Carlos Menem

| Carlos Menem | |

|---|---|

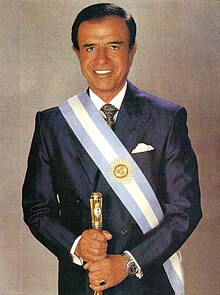

Official presidential portrait of Menem | |

| President of Argentina | |

In office 8 July 1989 – 10 December 1999 | |

| Vice President | Eduardo Duhalde (1989–1991) None (1991–1995) Carlos Ruckauf (1995–1999) |

| Preceded by | Raúl Alfonsín |

| Succeeded by | Fernando de la Rúa |

| National Senator of Argentina | |

Incumbent | |

Assumed office 10 December 2005 | |

| Constituency | La Rioja |

| Governor of La Rioja | |

In office 10 December 10 – 8 July 1989 | |

| Vice Governor | Bernabé Arnaudo |

| Preceded by | Guillermo Jorge Piastrellini (de facto) |

| Succeeded by | Bernabé Arnaudo |

In office 25 May 1973 – 24 March 1976 | |

| Preceded by | Julio Raúl Luchesi (de facto) |

| Succeeded by | Osvaldo Héctor Pérez Battaglia (de facto) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Carlos Saúl Menem (1930-07-02) 2 July 1930 Anillaco, La Rioja, Argentina |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Political party | Justicialist |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Relations | Saúl Menem Mohibe Akil |

| Children | 4, including Zulema María Eva Menem |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature |  |

Carlos Saúl Menem Akil (born 2 July 1930) is an Argentine politician who was President of Argentina from July 8, 1989 to December 10, 1999. He has been a Senator for La Rioja Province since December 10, 2005.

Born in Anillaco, Menem became a Peronist during a visit to Buenos Aires. He led the party in his home province of La Rioja, and was elected governor in 1973. He was deposed and detained during the 1976 Argentine coup d'état, and was elected governor again in 1983. He defeated the Buenos Aires governor Antonio Cafiero in the primary elections for the 1989 presidential elections, which he won. Hyperinflation forced outgoing president Raúl Alfonsín to resign early, shortening the presidential transition.

Menem supported the Washington Consensus, and tackled inflation with the Convertibility plan in 1991. The plan was complemented by a series of privatizations, and was a success. Argentina re-established diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom, suspended since the 1982 Falklands War, and developed special relations with the United States. The country suffered two terrorist attacks. The Peronist victory in the 1993 midterm elections allowed him to force Alfonsín to sign the Pact of Olivos for the 1994 amendment of the Argentine Constitution. This amendment allowed Menem to run for re-election in 1995, which he won. A new economic crisis began, and the opposing parties formed a political coalition that won the 1997 midterm elections and the 1999 presidential election.

Menem ran for the presidency again in 2003, but faced with a likely defeat in a ballotage against Néstor Kirchner, he chose to pull out of the ballotage, effectively handing the presidency to Kirchner. He was elected senator for La Rioja in 2005. At 88, he is currently the oldest living former Argentine president.

Contents

1 Early life and education

2 Governor of la Rioja

2.1 1st term (1973–1976) and detainment

2.2 2nd and 3rd terms (1983–1989)

3 Presidential elections

4 Presidency

4.1 Economic policy

4.2 Domestic policy

4.3 Armed forces

4.4 Terrorist attacks

4.5 Foreign policy

5 Post-presidency

5.1 Corruption charges

6 Public image

7 Honour

7.1 Foreign honour

8 References

9 Bibliography

10 External links

Early life and education

Carlos Saúl Menem was born in 1930 in Anillaco, a small town in the mountainous north of La Rioja Province, Argentina. His parents, Saúl Menem and Mohibe Akil, were Syrian nationals from Yabroud who had emigrated to Argentina. He attended elementary and high school in La Rioja, and joined a basketball team during his university studies. He visited Buenos Aires in 1951 with the team, and met the president Juan Perón and his wife Eva Perón. This influenced Menem to become a Peronist. He studied law at the National University of Córdoba, graduating in 1955.[2]

After President Juan Peron's overthrow in 1955, Menem was briefly incarcerated. He later joined the successor to the Peronist Party, the Justicialist Party (Partido Justicialista) (PJ). He was elected president of its La Rioja Province chapter in 1973. In that capacity, he was included in the flight to Spain that brought Perón back to Argentina after his long exile.[3] According to the Peronist politician Juan Manuel Abal Medina, Menem played no special part in the event.[4]

Governor of la Rioja

1st term (1973–1976) and detainment

Menem was elected governor in 1973, when the proscription over Peronism was lifted. He was deposed during the 1976 Argentine coup d'état that deposed the president Isabel Martínez de Perón. He was accused of corruption, and having links with the guerrillas of the Dirty War. He was detained on March 25, kept for a week at a local regiment, and then moved to a temporary prison at the ship "33 Orientales" in Buenos Aires. He was detained alongside former ministers Antonio Cafiero, Jorge Taiana, Miguel Unamuno, José Deheza, and Pedro Arrighi, the unionists Jorge Triaca, Diego Ibáñez, and Lorenzo Miguel, the diplomat Jorge Vázquez, the journalist Osvaldo Papaleo, and the former president Raúl Lastiri. He shared a cell with Pedro Eladio Vázquez, Juan Perón's personal physician. During this time he helped the chaplain Lorenzo Lavalle, despite being a Muslim.[5] In July he was sent to Magdalena, to a permanent prison. His wife Zulema visited him every week, but rejected his conversion to Christianity. His mother died during the time he was a prisoner, and dictator Jorge Rafael Videla denied his request to attend her funeral. He was released on July 29, 1978, on the condition that he live in a city outside his home province without leaving it. He settled in Mar del Plata.[5]

Menem met Admiral Eduardo Massera, who intended to run for president, and had public meetings with personalities such as Carlos Monzón, Susana Giménez, and Alberto Olmedo. As a result, he was forced to reside in another city, Tandil. He had to report daily to Chief of Police Hugo Zamora. This forced residence was lifted in February 1980. He returned to Buenos Aires, and then to La Rioja. He resumed his political activities, despite the prohibition, and was detained again. His new forced residence was in Las Lomitas, in Formosa Province. He was one of the last politicians to be released from prison by the National Reorganization Process.[5]

2nd and 3rd terms (1983–1989)

Military rule ended in 1983, and the radical Raúl Alfonsín was elected president. Menem ran for governor again, and was elected by a clear margin. The province benefited from tax regulations established by the military, which allowed increased industrial growth. His party got control of the provincial legislature, and he was re-elected in 1987 with 63% of the vote. The PJ was divided in two factions, the conservatives that still supported the political doctrines of Juan and Isabel Perón, and those who proposed a renovation of the party. The internal disputes ceased in 1987. Menem, with his prominent victory in his district, was one of the leading figures of the party, and disputed its leadership.[2]

Presidential elections

Carlos Menem and outgoing president Raúl Alfonsín, during the presidential transition.

Antonio Cafiero, who had been elected governor of Buenos Aires Province, led the renewal of the PJ, and was considered their most likely candidate for the presidency. Menem, on the other hand, was seen as a populist leader. Using a big tent approach, he got support from several unrelated political figures. As a result, he defeated Cafiero in the primary elections. He sought alliances with Bunge and Born, union leaders, former members of Montoneros, and the AAA, people from the church, "Carapintadas", etc. He promised a "revolution of production" and huge wage increases; but it was not clear exactly which policies he was proposing. The rival candidate, Eduardo Angeloz, tried to point out the mistakes made by Menem and Alfonsín.[6]Jacques de Mahieu, a French ideologue of the Peronist movement (and former Vichy collaborator), was photographed campaigning for Menem.[7] His campaign slogans were Siganme! (Follow me!) and No los voy a defraudar! (I won't let you down!)

The elections were held on May 14, 1989. Menem won by a wide margin, and became the new president. He was scheduled to take office on December 10, but inflation levels took a turn for the worse, growing into hyperinflation, causing public riots.[8] The outgoing president Alfonsín resigned and transferred power to Menem five months early, on July 8. Menem's accession marked the first time since Hipólito Yrigoyen took office in 1916 that an incumbent president peacefully transferred power to an elected successor from the opposition.[1]

Presidency

Economic policy

Play media

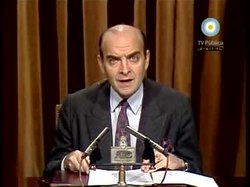

Play mediaDomingo Cavallo introduces the Convertibility Plan in 1991.

When Menem began his presidency, there was massive hyperinflation and a recession. Most economists of the time thought that the ideal solution was the Washington Consensus: reduce expenditures below the amount of money earned by the state, and open international commerce to free trade. Alfonsín had proposed similar plans in the past, alongside some privatization; but those projects were resisted by the PJ. The plan was resisted by factions benefiting from the protectionist policies, but the magnitude of the crisis convinced most politicians to change their minds. Menem, fearing that the crisis might force him to resign as well, embraced the Washington Consensus and rejected the traditional policies of Peronism. He invited the conservative politicians Álvaro Alsogaray and María Julia Alsogaray into his cabinet, as well as businessmen from Bunge and Born.[9]

Congress sanctioned the economic emergency law and the state reform law. The first allowed the president to reduce or remove subsidies, and the latter to privatize state enterprises – the first being telephones and airlines. These privatizations were beneficial to foreign creditors, who replaced their bonds with company shares.[10] Despite increased tax revenue, and the money from privatizations, the economy was still unstable. The Bunge and Born businessmen left the government in late 1989, amid a second round of hyperinflation. The first measure of the new minister of economy, Érman González, was a mandatory conversion of time deposits into government bonds: the Bonex plan. It generated more recession, but hyperinflation was reduced.[11][12] He also reduces social spending, including those for people with disabilities.[13]

His fourth minister of economy, Domingo Cavallo, was appointed in 1991. He deepened the neoliberal reforms. The Convertibility plan was sanctioned by the Congress, setting a one-to-one fixed exchange rate between the United States dollar and the new Argentine peso, which replaced the Austral. The law also limited public expenditures, but this was frequently ignored.[14] There was increased free trade to reduce inflation, and high taxes on sales and earnings to reduce the deficit caused by it.[10] Initially, the plan was a success: the capital flights ended, interest and inflation rates were lowered, and economic activity increased. The money from privatizations allowed Argentina to repurchase many of the Brady Bonds issued during the crisis.[15] The privatizations of electricity, water, and gas were more successful than previous ones. YPF, the national oil refinery, was privatized as well, but the state kept a good portion of the shares. The project to privatize the pension funds was resisted in Congress, and was approved as a mixed system that allowed both public and private options for workers. The national state also signed a fiscal pact with the provinces, so that they reduced their local deficits as well. Buenos Aires Province was helped with a fund that gave the governor a million pesos daily.[16]

Car and related exports (1983–2003) in millions of USD. During the 1990s, Argentina experienced growth on vehicles exports revenue.[17]

Although the Convertibility plan had positive consequences in the short term, it caused problems that surfaced later. Large numbers of employees of privatized state enterprises were fired, and unemployment grew to over 10%. Big compensation payments prevented an immediate public reaction. The free trade, and the expensive costs in dollars, forced private companies to reduce the number of workers as well, or risk bankruptcy. Unions were unable to resist the changes. People with low incomes, such as retirees and state workers, suffered under tax increases while their wages remained frozen. The provinces of Santiago del Estero, Jujuy and San Juan had their first violent riots. To compensate for these problems, the government started a number of social welfare programs, and restored protectionist policies over some sectors of the economy. It was difficult for Argentine companies to export, and easy imports damaged most national producers. The national budget soon slid into deficit.[18]

Cavallo Saralelo began a second wave of privatizations with the Correo Argentino and the nuclear power plants. He also limited the amount of money released to the provinces. He still had the full support of Menem, despite growing opposition within the PJ. The Mexican Tequila Crisis impacted the national economy, causing a deficit, recession, and a growth in unemployment. The government further reduced public expenditures, the wages of state workers, and raised taxes. The deficit and recession were reduced, but unemployment stayed high.[19] External debt increased. The crisis also proved that the economic system was vulnerable to capital flight.[20] The growing discontent over unemployment and the scandals caused by the privatization of the Correo led to Cavallo's removal as minister, and his replacement by Roque Fernández.[21] Fernández maintained Cavallo's fiscal austerity. He increased the price of fuels, sold the state shares of YPF to Repsol, fired state employees, and increased the value-added tax to 21%. He also undertook more privatization. A new labor law was met with resistance, both by Peronists, opposition parties, and unions, and could not be approved by Congress. The 1997 Asian financial crisis and the 1998 Russian financial crisis also affected the country with consequences that lasted longer than the Tequilla Crisis and started a depression.[21]

Domestic policy

Play media

Play mediaPresident Menem in a 1992 address outlining his plans for the reform of the nation's educational system, as well as for the privatization of the YPF oil concern, and of the pension system.

Menem began his presidency assuming a non-confrontational approach, and appointing people from the conservative opposition, and business people to his cabinet.[11] To prevent successful legal cases against the projected privatizations, the Supreme Court's numbers were increased from five to nine judges; the new judges ruled in support of Menem and usually had the majority.[10] Other institutions that restrained or limited executive power were controlled as well. When Congress resisted some of his proposals, he used the Necessity and Urgency Decree as an alternative to send bills to it. He even considered it feasible to dissolve Congress and rule by decree, but this step was never implemented.[22] In addition, he developed a bon vivant lifestyle, taking advantage of his authority. For instance, he made a journey from Buenos Aires to Pinamar driving a Ferrari Testarossa in less than two hours, violating speed limits. He divorced his wife Zulema Yoma and expanded the Quinta de Olivos presidential residence with a golf course, a small zoo, servants, barber, and even a buffoon.[23]

The swiftgate scandal broke out in 1990, as American investors were damaged by a case of corruption, and asked for assistance from the United States' Ambassador Terence Todman. Most of the ministers resigned as a result of it.[12] Cavallo was reassigned as minister of economy, and his successful economic plan turned him into a prominent figure in Menem's cabinet. Cavallo brought a number of independent economists to the cabinet, and Menem supported him by replacing Peronist politicians.[24] Both teams complemented each other. Both Menem and Cavallo tried to be recognized as the designer of the convertibility plan.[25]

Antonio Cafiero, a rival of Menem in the PJ, was unable to amend the constitution of the Buenos Aires province to run for a re-election. Duhalde stepped down from the vice presidency and became the new governor in the 1991 elections, turning the province into a powerful bastion. Menem also selected famous people with no political background to run for office in those elections including the singer Palito Ortega and racing driver Carlos Reutemann. The elections were a big success for the PJ.[26] After these elections, all of the PJ was aligned with Menem's leadership, with the exception of a small number of legislators known as the "Group of Eight". The opposition from the UCR was minimal, as the party was still discredited by the 1989 crisis. With such political influence, Menem began his proposal to amend the constitution to allow a re-election.[27] The party did not have the required super majority in the Congress to call for it. The PJ was divided, as other politicians intended to replace Menem in 1995, or negotiate their support. The UCR was divided as well, as Alfonsín opposed the proposal, but governors Angeloz and Massaccesi were open for negotiations. The victory in the 1993 elections strengthened his proposal, which was approved by the Senate. Menem called for a non-binding referendum on the proposal, to increase pressure on the radical deputies. He also sent a bill to the Congress to modify the majority requirements. Alfonsín met with Menem and agreed to support the proposal in exchange for amendments that would place limits on presidential power. This negotiation is known as the Pact of Olivos. The capital city of Buenos Aires would be allowed to elect its own chief of government. Presidential elections would use a system of ballotage, and the president could only be re-elected once. The electoral college was abolished, replaced by direct elections. The provinces would be allowed to elect a third senator; two for the majority party and one for the first minority. The Council of Magistrates of the Nation would have the power to propose new judges, and the Necessity and Urgency Decrees would have a reduced scope.[28]

Despite of the internal opposition of Fernando de la Rúa, Alfonsín got his party to approve the pact. He reasoned that Menem would be supported by the eventual referendum, that many legislators would turn to his side, and he would eventually be able to amend the constitution reinforcing presidential power rather than limiting it. Still, as both sides feared a betrayal, all the contents of the pact were included as a single proposal, not allowing the Constituent Assembly to discuss each one separately. The Broad Front, a new political party composed of former Peronists, led by Carlos Álvarez, grew in the elections for the Constituent Assembly.[29] Both the PJ and the UCR respected the pact, which was completely approved. Duhalde made a similar amendment to the constitution of the Buenos Aires province, in order to be re-elected in 1995. Menem won the elections with more than 50% of the vote, followed by José Octavio Bordón, and Carlos Álvarez. The UCR finished third in the elections for the first time.[30]

Growing unemployment increased popular resistance against Menem after his re-election. There were several riots and demonstrations in the provinces, unions opposed the economic policies, and the opposing parties organized the first cacerolazos. Estanislao Esteban Karlic replaced Antonio Quarracino as the head of the Argentine Episcopal Conference, which led to a growing opposition to Menem from the Church. The teachers' unions established a "white tent" at the Congressional plaza as a form of protest. The first piqueteros operated in Cutral Có, and this protest method was soon imitated in the rest of the country. His authority in the PJ was also held in doubt, as he was unable to run for another re-election and the party sought a candidate for the 1999 elections. This led to a fierce rivalry with Duhalde, the most likely candidate. Menem attempted to undermine his chances, and proposed a new amendment to the constitution allowing him to run for an unlimited number of re-elections. He also started a judicial case, claiming that his inability to run for a third term was a proscription. Several scandals erupted, such as the scandal over Argentine arms sales to Ecuador and Croatia, the Río Tercero explosion that may have destroyed evidence, the murder of the journalist José Luis Cabezas, and the suicide of Alfredo Yabrán, who may have ordered it. The PJ lost the 1997 midterm elections against the UCR and the FREPASO united in a political coalition, the Alliance for Work, Justice and Education (Alianza). The Supreme Court confirmed that Menem was unable to run for a third re-election. Duhalde became the candidate for the presidential elections, and lost to the candidate for the Alianza ticket, Fernando de la Rúa.[31]

Armed forces

Argentina was still divided by the aftermath of the Dirty War. Menem proposed an agenda of national reconciliation. First, he arranged the repatriation of the body of Juan Manuel de Rosas, a controversial 19th century governor, and proposed to reconcile his legacy with those of Bartolomé Mitre and Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, who also fought in the Argentine Civil Wars. Menem intended to use the reconciliation of these historical Argentine figures as a metaphor for the reconciliation of the Dirty War. However, although the repatriation and acceptance of Rosas was a success, the acceptance of the military regime was not.[32]

The military leaders of the National Reorganization Process, convicted in the 1985 Trial of the Juntas, received presidential pardons, despite popular opposition to them. This was an old request of the Carapintadas in previous years. However, Menem did not apply their proposed changes to the military. The colonel, Mohamed Alí Seineldín, who was also pardoned, started a new mutiny, killing two military men. Unlike the mutinies that took place during the presidency of Alfonsín, the military fully obeyed Menem's orders for a forceful repression. Seineldín was utterly defeated, and sentenced to life imprisonment. This was the last military mutiny in Argentina.[33]

The president effected drastic cuts to the military budget, and privatized military factories. Menem appointed Lt. Gen. Martín Balza, who had performed well during the repression of Seineldín's mutiny, as the Army's General Chief of Staff (head of the military hierarchy). The death of a conscript soldier in 1994, victim of abuses by his superiors, led to the abolition of conscription in the country. The following year, Balza voiced the first institutional self-criticism of the armed forces during the Dirty War, saying that obedience did not justify the actions committed in those years.[34]

Terrorist attacks

Demonstration during an anniversary of the AMIA bombing.

The Israeli embassy suffered a terrorist attack on March 17, 1992. It was perceived as a consequence of Argentina's involvement in the Gulf War. Although Hezbollah claimed responsibility for it, the Supreme Court investigated several other hypotheses. The Court wrote a report in 1996 suggesting that it could have been the explosion of an arms cache stored in the basement. Another hypothesis was that the attack could have been performed by Jewish extremists, in order to cast blame on Muslims and thwart the peace negotiations. The Court finally held Hezbollah responsible for the attack in May 1999.[35]

The Argentine Israelite Mutual Association suffered a terrorist attack with a car bomb on July 18, 1994, which killed eighty-five people. It was the most destructive terrorist attack in the history of Latin America. The attack was universally condemned and 155,000 people manifested their concern in a demonstration at the Congressional plaza; but Menem did not attend.[36] The legal case stayed unresolved during the remainder of Menem's presidency.[37] Menem had suggested, in the first press conference, that former Carapintada leaders may be responsible of the attack, but this idea was rejected by the minister of defense several hours later.[38] The CIA office in Buenos Aires initially considered it a joint Iranian-Syrian attack, but some days later considered it just an Iranian attack. Menem and Mossad also preferred this line of investigation.[39] As a result of the attack, the Jewish community in Argentina had increased influence over Argentine politics.[36] Years later, the prosecutor Alberto Nisman charged Menem with covering up a local connection to the attack, as the local terrorists may have been distant Syrian relatives of the Menem family. However, Menem was never tried for this suspected cover up,[40] and on 18 January 2015, Nisman was found dead of a gunshot to his head at his home in Buenos Aires.[41][42]

Foreign policy

Menem and Chilean president Patricio Aylwin, in 1993.

During his presidency, Argentina aligned with the United States, and had special relations with the country.[43] Menem had a positive relation with US president George H. W. Bush, and maintained it with his successor Bill Clinton. The country left the Non-Aligned Movement, and the Cóndor missile program was discontinued. Argentina supported all the international positions of the US, and sent forces to the Gulf War, and the peace keeping efforts after the Kosovo War.[44] The country was accepted as a Major non-NATO ally, but not as a full member.[45]

Menem's government re-established relations with the United Kingdom, suspended since the Falklands War, after Margaret Thatcher left office in 1990. The discussions on the Falkland Islands sovereignty dispute were temporarily given a lower priority, and the focus shifted to discussions of fishing rights.[44] He also settled all remaining border issues with Chile. The Lago del Desierto dispute had an international arbitration, favourable to Argentina. The only exception was the dispute over the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, which is still open.[44]

In 1991 Menem became the first head of state of Argentina to make a diplomatic visit to Israel. He proposed to mediate between Israel and Syria in their negotiations over the Golan Heights. The diplomatic relations were damaged by the lack of results in the investigations over the two terrorist attacks.[46]

Post-presidency

Menem ran in 2003 and won the greatest number of votes, 24%, in the first round of the April 27, 2003 presidential election; but votes were split among numerous parties. Under the 1994 amendment, a presidential candidate can win outright by winning 45% of the vote, or 40% if the margin of victory is 10 or more percentage points. This set the stage for Argentina's first-ever ballotage between Menem and second-place finisher, and fellow Peronist, Néstor Kirchner, who had received 22%, was scheduled for May 18. However, by that time, Menem had become very unpopular. Polls predicted that he faced almost certain defeat by Kirchner in the runoff. Most polls showed Kirchner taking at least 60 percent of the vote, and at least one poll showed Menem losing by as many as 50 points.[47][48] To avoid a humiliating defeat, Menem withdrew his candidacy on May 14, effectively handing the presidency to Kirchner.[49]

Ángel Maza, the elected governor of La Rioja, was allied with Menem, and had campaigned for him. However, weak provincial finances forced Maza to switch his support to Kirchner, which weakened Menem's influence even further.[50] In June 2004 Menem announced that he had founded a new faction within the PJ, called "People's Peronism". He announced his intention to run in the 2007 election. In 2005, the press reported that he was trying to form an alliance with his former minister of economy Cavallo to fight in the parliamentary elections. Menem said that there had been only preliminary conversations and an alliance did not result. In the October 23, 2005 elections, Menem won the minority seat in the Senate representing his province of birth. The two seats allocated to the majority were won by President Kirchner's faction, locally led by Ángel Maza.[51]

Menem ran for Governor of La Rioja in August 2007, but was defeated. He finished in third place with about 22% of the vote.[52] This was viewed as a catastrophic defeat, signaling the end of his political dominance in La Rioja. It was the first time in 30 years that Menem had lost an election. Following this defeat in his home province, he withdrew his candidacy for president. At the end of 2009 he announced that he intended to run for the presidency again in the 2011 elections.[53] but ran for a new term as senator instead.[54]

Corruption charges

On June 7, 2001, Menem was arrested over a weapons export scandal. The scheme was based on exports to Ecuador and Croatia in 1991 and 1996. He was held under house arrest until November. He appeared before a judge in late August 2002 and denied all charges. Menem and his Chilean second wife Cecilia Bolocco, who had had a child since their marriage in 2001, fled to Chile. Argentine judicial authorities repeatedly requested Menem's extradition to face embezzlement charges. This request was rejected by the Chilean Supreme Court as under Chilean law, people cannot be extradited for questioning. On December 22, 2004, after the arrest warrants were cancelled, Menem returned with his family to Argentina. He still faced charges of embezzlement and failing to declare illegal funds in a Swiss bank.[55] He was declared innocent of those charges in 2013.[56]

In August 2008, the BBC reported that Menem was under investigation for his role in the 1995 Río Tercero explosion, which is alleged to have been part of the weapons scandal involving Croatia and Ecuador.[57] Following an Appeals Court ruling that found Menem guilty of aggravated smuggling, he was sentenced to seven years in prison on June 13, 2013, for his role in illegally smuggling weapons to Ecuador and Croatia; his position as senator earned him immunity from incarceration, and his advanced age (82) afforded him the possibility of house arrest. His minister of defense during the weapons sales, Oscar Camilión, was concurrently sentenced to five and a half years.[58]

In December 2008, the German multinational Siemens agreed to pay an $800 million fine to the United States government, and approximately €700 million to the German government, to settle allegations of bribery.[59] The settlement revealed that Menem had received about US$2 million in bribes from Siemens in exchange for awarding the national ID card and passport production contract to Siemens; Menem denied the charges but nonetheless agreed to pay the fine.[60]

On December 1, 2015, Menem was also found guilty of embezzlement, and sentenced four and half years to prison. Domingo Cavallo, his economy minister, and Raúl Granillo Ocampo, Menem's former minister of justice, also received prison sentences of more than three years for participating in the scheme, and were ordered to repay hundreds of thousands of pesos’ worth of illegal bonuses.[61]

Public image

In the early days, Menem sported an image similar to the old caudillos, such as Facundo Quiroga and Chacho Peñaloza. He groomed his sideburns in a similar style. His presidential inauguration was attended by several gauchos.[62] Contrary to Peronist tradition, Menem did not prepare huge rallies in the Plaza de Mayo to address the people from the balcony of the Casa Rosada. Instead, he took full advantage of mass media, such as television.[63]

Honour

Foreign honour

Malaysia : Honorary Recipient of the Order of the Crown of the Realm (1991)[64]

Malaysia : Honorary Recipient of the Order of the Crown of the Realm (1991)[64]

References

^ ab Edwards, p. 162

^ ab Roberto Ortiz de Zárate (March 9, 2015). "Carlos Menem" (in Spanish). Barcelona Centre for International Affairs. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

^ "El chárter histórico" [The historical charter] (in Spanish). Clarín. October 12, 1997. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

^ Miguel Bonasso (November 16, 2003). "La historia secreta del regreso" [The secret history of the return] (in Spanish). Página 12. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

^ abc "Menem 1976–1981: El mismo preso, otra historia" [Menem 1976–1981: the same prisoner, another story] (in Spanish). Clarín. June 8, 2001. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

^ Romero, p. 283

^ "La Odessa que creó Perón", Pagina/12, December 15, 2002 (interview with Uki Goni) (in Spanish)

^ Romero, pp. 284–285

^ Romero, pp. 287–288

^ abc Romero, p. 289

^ ab Edwards, p. 103

^ ab Romero, p. 290

^ https://www.pagina12.com.ar/43813-el-ajuste-donde-mas-duele

^ Edwards, pp. 104–105

^ Romero, p. 291

^ Romero, pp. 292–293

^ "Argentina exports stacked". The Observatory of Economic Complexity.

^ Romero, pp. 293–294

^ Romero, p. 306

^ McGuire, p. 222

^ ab Romero, pp. 308–309

^ Romero, p. 295

^ Romero, p. 296

^ Romero, p. 292

^ Romero, pp. 297–298

^ Romero, p. 300

^ Romero, p. 301

^ Romero, p. 304

^ Romero, p. 305

^ Romero, pp. 306–307

^ Romero, pp. 310–315

^ Johnson, p. 107

^ Romero, pp. 301–302

^ Romero, p. 302

^ Ruggiero, pp. 87–88

^ ab Ruggiero, p. 90

^ Levine, pp. 1–3

^ Ruggiero, p. 89

^ Ruggiero, p. 88

^ Fernholz, Tim (February 5, 2015). "The US had ties to an Argentine terror investigation that ended with a prosecutor's mysterious death". Quartz. Atlantic Media. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

^ "Muerte de Nisman: la media hora que es un agujero negro en la causa" [Nisman's death: the half-hour which is a black hole in the case]. Infojus Noticias (in Spanish). Ifnojus Noticias. 11 February 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.El médico de Swiss Medical ... no tenía dudas de que se trataba de una muerte violenta...

^ "Los enigmas del caso Nisman" [The mysteries of the Nisman case]. La Nacion (in Spanish). La Nacion. 9 March 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.23 hs - Llega la ambulancia de Swiss Medical y constantan la muerte.

^ Francisco Corigliano. "La dimensión bilateral de las relaciones entre Argentina y Estados Unidos durante la década de 1990: El ingreso al paradigma de "Relaciones especiales"" [The bilateral plane of the relations between Argentina and the United States during the 1990s: the entry to the paradigm of the "special relations"] (in Spanish). CARI. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

^ abc Romero, p. 303

^ Carlos Escudé and Andrés Cisneros. "Las medidas adoptadas por el gobierno norteamericano en el apartado estratégico de la agenda bilateral" [The measures taken by the American government in the strategic aspect of the billateral agenda] (in Spanish). CARI. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

^ Reich, p. 52

^ Uki Goñi (May 15, 2003). "Menem bows out of race for top job". The Guardian. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

^ "Menem pierde el invicto y la fama". Página/12.

^ "Don't cry for Menem". The Economist. March 15, 2003. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

^ Giraudy, p. 107

^ "Menem sufrió una dura derrota en La Rioja" [Menem suffered a hard setback in La Rioja] (in Spanish). La Gaceta. October 25, 2005. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

^ "Former Argentine President Menem loses gubernatorial race", Associated Press (International Herald Tribune), 20 August 2007

^ "Menem se anota en la pelea presidencial" [Menem signs for the presidential fight] (in Spanish). La Nación. December 27, 2009. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

^ "Cristina ganó en La Rioja de la mano de Menem" [Cristina won in La Rioja alongside Menem] (in Spanish). Perfil. October 24, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

^ "Menem arrives on Argentine soil". BBC. December 23, 2004. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

^ Hernán Capiello (September 21, 2013). "Menem, absuelto en el juicio por su cuenta en Suiza" [Menem, absolved in the case over his account in Switzerland] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

^ "Americas | Menem probed over 1995 explosion". BBC News. 2008-08-16. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

^ "Argentina: Ex-president gets 7 years in prison for arms smuggling". CNN. June 13, 2013.

^ Crawford, David (2008-12-16). "''Wall Street Journal''". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

^ (AFP) – Dec 17, 2008 (2008-12-17). "Google News". Google. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

^ Jonathan Gilbert (December 1, 2015). "Ex-President of Argentina Is Sentenced in Embezzlement Case". The New York Times. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

^ Johnson, p. 118

^ Romero, p. 298

^ "Senarai Penuh Penerima Darjah Kebesaran, Bintang dan Pingat Persekutuan Tahun 1991" (PDF).

Bibliography

Edwards, Todd (2008). Argentina: A global studies handbook. United States: ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1-85109-987-0. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

Giraudy, Agustina (2015). Democrats and Autocrats: Pathways of Subnational Undemocratic Regime continuity within democratic countries. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870686-1.

Johnson, Lyman (2004). Death, dismemberment, and memory: body politics in Latin America. United States: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-3200-5.

Levine, Anete (2015). Landscapes of Memory and Impunity: The Aftermath of the AMIA Bombing in Jewish Argentina. United States: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-29749-4.

McGuire, James (1997). Peronism without Perón. United States: Stanford University Press.

Reich, Bernard (2008). Historical Dictionary of Israel. United States: Scarecrow Press.

Romero, Luis Alberto (2013) [1994]. A History of Argentina in the Twentieth Century. United States: The Pennsylvania University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-06228-0.

Ruggiero, Kristin (2005). The Jewish Diaspora in Latin America and the Caribbean: Fragments of Memory. United Kingdom: Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-84519-414-7. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carlos Menem. |

- Launch of new faction (from the BBC)

- Chile declines extradition request (from the BBC)

- Menem arrives on Argentine soil (from the BBC)

Appearances on C-SPAN

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Julio Raúl Luchesi (de facto) | Governor of La Rioja 1973–1976 1983–1989 | Succeeded by Osvaldo Héctor Pérez Battaglia (de facto) |

| Preceded by Guillermo Jorge Piastrellini (de facto) | Succeeded by Bernarbé Arnaudo | |

| Preceded by Raúl Alfonsín | President of Argentina 1989–1999 | Succeeded by Fernando de la Rúa |

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP