.it (in Italian).

^ Staff (2 September 2005). "The Religious Affiliation of Director Federico Fellini". Adherents.com. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

^ Kezich, 45

^ ab Bondanella, The Films of Federico Fellini, p. 119

^ Cardullo, Bert, ed. (2006). Federico Fellini: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 63. ISBN 1578068851.

^ Franco Bianchini (31 October 2013). "Il Fellini che non vi raccontano: votava Dc, rifiutava il cinema impegnato ed era contro il '68". Secolo d'Italia (in Italian).

^ Jacopo Iacoboni (28 March 2012). "Caro Andreotti, caro Fellini l'amicizia tra due arcitaliani". La Stampa (in Italian).

^ Kezich, 367

^ "Con DC e PRI, Federico Fellini sponsor di due nemicicon DC e PRI, Federico Fellini sponsor di due nemici". il Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 18 March 1992.

^ Ennio Flaiano, the film's co-screenwriter and creator of Paparazzo, explained that he took the name from Signor Paparazzo, a character in George Gissing's novel By the Ionian Sea (1901). Bondanella, The Cinema of Federico Fellini, p. 136

^ Tim Burton Collective Archived June 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

^ Gilliam at Senses of Cinema Archived 2010-02-09 at the Wayback Machine.; accessed 17 September 2008.

^ Kusturica Interview at BNET; accessed 17 September 2008.

^ City of Absurdity Quote Collection; accessed 17 September 2008.

^ Gilbert Guez, review of The Saragossa Manuscript in Le Figaro, September 1966, p. 23

^ Kezich, 137

^ Ciment, Michel. "Kubrick: Biographical Notes"; accessed 23 December 2009.

^ Numerous sources include Affron, Alpert, Bondanella, Kezich, Miller et al.

^ Introduction to Giannina Braschi's Yo-Yo Boing!, Doris Sommer, Harvard University, Latin American Literary Review Press, 1998.

^ Miller, 7

^ Sciarretto, Amy (20 January 2015). "Lana Del Rey Is Working on New Music and Shared Some Hints About It". Artistdirect. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

^ Burke and Waller, p. xv

^ "Wes Anderson Honors Fellini in a Delightful New Short Film". Slate. 12 November 2013. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

^ "Cinema Archives - Wesleyan University". wesleyan.edu.

^ Baker, Tamzin. "Federico Fellini", Modern Painters, November 2009.

^ "2014 DCI Champions", Halftime Magazine, Sept/Oct 2014.

^ "Sylvain Chomet Steps Up for The Thousand Miles, Variety.com; accessed 28 August 2017.

^ "The 29th Academy Awards (1957) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

^ "Festival de Cannes: Nights of Cabiria". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

^ "The 30th Academy Awards (1958) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

^ "3rd Moscow International Film Festival (1963)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

^ "The 36th Academy Awards (1964) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

^ "The 43rd Academy Awards (1971) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

^ "The 47th Academy Awards (1975) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

^ "15th Moscow International Film Festival (1987)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

^ web, Segretariato generale della Presidenza della Repubblica-Servizio sistemi informatici- reparto. "Le onorificenze della Repubblica Italiana". quirinale.it. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

^ "Le onorificenze della Repubblica Italiana". Retrieved 28 August 2017.|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help)

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Fellini, Federico (1988). Comments on Film. Ed. Giovanni Grazzini. Trans. Joseph Henry. Fresno: The Press of California State University at Fresno.

- — (1993). I disegni di Fellini. Ed. Pier Marco De Santi. Roma: Editori Laterza.

- — and Damian Pettigrew (2003). I'm a Born Liar: A Fellini Lexicon. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8478-3135-3

- — and Tullio Pinelli. Trip to Tulum. Trans. Stefano Gaudiano and Elizabeth Bell. New York: Catalan Communications.

- — (2015). Making a Film. Trans. Christopher Burton White. Autobiographical Essay by Italo Calvino. New York: Contra Mundum Press.

Secondary sources

Alpert, Hollis (1988). Fellini: A Life. New York: Paragon House. ISBN 1-55778-000-5- Bondanella, Peter (ed.)(1978). Federico Fellini: Essays in Criticism. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-502274-2

- — (1992). The Cinema of Federico Fellini. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00875-2

- — (2002). The Films of Federico Fellini. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN 9780521575737.

- Burke, Frank, and M. R. Waller (2003). Federico Fellini: Contemporary Perspectives. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-7647-5

Kezich, Tullio (2006). Federico Fellini: His Life and Work. New York: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-21168-5- Miller, D. A. (2008). 8½. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Further reading

General

- Angelucci, Gianfranco (2014). Giulietta Masina, attrice e sposa di Federico Fellini (Ill., 200 pp.). Roma: Edizioni Sabinae - Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia.

- Arpa, Angelo (2010). La dolce vita di Federico Fellini. Roma: Edizioni Sabinae.

- Ashough, Jamshid (2016). L'Enigma di un Genio, capire il linguaggio di Federico Fellini (Ill., 464 pp.). Pescara: Edizioni Ass. Cult. Zona Franca

- Bertozzi, Marco, Giuseppe Ricci, and Simone Casavecchia (eds.)(2002–2004). BiblioFellini. 3 vols. Rimini: Fondazione Federico Fellini.

- Betti, Liliana (1979). Fellini: An Intimate Portrait. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

- Bondanella, Peter (ed.)(1978). Federico Fellini: Essays in Criticism. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cianfarani, Carmine (ed.) (1985). Federico Fellini: Leone d'Oro, Venezia 1985. Rome: Anica.

- Fellini, Federico (2008). The Book of Dreams. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 0847831353.

- Merlino, Benito (2007). Fellini. Paris: Gallimard.ISBN 9782070335084.

- Minuz, Andrea (2015, translation by Marcus Perryman). Political Fellini: Journey to the End of Italy . Berghahn Books.

- Panicelli, Ida, and Antonella Soldaini (ed.)(1995). Fellini: Costumes and Fashion. Milan: Edizioni Charta. ISBN 88-86158-82-3.

- Perugini, Simone (2009). Nino Rota e le musiche per il Casanova di Federico Fellini. Roma: Edizioni Sabinae.

- Rohdie, Sam (2002). Fellini Lexicon. London: BFI Publishing.

- Scolari, Giovanni (2009). L'Italia di Fellini. Roma: Edizioni Sabinae.

- Tornabuoni, Lietta (1995). Federico Fellini. Preface Martin Scorsese. New York: Rizzoli.

- Walter, Eugene (2002). Milking the Moon: A Southerner's Story of Life on This Planet. Ed. Katherine Clark. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-609-80965-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Federico Fellini. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Federico Fellini |

Fellini Official site (in English)

Fellini Foundation Official Rimini web site (in Italian)

Fondation Fellini pour le cinéma Swiss web site (in French)

Federico Fellini on IMDb

Federico Fellini at the TCM Movie Database

Works by or about Federico Fellini in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

Federico Fellini biography on Lambiek Comiclopedia

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP