East India Company

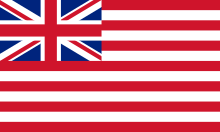

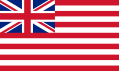

Company flag (1801) | |

Coat of arms (1698) | |

Former type | Public |

|---|---|

| Industry | International trade, Opium trafficking |

| Fate | Dissolved, after being mostly nationalised in 1858 |

| Founded | 31 December 1600 |

| Founders | John Watts, George White |

| Defunct | 1 June 1874 (1874-06-01) |

| Headquarters | London, England (Great Britain) |

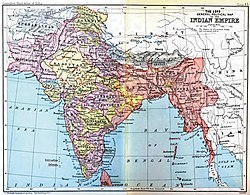

Imperial entities of India | |

| Dutch India | 1605–1825 |

|---|---|

| Danish India | 1620–1869 |

| French India | 1668–1954 |

Portuguese India (1505–1961) | |

| Casa da Índia | 1434–1833 |

| Portuguese East India Company | 1628–1633 |

British India (1612–1947) | |

| East India Company | 1612–1757 |

| Company rule in India | 1757–1858 |

| British Raj | 1858–1947 |

| British rule in Burma | 1824–1948 |

| Princely states | 1721–1949 |

| Partition of India | 1947 |

The East India Company (EIC), also known as the Honourable East India Company (HEIC) or the British East India Company and informally as John Company,[1] was an English and later British joint-stock company,[2] formed to trade with the East Indies (in present-day terms, Maritime Southeast Asia), but ended up trading mainly with Qing China and seizing control of large parts of the Indian subcontinent.

Originally chartered as the "Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies", the company rose to account for half of the world's trade[3][dubious ], particularly in basic commodities including cotton, silk, indigo dye, salt, spices, saltpetre, tea, and opium. The company also ruled the beginnings of the British Empire in India.[3]

The company received a Royal Charter from Queen Elizabeth I on 31 December 1600, coming relatively late to trade in the Indies. Before them the Portuguese Estado da Índia had traded there for much of the 16th century and the first of half a dozen Dutch Companies sailed to trade there from 1595, which amalgamated in March 1602 into the United East Indies Company (VOC), which introduced the first permanent joint stock from 1612 (meaning investment into shares did not need to be returned, but could be traded on a stock exchange). By contrast, wealthy merchants and aristocrats owned the EIC's shares.[4] Initially the government owned no shares and had only indirect control until 1657 when permanent joint stock was established.[5]

During its first century of operation, the focus of the company was trade, not the building of an empire in India. Company interests turned from trade to territory during the 18th century as the Mughal Empire declined in power and the East India Company struggled with its French counterpart, the French East India Company (Compagnie française des Indes orientales) during the Carnatic Wars of the 1740s and 1750s. The battles of Plassey and Buxar, in which the British defeated the Bengali powers, left the company in control of Bengal and a major military and political power in India. In the following decades it gradually increased the extent of the territories under its control, controlling the majority of the Indian subcontinent either directly or indirectly via local puppet rulers under the threat of force by its Presidency armies, much of which were composed of native Indian sepoys.

By 1803, at the height of its rule in India, the British East India company had a private army of about 260,000—twice the size of the British Army, with Indian revenues of £13,464,561, and expenses of £14,017,473.[6][7] The company eventually came to rule large areas of India with its private armies, exercising military power and assuming administrative functions.[8]Company rule in India effectively began in 1757 and lasted until 1858, when, following the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Government of India Act 1858 led to the British Crown's assuming direct control of the Indian subcontinent in the form of the new British Raj.

Despite frequent government intervention, the company had recurring problems with its finances. It was dissolved in 1874 as a result of the East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act passed one year earlier, as the Government of India Act had by then rendered it vestigial, powerless, and obsolete. The official government machinery of British India had assumed its governmental functions and absorbed its armies.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Origins

1.2 Formation

2 Early voyages to the East Indies

3 Foothold in India

4 Expansion

4.1 Japan

4.2 Mughal convoy piracy incident of 1695

5 Forming a complete monopoly

5.1 Trade monopoly

5.2 Saltpetre trade

6 Basis for the monopoly

6.1 Colonial monopoly

6.2 East India Company Army and Navy

6.2.1 Expansion and conquest

6.3 Opium trade

7 Regulation of the company's affairs

7.1 Writers

7.2 Financial troubles

7.3 Regulating Acts of Parliament

7.3.1 East India Company Act 1773

7.3.2 East India Company Act 1784 (Pitt's India Act)

7.3.3 Act of 1786

7.3.4 East India Company Act 1793 (Charter Act)

7.3.5 East India Company Act 1813 (Charter Act)

7.3.6 Government of India Act 1833

7.3.7 English Education Act 1835

7.3.8 Government of India Act 1853

8 Indian Rebellion and disestablishment

9 Establishments in Britain

10 Legacy and criticisms

11 Symbols

11.1 Flags

11.2 Coat of arms

11.3 Merchant mark

12 Ships

13 Records

14 See also

15 Notes and references

16 Further reading

16.1 Historiography

17 External links

History

Origins

James Lancaster commanded the first East India Company voyage in 1601

Soon after the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, the captured Spanish and Portuguese ships with their cargoes enabled English voyagers to potentially travel the globe in search of riches.[9] London merchants presented a petition to Queen Elizabeth I for permission to sail to the Indian Ocean.[10] The aim was to deliver a decisive blow to the Spanish and Portuguese monopoly of Far Eastern Trade.[11] Elizabeth granted her permission and on 10 April 1591 James Lancaster in the Edward Bonaventure with two other ships sailed from Torbay around the Cape of Good Hope to the Arabian Sea on one of the earliest English overseas Indian expeditions. Having sailed around Cape Comorin to the Malay Peninsula, they preyed on Spanish and Portuguese ships there before returning to England in 1594.[10]

The biggest capture that galvanised English trade was the seizing of the great Portuguese Carrack Madre de Deus by Sir Walter Raleigh and the Earl of Cumberland at the Battle of Flores (1592).[12] When she was brought in to Dartmouth she was the largest vessel that had been seen in England and her cargo consisted of chests filled with jewels, pearls, gold, silver coins, ambergris, cloth, tapestries, pepper, cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg, benjamin, red dye, cochineal and ebony.[13]:125–27 Equally valuable was the ship's rutter containing vital information on the China, India, and Japan trades. These riches aroused the English to engage in this opulent commerce.[12]

In 1596, three more English ships sailed east but were all lost at sea.[10] A year later however saw the arrival of Ralph Fitch, an adventurer merchant who, along with his companions, had made a remarkable fifteen-year overland journey to Mesopotamia, the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean, India and Southeast Asia.[14] Fitch was then consulted on the Indian affairs and gave even more valuable information to Lancaster.[15]

Formation

On 22 September 1599, a group of merchants met and stated their intention "to venture in the pretended voyage to the East Indies (the which it may please the Lord to prosper), and the sums that they will adventure", committing £30,133.[16][17] Two days later, "the Adventurers" reconvened and resolved to apply to the Queen for support of the project.[17] Although their first attempt had not been completely successful, they nonetheless sought the Queen's unofficial approval to continue. They bought ships for their venture and increased their capital to £68,373.

The Adventurers convened again a year later, on 31 December, and this time they succeeded; the Queen granted a Royal Charter to "George, Earl of Cumberland, and 215 Knights, Aldermen, and Burgesses" under the name, Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading with the East Indies.[10][18] For a period of fifteen years, the charter awarded the newly formed company a monopoly on English trade with all countries east of the Cape of Good Hope and west of the Straits of Magellan.[18] Any traders in breach of the charter without a licence from the company were liable to forfeiture of their ships and cargo (half of which went to the Crown and the other half to the company), as well as imprisonment at the "royal pleasure".[19]

The governance of the company was in the hands of one governor and 24 directors or "committees", who made up the Court of Directors. They, in turn, reported to the Court of Proprietors, which appointed them. Ten committees reported to the Court of Directors. According to tradition, business was initially transacted at the Nags Head Inn, opposite St Botolph's church in Bishopsgate, before moving to India House in Leadenhall Street.[20]

Early voyages to the East Indies

Sir James Lancaster commanded the first East India Company voyage in 1601 aboard the Red Dragon.[21] After capturing a rich 1,200 ton Portuguese Carrack in the Malacca Straits the trade from the booty enabled the voyagers to set up two "factories" – one at Bantam on Java and another in the Moluccas (Spice Islands) before leaving.[22] They returned to England in 1603 to learn of Elizabeth's death but Lancaster was Knighted by the new King James I.[23] By this time the war with Spain had ended but the Company had successfully and profitably breached the Spanish and Portuguese monopoly, with new horizons opened for the English.[11]

In March 1604 Sir Henry Middleton commanded the second voyage. General William Keeling, a captain during the second voyage, led the third voyage aboard the Red Dragon from 1607 to 1610 along with the Hector under Captain William Hawkins and the Consent under Captain David Middleton.[24]

Early in 1608 Alexander Sharpeigh was appointed captain of the company's Ascension, and general or commander of the fourth voyage. Thereafter two ships, Ascension and Union (captained by Richard Rowles) sailed from Woolwich on 14 March 1607–08.[24] This expedition would be lost.[25]

| Year | Vessels | Total Invested £ | Bullion sent £ | Goods sent £ | Ships & Provisions £ | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1603 | 3 | 60,450 | 11,160 | 1,142 | 48,140 | |

| 1606 | 3 | 58,500 | 17,600 | 7,280 | 28,620 | |

| 1607 | 2 | 38,000 | 15,000 | 3,400 | 14,600 | Vessels lost |

| 1608 | 1 | 13,700 | 6,000 | 1,700 | 6,000 | |

| 1609 | 3 | 82,000 | 28,500 | 21,300 | 32,000 | |

| 1610 | 4 | 71,581 | 19,200 | 10,081 | 42,500 | |

| 1611 | 4 | 76,355 | 17,675 | 10,000 | 48,700 | |

| 1612 | 1 | 7,200 | 1,250 | 650 | 5,300 | |

| 1613 | 8 | 272,544 | 18,810 | 12,446 | ||

| 1614 | 8 | 13,942 | 23,000 | |||

| 1615 | 6 | 26,660 | 26,065 | |||

| 1616 | 7 | 52,087 | 16,506 |

Initially, the company struggled in the spice trade because of the competition from the already well-established Dutch East India Company. The company opened a factory in Bantam on the first voyage, and imports of pepper from Java were an important part of the company's trade for twenty years. The factory in Bantam was closed in 1683. During this time ships belonging to the company arriving in India docked at Surat, which was established as a trade transit point in 1608.

In the next two years, the company established its first factory in south India in the town of Machilipatnam on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. The high profits reported by the company after landing in India initially prompted James I to grant subsidiary licences to other trading companies in England. But in 1609 he renewed the charter given to the company for an indefinite period, including a clause that specified that the charter would cease to be in force if the trade turned unprofitable for three consecutive years.

Foothold in India

Red Dragon fought the Portuguese at the Battle of Swally in 1612, and made several voyages to the East Indies.

Jahangir investing a courtier with a robe of honour, watched by Sir Thomas Roe, English ambassador to the court of Jahangir at Agra from 1615 to 1618, and others

English traders frequently engaged in hostilities with their Dutch and Portuguese counterparts in the Indian Ocean. The company achieved a major victory over the Portuguese in the Battle of Swally in 1612, at Suvali in Surat. The company decided to explore the feasibility of gaining a territorial foothold in mainland India, with official sanction from both Britain and the Mughal Empire, and requested that the Crown launch a diplomatic mission.[26]

In 1612, James I instructed Sir Thomas Roe to visit the Mughal Emperor Nur-ud-din Salim Jahangir (r. 1605–1627) to arrange for a commercial treaty that would give the company exclusive rights to reside and establish factories in Surat and other areas. In return, the company offered to provide the Emperor with goods and rarities from the European market. This mission was highly successful, and Jahangir sent a letter to James through Sir Thomas Roe:[26]

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

Upon which assurance of your royal love I have given my general command to all the kingdoms and ports of my dominions to receive all the merchants of the English nation as the subjects of my friend; that in what place soever they choose to live, they may have free liberty without any restraint; and at what port soever they shall arrive, that neither Portugal nor any other shall dare to molest their quiet; and in what city soever they shall have residence, I have commanded all my governors and captains to give them freedom answerable to their own desires; to sell, buy, and to transport into their country at their pleasure.

For confirmation of our love and friendship, I desire your Majesty to command your merchants to bring in their ships of all sorts of rarities and rich goods fit for my palace; and that you be pleased to send me your royal letters by every opportunity, that I may rejoice in your health and prosperous affairs; that our friendship may be interchanged and eternal.— Nuruddin Salim Jahangir, Letter to James I.

Expansion

The company, which benefited from the imperial patronage, soon expanded its commercial trading operations. It eclipsed the Portuguese Estado da Índia, which had established bases in Goa, Chittagong, and Bombay, which Portugal later ceded to England as part of the dowry of Catherine of Braganza on her marriage to King Charles II. The East India Company also launched a joint attack with the Dutch United East India Company (VOC) on Portuguese and Spanish ships off the coast of China, which helped secure EIC ports in China.[27] The company established trading posts in Surat (1619), Madras (1639), Bombay (1668), and Calcutta (1690). By 1647, the company had 23 factories, each under the command of a factor or master merchant and governor, and 90 employees[clarification needed] in India. The major factories became the walled forts of Fort William in Bengal, Fort St George in Madras, and Bombay Castle.

In 1634, the Mughal emperor extended his hospitality to the English traders to the region of Bengal, and in 1717 completely waived customs duties for their trade. The company's mainstay businesses were by then cotton, silk, indigo dye, saltpetre, and tea. The Dutch were aggressive competitors and had meanwhile expanded their monopoly of the spice trade in the Straits of Malacca by ousting the Portuguese in 1640–41. With reduced Portuguese and Spanish influence in the region, the EIC and VOC entered a period of intense competition, resulting in the Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Within the first two decades of the 17th century, the Dutch East India Company or Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, (VOC) was the wealthiest commercial operation in the world with 50,000 employees worldwide and a private fleet of 200 ships. It specialised in the spice trade and gave its shareholders 40% annual dividend.[28]

The British East India Company was fiercely competitive with the Dutch and French throughout the 17th and 18th centuries over spices from the Spice Islands. Spices, at the time, could only be found on these islands, such as pepper, ginger, nutmeg, cloves and cinnamon could bring profits as high as 400 percent from one voyage.[29]

The tension was so high between the Dutch and the British East Indies Trading Companies that it escalated into at least four Anglo-Dutch Wars between them:[29] 1652–1654, 1665–1667, 1672–1674 and 1780–1784.

The Dutch Company maintained that profit must support the cost of war which came from trade which produced profit.[30]

Competition arose in 1635 when Charles I granted a trading licence to Sir William Courteen, which permitted the rival Courteen association to trade with the east at any location in which the EIC had no presence.[31]

In an act aimed at strengthening the power of the EIC, King Charles II granted the EIC (in a series of five acts around 1670) the rights to autonomous territorial acquisitions, to mint money, to command fortresses and troops and form alliances, to make war and peace, and to exercise both civil and criminal jurisdiction over the acquired areas.[32]

In 1689 a Mughal fleet commanded by Sidi Yaqub attacked Bombay. After a year of resistance the EIC surrendered in 1690, and the company sent envoys to Aurangzeb's camp to plead for a pardon. The company's envoys had to prostrate themselves before the emperor, pay a large indemnity, and promise better behaviour in the future. The emperor withdrew his troops, and the company subsequently re-established itself in Bombay and set up a new base in Calcutta.[33]

| Years | EIC | VOC | France | EdI | Denmark | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bengal | Madras | Bombay | Surat | EIC (total) | VOC (total) | |||||

| 1665–69 | 7,041 | 37,078 | 95,558 | 139,677 | 126,572 | 266,249 | ||||

| 1670–74 | 46,510 | 169,052 | 294,959 | 510,521 | 257,918 | 768,439 | ||||

| 1675–79 | 66,764 | 193,303 | 309,480 | 569,547 | 127,459 | 697,006 | ||||

| 1680–84 | 107,669 | 408,032 | 452,083 | 967,784 | 283,456 | 1,251,240 | ||||

| 1685–89 | 169,595 | 244,065 | 200,766 | 614,426 | 316,167 | 930,593 | ||||

| 1690–94 | 59,390 | 23,011 | 89,486 | 171,887 | 156,891 | 328,778 | ||||

| 1695–99 | 130,910 | 107,909 | 148,704 | 387,523 | 364,613 | 752,136 | ||||

| 1700-04 | 197,012 | 104,939 | 296,027 | 597,978 | 310,611 | 908,589 | ||||

| 1705-09 | 70,594 | 99,038 | 34,382 | 204,014 | 294,886 | 498,900 | ||||

| 1710–14 | 260,318 | 150,042 | 164,742 | 575,102 | 372,601 | 947,703 | ||||

| 1715–19 | 251,585 | 20,049 | 582,108 | 534,188 | 435,923 | 970,111 | ||||

| 1720–24 | 341,925 | 269,653 | 184,715 | 796,293 | 475,752 | 1,272,045 | ||||

| 1725–29 | 558,850 | 142,500 | 119,962 | 821,312 | 399,477 | 1,220,789 | ||||

| 1730–34 | 583,707 | 86,606 | 57,503 | 727,816 | 241,070 | 968,886 | ||||

| 1735–39 | 580,458 | 137,233 | 66,981 | 784,672 | 315,543 | 1,100,215 | ||||

| 1740–44 | 619,309 | 98,252 | 295,139 | 812,700 | 288,050 | 1,100,750 | ||||

| 1745–49 | 479,593 | 144,553 | 60,042 | 684,188 | 262,261 | 946,449 | ||||

| 1750–54 | 406,706 | 169,892 | 55,576 | 632,174 | 532,865 | 1,165,039 | ||||

| 1755–59 | 307,776 | 106,646 | 55,770 | 470,192 | 321,251 | 791,443 | ||||

| 1760–70 | 0 | |||||||||

| 1771–74 | 652,158 | 182,588 | 93,683 | 928,429 | 928,429 | |||||

| 1775–79 | 584,889 | 197,306 | 48,412 | 830,607 | 830,607 | |||||

| 1780–84 | 435,340 | 79,999 | 40,488 | 555,827 | 555,827 | |||||

| 1785–89 | 697,483 | 67,181 | 38,800 | 803,464 | 803,464 | |||||

| 1790–92 | 727,717 | 170,442 | 38,707 | 936,866 | 936,866 | |||||

Eventually, the East India Company seized control of Bengal and slowly the whole Indian subcontinent with its private armies, composed primarily of Indian sepoys. As historian William Dalrymple observes,

We still talk about the British conquering India, but that phrase disguises a more sinister reality. It was not the British government that seized India at the end of the 18th century, but a dangerously unregulated private company headquartered in one small office, five windows wide, in London, and managed in India by an unstable sociopath – [Robert] Clive.[6]

Japan

Document with the original vermilion seal of Tokugawa Ieyasu, granting trade privileges in Japan to the East India Company in 1613

In 1613, during the rule of Tokugawa Hidetada of the Tokugawa shogunate, the British ship Clove, under the command of Captain John Saris, was the first British ship to call on Japan. Saris was the chief factor of the EIC's trading post in Java, and with the assistance of William Adams, a British sailor who had arrived in Japan in 1600, he was able to gain permission from the ruler to establish a commercial house in Hirado on the Japanese island of Kyushu:

We give free license to the subjects of the King of Great Britaine, Sir Thomas Smythe, Governor and Company of the East Indian Merchants and Adventurers forever safely come into any of our ports of our Empire of Japan with their shippes and merchandise, without any hindrance to them or their goods, and to abide, buy, sell and barter according to their own manner with all nations, to tarry here as long as they think good, and to depart at their pleasure.[35]

However, unable to obtain Japanese raw silk for import to China and with their trading area reduced to Hirado and Nagasaki from 1616 onwards, the company closed its factory in 1623.[36]

Mughal convoy piracy incident of 1695

In September 1695, Captain Henry Every, an English pirate on board the Fancy, reached the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb, where he teamed up with five other pirate captains to make an attack on the Indian fleet on return from the annual pilgrimage to Mecca. The Mughal convoy included the treasure-laden Ganj-i-Sawai, reported to be the greatest in the Mughal fleet and the largest ship operational in the Indian Ocean, and its escort, the Fateh Muhammed. They were spotted passing the straits en route to Surat. The pirates gave chase and caught up with Fateh Muhammed some days later, and meeting little resistance, took some £50,000 to £60,000 worth of treasure.[37]

English, Dutch and Danish factories at Mocha

Every continued in pursuit and managed to overhaul Ganj-i-Sawai, which resisted strongly before eventually striking. Ganj-i-Sawai carried enormous wealth and, according to contemporary East India Company sources, was carrying a relative of the Grand Mughal, though there is no evidence to suggest that it was his daughter and her retinue. The loot from the Ganj-i-Sawai had a total value between £325,000 and £600,000, including 500,000 gold and silver pieces, and has become known as the richest ship ever taken by pirates.

In a letter sent to the Privy Council by Sir John Gayer, then governor of Bombay and head of the East India Company, Gayer claims that "it is certain the Pirates ... did do very barbarously by the People of the Ganj-i-Sawai and Abdul Ghaffar's ship, to make them confess where their money was." The pirates set free the survivors who were left aboard their emptied ships, to continue their voyage back to India.

When the news arrived in England it caused an outcry. To appease Aurangzeb, the East India Company promised to pay all financial reparations, while Parliament declared the pirates hostis humani generis ("enemies of the human race"). In mid-1696 the government issued a £500 bounty on Every's head and offered a free pardon to any informer who disclosed his whereabouts. When the East India Company later doubled that reward, the first worldwide manhunt in recorded history was underway.[38]

The plunder of Aurangzeb's treasure ship had serious consequences for the English East India Company. The furious Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb ordered Sidi Yaqub and Nawab Daud Khan to attack and close four of the company's factories in India and imprison their officers, who were almost lynched by a mob of angry Mughals, blaming them for their countryman's depredations, and threatened to put an end to all English trading in India. To appease Emperor Aurangzeb and particularly his Grand Vizier Asad Khan, Parliament exempted Every from all of the Acts of Grace (pardons) and amnesties it would subsequently issue to other pirates.[39]

An 18th-century depiction of Henry Every, with the Fancy shown engaging its prey in the background

British pirates that fought during the Child's War engaging the Ganj-i-Sawai

Depiction of Captain Every's encounter with the Mughal Emperor's granddaughter after his September 1695 capture of the Mughal trader Ganj-i-Sawai

Forming a complete monopoly

Trade monopoly

Rear view of the East India Company's Factory at Cossimbazar

The prosperity that the officers of the company enjoyed allowed them to return to Britain and establish sprawling estates and businesses, and to obtain political power. The company developed a lobby in the English parliament. Under pressure from ambitious tradesmen and former associates of the company (pejoratively termed Interlopers by the company), who wanted to establish private trading firms in India, a deregulating act was passed in 1694.[40]

This allowed any English firm to trade with India, unless specifically prohibited by act of parliament, thereby annulling the charter that had been in force for almost 100 years. By an act that was passed in 1698, a new "parallel" East India Company (officially titled the English Company Trading to the East Indies) was floated under a state-backed indemnity of £2 million. The powerful stockholders of the old company quickly subscribed a sum of £315,000 in the new concern, and dominated the new body. The two companies wrestled with each other for some time, both in England and in India, for a dominant share of the trade.[40]

It quickly became evident that, in practice, the original company faced scarcely any measurable competition. The companies merged in 1708, by a tripartite indenture involving both companies and the state, with the charter and agreement for the new United Company of Merchants of England Trading to the East Indies being awarded by the Sidney Godolphin, 1st Earl of Godolphin [41]. Under this arrangement, the merged company lent to the Treasury a sum of £3,200,000, in return for exclusive privileges for the next three years, after which the situation was to be reviewed. The amalgamated company became the United Company of Merchants of England Trading to the East Indies.[40]

Company painting depicting an official of the East India Company, c. 1760

In the following decades there was a constant battle between the company lobby and the Parliament. The company sought a permanent establishment, while the Parliament would not willingly allow it greater autonomy and so relinquish the opportunity to exploit the company's profits. In 1712, another act renewed the status of the company, though the debts were repaid. By 1720, 15% of British imports were from India, almost all passing through the company, which reasserted the influence of the company lobby. The licence was prolonged until 1766 by yet another act in 1730.

At this time, Britain and France became bitter rivals. Frequent skirmishes between them took place for control of colonial possessions. In 1742, fearing the monetary consequences of a war, the British government agreed to extend the deadline for the licensed exclusive trade by the company in India until 1783, in return for a further loan of £1 million. Between 1756 and 1763, the Seven Years' War diverted the state's attention towards consolidation and defence of its territorial possessions in Europe and its colonies in North America.[42]

The war took place on Indian soil, between the company troops and the French forces. In 1757, the Law Officers of the Crown delivered the Pratt-Yorke opinion distinguishing overseas territories acquired by right of conquest from those acquired by private treaty. The opinion asserted that, while the Crown of Great Britain enjoyed sovereignty over both, only the property of the former was vested in the Crown.[42]

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, Britain surged ahead of its European rivals. Demand for Indian commodities was boosted by the need to sustain the troops and the economy during the war, and by the increased availability of raw materials and efficient methods of production. As home to the revolution, Britain experienced higher standards of living. Its spiralling cycle of prosperity, demand and production had a profound influence on overseas trade. The company became the single largest player in the British global market. William Henry Pyne notes in his book The Microcosm of London (1808) that:

On the 1 March 1801, the debts of the East India Company to £5,393,989 their effects to £15,404,736 and their sales increased since February 1793, from £4,988,300 to £7,602,041.

Saltpetre trade

Saltpetre used for gunpowder was one of the major trade goods of the company.

Sir John Banks, a businessman from Kent who negotiated an agreement between the king and the company, began his career in a syndicate arranging contracts for victualling the navy, an interest he kept up for most of his life. He knew that Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn had amassed a substantial fortune from the Levant and Indian trades.

He became a Director and later, as Governor of the East India Company in 1672, he arranged a contract which included a loan of £20,000 and £30,000 worth of saltpetre—also known as potassium nitrate, a primary ingredient in gunpowder—for the King "at the price it shall sell by the candle"—that is by auction—where bidding could continue as long as an inch-long candle remained alight.[43]

Outstanding debts were also agreed and the company permitted to export 250 tons of saltpetre. Again in 1673, Banks successfully negotiated another contract for 700 tons of saltpetre at £37,000 between the king and the company. So urgent was the need to supply the armed forces in the United Kingdom, America and elsewhere that the authorities sometimes turned a blind eye on the untaxed sales. One governor of the company was even reported as saying in 1864 that he would rather have the saltpetre made than the tax on salt.[44]

Basis for the monopoly

Colonial monopoly

An East India Company coin, struck in 1835

Robert Clive became the first British Governor of Bengal after he had instated Mir Jafar as the Nawab of Bengal.

The Seven Years' War (1756–63) resulted in the defeat of the French forces, limited French imperial ambitions, and stunted the influence of the Industrial Revolution in French territories. Robert Clive, the Governor General, led the company to a victory against Joseph François Dupleix, the commander of the French forces in India, and recaptured Fort St George from the French. The company took this respite to seize Manila in 1762.[45][better source needed]

By the Treaty of Paris, France regained the five establishments captured by the British during the war (Pondichéry, Mahe, Karikal, Yanam and Chandernagar) but was prevented from erecting fortifications and keeping troops in Bengal (art. XI). Elsewhere in India, the French were to remain a military threat, particularly during the War of American Independence, and up to the capture of Pondichéry in 1793 at the outset of the French Revolutionary Wars without any military presence. Although these small outposts remained French possessions for the next two hundred years, French ambitions on Indian territories were effectively laid to rest, thus eliminating a major source of economic competition for the company.

In its first century and half, the EIC used a few hundred soldiers as guards. The great expansion came after 1750, when it had 3,000 regular troops. By 1763, it had 26,000; by 1778, it had 67,000. It recruited largely Indian troops, and trained them along European lines.[46] The military arm of the East India Company quickly developed to become a private corporate armed force, and was used as an instrument of geo-political power and expansion, rather than its original purpose as a guard force, and became the most powerful military force in the Indian subcontinent. As it increased in size the army was divided into the Presidency Armies of Bengal, Madras and Bombay each recruiting their own infantry, cavalry, and artillery units. The navy also grew significantly, vastly expanding its fleet and although made up predominantly of heavily armed merchant vessels, called East Indiamen, it also included warships.

Expansion and conquest

The company, fresh from a colossal victory, and with the backing of its own private well-disciplined and experienced army, was able to assert its interests in the Carnatic region from its base at Madras and in Bengal from Calcutta, without facing any further obstacles from other colonial powers.[47]

The Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II, who with his allies fought against the East India Company during his early years (1760–64), only accepting the protection of the British in the year 1803, after he had been blinded by his enemies and deserted by his subjects

It continued to experience resistance from local rulers during its expansion. Robert Clive led company forces against Siraj Ud Daulah, the last independent Nawab of Bengal, Bihar, and Midnapore district in Odisha to victory at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, resulting in the conquest of Bengal. This victory estranged the British and the Mughals, since Siraj Ud Daulah was a Mughal feudatory ally.

With the gradual weakening of the Marathas in the aftermath of the three Anglo-Maratha wars, the British also secured the Ganges-Jumna Doab, the Delhi-Agra region, parts of Bundelkhand, Broach, some districts of Gujarat, the fort of Ahmmadnagar, province of Cuttack (which included Mughalbandi/the coastal part of Odisha, Garjat/the princely states of Odisha, Balasore Port, parts of Midnapore district of West Bengal), Bombay (Mumbai) and the surrounding areas, leading to a formal end of the Maratha empire and firm establishment of the British East India Company in India.

Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, the rulers of the Kingdom of Mysore, offered much resistance to the British forces. Having sided with the French during the Revolutionary War, the rulers of Mysore continued their struggle against the company with the four Anglo-Mysore Wars. Mysore finally fell to the company forces in 1799, in the fourth Anglo-Mysore war during which Tipu Sultan was killed.

Battle of Assaye during the Second Anglo-Maratha War. Company replaced the Marathas as Mughal's protectors after the second Anglo-Maratha war.[48]

The fall of Tipu Sultan and the Sultanate of Mysore, during the Battle of Seringapatam in 1799

The last vestiges of local administration were restricted to the northern regions of Delhi, Oudh, Rajputana, and Punjab, where the company's presence was ever increasing amidst infighting and offers of protection among the remaining princes. The hundred years from the Battle of Plassey in 1757 to the Indian Rebellion of 1857 were a period of consolidation for the company, during which it seized control of the entire Indian subcontinent and functioned more as an administrator and less as a trading concern.

A cholera pandemic began in Bengal, then spread across India by 1820. 10,000 British troops and countless Indians died during this pandemic.[49] Between 1760 and 1834 only some 10% of the East India Company's officers survived to take the final voyage home.[50]

In the early 19th century the Indian question of geopolitical dominance and empire holding remained with the East India Company.[Note 1] The three independent armies of the company's Presidencies, with some locally raised irregular forces, expanded to a total of 280,000 men by 1857.[51] The troops were first recruited from mercenaries and low-caste volunteers, but in time the Bengal Army in particular was composed largely of high-caste Hindus and landowning Muslims.

Within the Army British officers, who initially trained at the company's own academy at the Addiscombe Military Seminary, always outranked Indians, no matter how long the Indians' service. The highest rank to which an Indian soldier could aspire was Subadar-Major (or Rissaldar-Major in cavalry units), effectively a senior subaltern equivalent. Promotion for both British and Indian soldiers was strictly by seniority, so Indian soldiers rarely reached the commissioned ranks of Jamadar or Subadar before they were middle aged at best. They received no training in administration or leadership to make them independent of their British officers.

During the wars against the French and their allies in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the East India Company's armies were used to seize the colonial possessions of other European nations, including the islands of Réunion and Mauritius.

There was a systemic disrespect in the company for the spreading of Protestantism, although it fostered respect for Hindu and Muslim, castes, and ethnic groups. The growth of tensions between the EIC and the local religious and cultural groups grew in the 19th century as the Protestant revival grew in Great Britain. These tensions erupted at the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and the company ceased to exist when the company dissolved through the East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act 1873.[52]

Opium trade

The Nemesis destroying Chinese war junks during the Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841, by Edward Duncan

In the 18th century, Britain had a huge trade deficit with Qing dynasty China and so, in 1773, the company created a British monopoly on opium buying in Bengal, India, by prohibiting the licensing of opium farmers and private cultivation. The monopoly system established in 1799 continued with minimal changes until 1947.[53]

As the opium trade was illegal in China, Company ships could not carry opium to China. So the opium produced in Bengal was sold in Calcutta on condition that it be sent to China.[54]

Despite the Chinese ban on opium imports, reaffirmed in 1799 by the Jiaqing Emperor, the drug was smuggled into China from Bengal by traffickers and agency houses such as Jardine, Matheson & Co and Dent & Co. in amounts averaging 900 tons a year. The proceeds of the drug-smugglers landing their cargoes at Lintin Island were paid into the company's factory at Canton and by 1825, most of the money needed to buy tea in China was raised by the illegal opium trade.

The company established a group of trading settlements centred on the Straits of Malacca called the Straits Settlements in 1826 to protect its trade route to China and to combat local piracy. The settlements were also used as penal settlements for Indian civilian and military prisoners.

In 1838 with the amount of smuggled opium entering China approaching 1,400 tons a year, the Chinese imposed a death penalty for opium smuggling and sent a Special Imperial Commissioner, Lin Zexu, to curb smuggling. This resulted in the First Opium War (1839–42). After the war Hong Kong island was ceded to Britain under the Treaty of Nanking and the Chinese market opened to the opium traders of Britain and other nations.[53] The Jardines and Apcar and Company dominated the trade, although P&O also tried to take a share.[55] A Second Opium War fought by Britain and France against China lasted from 1856 until 1860 and led to the Treaty of Tientsin, which legalised the importation of opium. Legalisation stimulated domestic Chinese opium production and increased the importation of opium from Turkey and Persia. This increased competition for the Chinese market led to India's reducing its opium output and diversifying its exports.[53]

Regulation of the company's affairs

Writers

The Destruction of Tea at Boston Harbor, 1773

The company employed many junior clerks, known as "writers", to record the details of accounting, managerial decisions, and activities related to the company, such as minutes of meetings, copies of Company orders and contracts, and filings of reports and copies of ship's logs. Several well-known British scholars and literary men had Company writerships, such as Henry Thomas Colebrooke in India and Charles Lamb in England. One Indian writer of some importance in the 19th century was Ram Mohan Roy, who learned English, Sanskrit, Persian, Arabic, Greek, and Latin.[56]

Financial troubles

Though the company was becoming increasingly bold and ambitious in putting down resisting states, it was becoming clearer that the company was incapable of governing the vast expanse of the captured territories. The Bengal famine of 1770, in which one-third of the local population died, caused distress in Britain. Military and administrative costs mounted beyond control in British-administered regions in Bengal because of the ensuing drop in labour productivity.

At the same time, there was commercial stagnation and trade depression throughout Europe. The directors of the company attempted to avert bankruptcy by appealing to Parliament for financial help. This led to the passing of the Tea Act in 1773, which gave the company greater autonomy in running its trade in the American colonies, and allowed it an exemption from tea import duties which its colonial competitors were required to pay.

When the American colonists and tea merchants were told of this Act, they boycotted the company tea. Although the price of tea had dropped because of the Act, it also validated the Townshend Acts, setting the precedent for the king to impose additional taxes in the future. The arrival of tax-exempt Company tea, undercutting the local merchants, triggered the Boston Tea Party in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, one of the major events leading up to the American Revolution.

Regulating Acts of Parliament

East India Company Act 1773

By the Regulating Act of 1773 (later known as the East India Company Act 1773), the Parliament of Great Britain imposed a series of administrative and economic reforms; this clearly established Parliament's sovereignty and ultimate control over the company. The Act recognised the company's political functions and clearly established that the "acquisition of sovereignty by the subjects of the Crown is on behalf of the Crown and not in its own right".

Nawab Mubarak Ali Khan with his son in the Nawab's Durbar with British Resident, Sir John Hadley

Despite stiff resistance from the East India lobby in parliament and from the company's shareholders, the Act passed. It introduced substantial governmental control and allowed British India to be formally under the control of the Crown, but leased back to the company at £40,000 for two years. Under the Act's most important provision, a governing Council composed of five members was created in Calcutta. The three members nominated by Parliament and representing the Government's interest could, and invariably would, outvote the two Company members. The Council was headed by Warren Hastings, the incumbent Governor, who became the first Governor-General of Bengal, with an ill-defined authority over the Bombay and Madras Presidencies.[57] His nomination, made by the Court of Directors, would in future be subject to the approval of a Council of Four appointed by the Crown. Initially, the Council consisted of Lt. General Sir John Clavering, The Honourable Sir George Monson, Sir Richard Barwell, and Sir Philip Francis.[58]

Hastings was entrusted with the power of peace and war. British judges and magistrates would also be sent to India to administer the legal system. The Governor General and the council would have complete legislative powers. The company was allowed to maintain its virtual monopoly over trade in exchange for the biennial sum and was obligated to export a minimum quantity of goods yearly to Britain. The costs of administration were to be met by the company. The company initially welcomed these provisions, but the annual burden of the payment contributed to the steady decline of its finances.[58]

East India Company Act 1784 (Pitt's India Act)

The East India Company Act 1784 (Pitt's India Act) had two key aspects:

- Relationship to the British government: the bill differentiated the East India Company's political functions from its commercial activities. In political matters the East India Company was subordinated to the British government directly. To accomplish this, the Act created a Board of Commissioners for the Affairs of India, usually referred to as the Board of Control. The members of the Board were the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Secretary of State, and four Privy Councillors, nominated by the King. The act specified that the Secretary of State "shall preside at, and be President of the said Board".

- Internal Administration of British India: the bill laid the foundation for the centralised and bureaucratic British administration of India which would reach its peak at the beginning of the 20th century during the governor-generalship of George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Baron Curzon.

Pitt's Act was deemed a failure because it quickly became apparent that the boundaries between government control and the company's powers were nebulous and highly subjective. The government felt obliged to respond to humanitarian calls for better treatment of local peoples in British-occupied territories. Edmund Burke, a former East India Company shareholder and diplomat, was moved to address the situation and introduced a new Regulating Bill in 1783. The bill was defeated amid lobbying by company loyalists and accusations of nepotism in the bill's recommendations for the appointment of councillors.

Act of 1786

General Lord Cornwallis, receiving two of Tipu Sultan's sons as hostages in the year 1793

The Act of 1786 (26 Geo. 3 c. 16) enacted the demand of Earl Cornwallis that the powers of the Governor-General be enlarged to empower him, in special cases, to override the majority of his Council and act on his own special responsibility. The Act enabled the offices of the Governor-General and the Commander-in-Chief to be jointly held by the same official.

This Act clearly demarcated borders between the Crown and the company. After this point, the company functioned as a regularised subsidiary of the Crown, with greater accountability for its actions and reached a stable stage of expansion and consolidation. Having temporarily achieved a state of truce with the Crown, the company continued to expand its influence to nearby territories through threats and coercive actions. By the middle of the 19th century, the company's rule extended across most of India, Burma, Malaya, Singapore, and British Hong Kong, and a fifth of the world's population was under its trading influence. In addition, Penang, one of the states in Malaya, became the fourth most important settlement, a presidency, of the company's Indian territories.[59]

East India Company Act 1793 (Charter Act)

The company's charter was renewed for a further 20 years by the Charter Act of 1793. In contrast with the legislative proposals of the previous two decades, the 1793 Act was not a particularly controversial measure, and made only minimal changes to the system of government in India and to British oversight of the company's activities. Sale of liquor was forbidden without licence. It was pointed that the payment of the staff of the board of council should not be made from the Indian revenue.

East India Company Act 1813 (Charter Act)

Major-General Wellesley, meeting with Nawab Azim al-Daula, 1805

The aggressive policies of Lord Wellesley and the Marquess of Hastings led to the company's gaining control of all India (except for the Punjab and Sindh), and some part of the then kingdom of Nepal under the Sugauli Treaty. The Indian Princes had become vassals of the company. But the expense of wars leading to the total control of India strained the company's finances. The company was forced to petition Parliament for assistance. This was the background to the Charter Act of 1813 which, among other things:

- asserted the sovereignty of the British Crown over the Indian territories held by the company;

- renewed the charter of the company for a further twenty years, but

- deprived the company of its Indian trade monopoly except for trade in tea and the trade with China

- required the company to maintain separate and distinct its commercial and territorial accounts

- opened India to missionaries

Government of India Act 1833

The Industrial Revolution in Britain, the consequent search for markets, and the rise of laissez-faire economic ideology form the background to the Government of India Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. 4 c. 85). The Act:

- removed the company's remaining trade monopolies and divested it of all its commercial functions

- renewed for another twenty years the company's political and administrative authority

- invested the Board of Control with full power and authority over the company. As stated by Professor Sri Ram Sharma,[60] "The President of the Board of Control now became Minister for Indian Affairs."

- carried further the ongoing process of administrative centralisation through investing the Governor-General in Council with, full power and authority to superintend and, control the Presidency Governments in all civil and military matters

- initiated a machinery for the codification of laws

- provided that no Indian subject of the company would be debarred from holding any office under the company by reason of his religion, place of birth, descent or colour

- vested the Island of St Helena in the Crown[61]

British influence continued to expand; in 1845, Great Britain purchased the Danish colony of Tranquebar. The company had at various stages extended its influence to China, the Philippines, and Java. It had solved its critical lack of cash needed to buy tea by exporting Indian-grown opium to China. China's efforts to end the trade led to the First Opium War (1839–1842).

English Education Act 1835

View of the Calcutta port in 1848

The English Education Act by the Council of India in 1835 reallocated funds from the East India Company to spend on education and literature in India.

Government of India Act 1853

This Act (16 & 17 Vict. c. 95) provided that British India would remain under the administration of the company in trust for the Crown until Parliament should decide otherwise. It also introduced a system of open competition as the basis of recruitment for civil servants of the company and thus deprived the Directors of their patronage system.[62]

Under the act, for the first time the legislative and executive powers of the governor general's council were separated. It also added six additional members to the governor general's executive committee.[63]

Indian Rebellion and disestablishment

Capture of the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar and his sons by William Hodson in 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 (also known as the Indian Mutiny) resulted in widespread devastation in India: many condemned the East India Company for permitting the events to occur.[64] In the aftermath of the Rebellion, under the provisions of the Government of India Act 1858, the British Government nationalised the company. The Crown took over its Indian possessions, its administrative powers and machinery, and its armed forces.

The company remained in existence in vestigial form, continuing to manage the tea trade on behalf of the British Government (and the supply of Saint Helena) until the East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act 1873 came into effect, on 1 January 1874. This Act provided for the formal dissolution of the company on 1 June 1874, after a final dividend payment and the commutation or redemption of its stock.[65]The Times commented on 8 April 1873:[66]

It accomplished a work such as in the whole history of the human race no other trading Company ever attempted, and such as none, surely, is likely to attempt in the years to come.

In the 1980s, a group of investors purchased the rights to the moribund corporate brand and founded a clothing company, which lasted until the 1990s. The corporate vestiges were again purchased by another group of investors who opened their first store in 2010.

Establishments in Britain

The expanded East India House, London, painted by Thomas Malton in c.1800

The company's headquarters in London, from which much of India was governed, was East India House in Leadenhall Street. After occupying premises in Philpot Lane from 1600 to 1621; in Crosby House, Bishopsgate, from 1621 to 1638; and in Leadenhall Street from 1638 to 1648, the company moved into Craven House, an Elizabethan mansion in Leadenhall Street. The building had become known as East India House by 1661. It was completely rebuilt and enlarged in 1726–9; and further significantly remodelled and expanded in 1796–1800. It was finally vacated in 1860 and demolished in 1861–62. The site is now occupied by the Lloyd's building.

In 1607, the company decided to build its own ships and leased a yard on the River Thames at Deptford. By 1614, the yard having become too small, an alternative site was acquired at Blackwall: the new yard was fully operational by 1617. It was sold in 1656, although for some years East India Company ships continued to be built and repaired there under the new owners.

In 1803, an Act of Parliament, promoted by the East India Company, established the East India Dock Company, with the aim of establishing a new set of docks (the East India Docks) primarily for the use of ships trading with India. The existing Brunswick Dock, part of the Blackwall Yard site, became the Export Dock; while a new Import Dock was built to the north. In 1838 the East India Dock Company merged with the West India Dock Company. The docks were taken over by the Port of London Authority in 1909, and closed in 1967.

Addiscombe Seminary, photographed in c.1859, with cadets in the foreground

The East India College was founded in 1806 as a training establishment for "writers" (i.e. clerks) in the company's service. It was initially located in Hertford Castle, but moved in 1809 to purpose-built premises at Hertford Heath, Hertfordshire. In 1858 the college closed; but in 1862 the buildings reopened as a public school, now Haileybury and Imperial Service College.

The East India Company Military Seminary was founded in 1809 at Addiscombe, near Croydon, Surrey, to train young officers for service in the company's armies in India. It was based in Addiscombe Place, an early 18th-century mansion. The government took it over in 1858, and renamed it the Royal Indian Military College. In 1861 it was closed, and the site was subsequently redeveloped.

In 1818, the company entered into an agreement by which those of its servants who were certified insane in India might be cared for at Pembroke House, Hackney, London, a private lunatic asylum run by Dr George Rees until 1838, and thereafter by Dr William Williams. The arrangement outlasted the company itself, continuing until 1870, when the India Office opened its own asylum, the Royal India Asylum, at Hanwell, Middlesex.[67][68]

The East India Club in London was formed in 1849 for officers of the company. The Club still exists today as a private gentlemen's club with its club house situated at 16 St. James's Square, London.[69]

Legacy and criticisms

The East India Company was one of the most powerful and enduring organisations in history and had a long lasting impact on the Indian Subcontinent, with both positive and harmful effects. Although dissolved by the East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act 1873 following the rebellion of 1857, it stimulated the growth of the British Empire. Its armies were to become the armies of British India after 1857, and it played a key role in introducing English as an official language in India. This also led to Macaulayism in the Indian subcontinent.

Once the East India Company took over Bengal in the treaty of Allahabad (1765) it collected taxes which it used to further its expansion to the rest of India and did not have to rely on venture capital from London. It returned a high profit to those who risked original money for earlier ventures into Bengal.

During the first century of the East India Company’s expansion in India, most people in India lived under regional kings or Nawabs. By the late 18th century many Moghuls were weak in comparison to the rapidly expanding Company as it took over cities and land, built railways, roads and bridges. The first railway of 21 mile (33.8 km),[70] known as the Great Indian Peninsula Railway ran between Bombay (Mumbai) and Tannah (Thane) in 1849. The Company sought quick profits because the financial backers in England took high risks: their money for possible profits or losses through shipwrecks, wars or calamities.

The increasingly large territory the Company was annexing and collecting taxes was also run by the local Nawabs. In essence, it was a dual administration. Between 1765 and 1772 Robert Clive gave the responsibility of tax collecting, diwani, to the Indian deputy and judicial and police responsibilities to other Indian deputies. The Company concentrated its new power of collecting revenue and left the responsibilities to the Indian agencies. The East India Company took the beginning steps of British takeover of power in India for centuries to come. In 1772 the Company made Warren Hastings, who had been in India with the Company since 1750, its first governor general to manage and overview all of the annexed lands. The dual administration system came to an end.

Hastings learned Urdu and Persian and took great interest in preserving ancient Sanskrit manuscripts and having them translated into English. He employed many Indians as officials.[71]

Hastings used Sanskrit texts for Hindus and Arabic texts for Muslims. This is still used in Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi courts today in civil law. Hastings also annexed lands and kingdoms and enriched himself in the process. His enemies in London used this against him to have him impeached. See (Impeachment of Warren Hastings)[72]

Charles Cornwallis, widely remembered as having surrendered to George Washington in 1781, replaced Hastings. Cornwallis distrusted Indians and replaced Indians with English. He introduced a system of personal land ownership for Indians. This change caused much conflict since most illiterate people had no idea why they suddenly became land owners to land renters.[73]

Mughals often had to choose to fight against the Company and lose everything or cooperate with the Company and receive a big pension but lose the throne. The British East India Company gradually took over most of India by threat, intimidation, bribery or outright war.[74]

The East India Company was the first company to record the Chinese usage of orange-flavoured tea, which led to the development of Earl Grey tea.[75]

The East India Company introduced a system of merit-based appointments that provided a model for the British and Indian civil service.[76]

Widespread corruption and looting of Bengal resources and treasures during its rule resulted in poverty.[6] Famines, such as the Great Bengal famine of 1770 and subsequent famines during the 18th and 19th centuries, became more widespread, chiefly because of exploitative agriculture promulgated by the policies of the East India company and the forced cultivation of opium in place of grain.[77][78]

Symbols

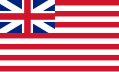

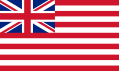

Flags

- Historical depictions

Downman (1685)

Lens (1700)

National Geographic (1917)

Rees (1820)

Laurie (1842)

- Modern depictions

1600–1707

1707–1801

1801–1874

The English East India Company flag changed with history, with a canton based on the current flag of the Kingdom, and a field of 9 to 13 alternating red and white stripes.

From the period of 1600, the canton consisted of a St George's Cross representing the Kingdom of England. With the Acts of Union 1707, the canton was updated to be the new Union Flag—consisting of an English St George's Cross combined with a Scottish St Andrew's cross—representing the Kingdom of Great Britain. After the Acts of Union 1800 that joined Ireland with Great Britain to form the United Kingdom, the canton of the East India Company flag was altered accordingly to include a Saint Patrick's Saltire replicating the updated Union Flag representing the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Regarding the field of the flag, there has been much debate and discussion regarding the number and order of the stripes. Historical documents and paintings show many variations from 9 to 13 stripes, with some images showing the top stripes being red and others showing the top stripe being white.

At the time of the American Revolution the East India Company flag was nearly identical to the Grand Union Flag. Historian Charles Fawcett argued that the East India Company Flag inspired the Stars and Stripes.[79]

Coat of arms

The later coat of arms of the East India Company

The East India Company's original coat of arms was granted in 1600. The blazon of the arms is as follows:

"Azure, three ships with three masts, rigged and under full sail, the sails, pennants and ensigns Argent, each charged with a cross Gules; on a chief of the second a pale quarterly Azure and Gules, on the 1st and 4th a fleur-de-lis or, on the 2nd and 3rd a leopard or, between two roses Gules seeded Or barbed Vert." The shield had as a crest: "A sphere without a frame, bounded with the Zodiac in bend Or, between two pennants flottant Argent, each charged with a cross Gules, over the sphere the words DEUS INDICAT" (Latin: God Indicates). The supporters were two sea lions (lions with fishes' tails) and the motto was DEO DUCENTE NIL NOCET (Latin: Where God Leads, Nothing Harms).[80]

The East India Company's arms, granted in 1698, were: "Argent a cross Gules; in the dexter chief quarter an escutcheon of the arms of France and England quarterly, the shield ornamentally and regally crowned Or." The crest was: "A lion rampant guardant Or holding between the forepaws a regal crown proper." The supporters were: "Two lions rampant guardant Or, each supporting a banner erect Argent, charged with a cross Gules." The motto was AUSPICIO REGIS ET SENATUS ANGLIÆ (Latin: Under the auspices of the King and the Senate of England).[80]

Merchant mark

HEIC Merchant's mark on East India Company Coin: 1791 Half Pice

HEIC Merchant's mark on a Blue Scinde Dawk postage stamp (1852)

When the East India Company was chartered in 1600, it was still customary for individual merchants or members of companies such as the Company of Merchant Adventurers to have a distinguishing merchant's mark which often included the mystical "Sign of Four" and served as a trademark. The East India Company's merchant mark consisted of a "Sign of Four" atop a heart within which was a saltire between the lower arms of which were the initials "EIC". This mark was a central motif of the East India Company's coinage[81] and forms the central emblem displayed on the Scinde Dawk postage stamps.[82]

Ships

Ships in Bombay Harbour, c. 1731

Ships of the East India Company were called East Indiamen or simply "Indiamen".[83]

The East Indiaman Royal George, 1779. Royal George was one of the five East Indiamen the Spanish fleet captured in 1780.

During the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, the East India Company arranged for letters of marque for its vessels such as the Lord Nelson. This was not so that they could carry cannon to fend off warships, privateers, and pirates on their voyages to India and China (that they could do without permission) but so that, should they have the opportunity to take a prize, they could do so without being guilty of piracy. Similarly, the Earl of Mornington, an East India Company packet ship of only six guns, also sailed under a letter of marque.

In addition, the company had its own navy, the Bombay Marine, equipped with warships such as Grappler. These vessels often accompanied vessels of the Royal Navy on expeditions, such as the Invasion of Java.

At the Battle of Pulo Aura, which was probably the company's most notable naval victory, Nathaniel Dance, Commodore of a convoy of Indiamen and sailing aboard the Warley, led several Indiamen in a skirmish with a French squadron, driving them off. Some six years earlier, on 28 January 1797, five Indiamen, the Woodford, under Captain Charles Lennox, the Taunton-Castle, Captain Edward Studd, Canton, Captain Abel Vyvyan, Boddam, Captain George Palmer, and Ocean, Captain John Christian Lochner, had encountered Admiral de Sercey and his squadron of frigates. On this occasion the Indiamen also succeeded in bluffing their way to safety, and without any shots even being fired. Lastly, on 15 June 1795, the General Goddard played a large role in the capture of seven Dutch East Indiamen off St Helena.

East Indiamen were large and strongly built and when the Royal Navy was desperate for vessels to escort merchant convoys it bought several of them to convert to warships. Earl of Mornington became HMS Drake. Other examples include:

- HMS Calcutta (1795)

- HMS Glatton (1795)

- HMS Hindostan (1795)

- HMS Hindostan (1804)

- HMS Malabar (1804)

- HMS Buffalo (1813)

Their design as merchant vessels meant that their performance in the warship role was underwhelming and the Navy converted them to transports.

Records

Unlike all other British Government records, the records from the East India Company (and its successor the India Office) are not in The National Archives at Kew, London, but are held by the British Library in London as part of the Asia, Pacific and Africa Collections. The catalogue is searchable online in the Access to Archives catalogues.[84] Many of the East India Company records are freely available online under an agreement that the Families in British India Society has with the British Library. Published catalogues exist of East India Company ships' journals and logs, 1600–1834;[85] and of some of the company's daughter institutions, including the East India Company College, Haileybury, and Addiscombe Military Seminary.[86]

The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies, first issued in 1816, was sponsored by the East India Company, and includes much information relating to the EIC.

See also

East India Company:

Company rule in India- Economy of India under Company rule

- Governor-General of India

- Chief Justice of Bengal

- Advocate-General of Bengal

- Chief Justice of Madras

- Indian Rebellion of 1857

- Indian independence movement

- List of East India Company directors

- List of trading companies

- East India Company Cemetery in Macau

- Category:Honourable East India Company regiments

General:

- British Imperial Lifeline

- Lascar

- Carnatic Wars

- Commercial Revolution

- Political warfare in British colonial India

- Trade between Western Europe and the Mughal Empire in the 17th century

- Whampoa anchorage

Notes and references

^ As of 30 December 1600, the company's official name was: Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading with the East Indies.

^ Carey, W. H. (1882). 1882 – The Good Old Days of Honourable John Company. Simla: Argus Press. Retrieved 2015-07-30.

^ The Dutch East India Company was the first to issue public stock.

^ ab "Books associated with Trading Places – the East India Company and Asia 1600–1834, an Exhibition". Archived from the original on 30 March 2014.

^ Baladouni, Vahe (Fall 1983). "Accounting in the Early Years of the East India Company". The Accounting Historians Journal. The Academy of Accounting Historians. 10 (2): 63–80. JSTOR 40697780.

^ "India – The British, 1600–1740".

^ abc Dalrymple, William (4 March 2015). "The East India Company: The original corporate raiders". The Guardian. Retrieved 2017-06-08.

^ "The finances of the East India Company in India, c. 1766–1859, John F. Richards".

^ This is the argument of Robins (2006).

^ Desai, Tripta (1984). The East India Company: A Brief Survey from 1599 to 1857. Kanak Publications. p. 3.

^ abcd "Imperial Gazetteer of India". II. 1908: 454.

^ ab Wernham, R.B (1994). The Return of the Armadas: The Last Years of the Elizabethan Wars Against Spain 1595–1603. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 333–34. ISBN 978-0-19-820443-5.

^ ab McCulloch, John Ramsay (1833). A Treatise on the Principles, Practice, & History of Commerce. Baldwin and Cradock. p. 120.

^ Leinwand 2006.

^ 'Ralph Fitch: An Elizabethan Merchant in Chiang Mai; and 'Ralph Fitch's Account of Chiang Mai in 1586–1587' in: Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai Volume 1. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012.

^ Prasad, Ram Chandra (1980). Early English Travellers in India: A Study in the Travel Literature of the Elizabethan and Jacobean Periods with Particular Reference to India. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 45. ISBN 9788120824652.

^ Wilbur, Marguerite Eyer (1945). The East India Company: And the British Empire in the Far East. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-8047-2864-5.

^ ab "East Indies: September 1599". british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-02-18.

^ ab Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. II 1908, p. 6

^ Kerr, Robert (1813). A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels. 8. p. 102.

^ Timbs, John (1855). Curiosities of London: Exhibiting the Most Rare and Remarkable Objects of Interest in the Metropolis. D. Bogue. p. 264.

^ Gardner, Brian (1972). The East India Company: a History. McCall Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8415-0124-6.

^ Dulles (1969), p106.

^ Foster, Sir William. England's quest of eastern trade (1933 ed.). London: A. & C. Black. p. 157.

^ ab East India Company (1897). List of factory records of the late East India Company: preserved in the Record Department of the India Office, London. p. vi.

^ ab James Mill (1817). "1". The History of British India. Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy. pp. 15–18. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

^ ab The battle of Plassey ended the tax on the Indian goods. Indian History Sourcebook: England, India, and The East Indies, 1617 A.D

^ Tyacke, Sarah (2008). "Gabriel Tatton's Maritime Atlas of the East Indies, 1620–1621: Portsmouth Royal Naval Museum, Admiralty Library Manuscript, MSS 352". Imago Mundi. 60 (1): 39–62. doi:10.1080/03085690701669293.

^ "The Nutmeg Wars".

^ ab Suijk, Paul (Director) (2015). 1600 The British East India Company [The Great Courses (Episode 5, 13:16] (on-line video). Brentwood Associates/The Teaching Company Sales. Chantilly, VA, USA: Liulevicius, Professor Vejas Gabriel (lecturer).

^ Suijk, Paul (Director) (2015). 1600 The British East India Company [The Great Courses (Episode 5, 15:18] (on-line video). Brentwood Associates/The Teaching Company Sales. Chantilly, VA, USA: Liulevicius, Professor Vejas Gabriel (lecturer).

^ Riddick, John F. (2006). The history of British India: a chronology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 4. ISBN 0-313-32280-5.

^ "East India Company" (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, Volume 8, p.835

^ "Asia facts, information, pictures – Encyclopedia.com articles about Asia". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

^ Broadberry, Stephen; Gupta, Bishnupriya. "The Rise, Organization, and Institutional Framework of Factor Markets,". International Institute of Social history. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

^ Wilbur, Marguerite Eyer (1945). The East India Company: And the British Empire in the Far East. Stanford University Press. pp. 82–3. ISBN 978-0-8047-2864-5.

^ Hayami, Akira (2015). Japan's Industrious Revolution: Economic and Social Transformations in the Early Modern Period. Springer. p. 49. ISBN 978-4-431-55142-3.

^ Burgess, Douglas R (2009). The Pirates' Pact: The Secret Alliances Between History's Most Notorious Buccaneers and Colonial America. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-147476-4.

^ Burgess 2009, p. 144

^ Fox, E. T. (2008). King of the Pirates: The Swashbuckling Life of Henry Every. London: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-4718-6.

^ abc "The British East India Company—the Company that Owned a Nation. George P. Landow".

^ Company, East India; Shaw, John (1887). Charters Relating to the East India Company from 1600 to 1761: Reprinted from a Former Collection with Some Additions and a Preface for the Government of Madras. R. Hill at the Government Press. p. 217.

^ ab Thomas, P. D. G. (2008) "Pratt, Charles, first Earl Camden (1714–1794)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, online edn. Retrieved 15 February 2008 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

^ Janssens, Koen (2009). Annales Du 17e Congrès D'Associationi Internationale Pour L'histoire Du Verre. Asp / Vubpress / Upa. p. 366. ISBN 978-90-5487-618-2.

^ "SALTPETER the secret salt – Salt made the world go round". salt.org.il. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

^ "The Seven Years' War in the Philippines". Land Forces of Britain, the Empire and Commonwealth. Archived from the original on 10 July 2004. Retrieved 2013-09-04.

^ Gerald Bryant (1978). "Officers of the East India Company's army in the days of Clive and Hastings". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 6 (3): 203–27. doi:10.1080/03086537808582508.

^ James Stuart Olson; Robert Shadle (1996). Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. Greenwood. pp. 252–54. ISBN 978-0-313-29366-5.

^ Capper, John (7 July 2017). "Delhi, the Capital of India". Asian Educational Services. p. 28. ISBN 978-81-206-1282-2.

^ "Cholera's seven pandemics". CBC News. 2 December 2008. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 2016-03-07.

^ Holmes, Richard (2005). Sahib: the British soldier in India, 1750–1914. London: HarperCollins. p. 474. ISBN 0-00-713753-2.

^ McElwee, William (1974). The Art of War: Waterloo to Mons. Purnell Book Services. p. 72.

^ Tolan, John; Veinstein, Gilles; Henry Laurens (2013). "Europe and the Islamic World: A History". Princeton University Press. pp. 275–276. ISBN 978-0-691-14705-5.

^ abc Windle, James (2012). "Insights for Contemporary Drug Policy: A Historical Account of Opium Control in India and Pakistan". Asian Journal of Criminology. 7 (1): 55–74. doi:10.1007/s11417-011-9104-0.

^ "EAST INDIA COMPANY FACTORY RECORDS Sources from the British Library, LondonPart 1: China and Japan". ampltd.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

^ Harcourt, Freda (2006). Flagships of Imperialism: The P & O Company and the Politics of Empire from Its Origins to 1867. Manchester University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-84779-145-0.

^ Suijk, Paul (Director) (2015). The British East India Company [The Great Courses (Episode 24, 7:38-4:33)] (on-line video). Brentwood Associates/The Teaching Company Sales. Chantilly, VA, USA: Fisher, Professor Michael H (lecturer).

^ Keay, John (1991). The Honourable Company: A History of the English East India Company. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York p. 385.

^ ab Anthony, Frank. Britain's Betrayal in India: The Story of the Anglo Indian Community. Second Edition. London: The Simon Wallenberg Press, 2007 Pages 18–19, 42, 45.

^ Langdon, Marcus; "Penang: The Fourth Presidency of India 1805–1830, Volume One: Ships, Men and Mansions", Areca Books, 2013. ISBN 978-967-5719-07-3

^ "Kapur".

^ "Saint Helena Act 1833". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

^ M. Laxhimikanth, Public Administration, TMH, Tenth Reprint, 2013

^ Laxhimikanth, Public Administration, TMH, Tenth Reprint, 2013

^ David, Saul (4 September 2003). The Indian Mutiny: 1857 (4th ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-100554-8.

^ East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act 1873 (36 & 37 Vict. 17) s. 36: "On the First day of June One thousand eight hundred and seventy-four, and on payment by the East India Company of all unclaimed dividends on East India Stock to such accounts as are herein-before mentioned in pursuance of the directions herein-before contained, the powers of the East India Company shall cease, and the said Company shall be dissolved." Where possible, the stock was redeemed through commutation (i.e. exchanging the stock for other securities or money) on terms agreed with the stockholders (ss. 5–8), but stockholders who did not agree to commute their holdings had their stock compulsorily redeemed on 30 April 1874 by payment of £200 for every £100 of stock held (s. 13).

^ "Not many days ago the House of Commons passed". Times. London. 8 April 1873. p. 9.

^ Farrington 1976, pp. 125–32.

^ Bolton, Diane K.; Croot, Patricia E. C.; Hicks, M. A. (1982). "Ealing and Brentford: Public services". In Baker, T. F. T.; Elrington, C. R. A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 7, Acton, Chiswick, Ealing and Brentford, West Twyford, Willesden. London: Victoria County History. pp. 147–149.

^ "East India Club".

^ Rao, M.A. (1988). Indian Railways, New Delhi: National Book Trust, p.15

^ Suijk, Paul (Director) (2015). The British East India Company [The Great Courses (Episode 24,19:11)] (on-line video). Brentwood Associates/The Teaching Company Sales. Chantilly, VA, USA: Fisher, Professor Michael H (lecturer).

^ Suijk, Paul (Director) (2015). The British East India Company [The Great Courses (Episode 24,17:27)] (on-line video). Brentwood Associates/The Teaching Company Sales. Chantilly, VA, USA: Fisher, Professor Michael H (lecturer).