Neil Simon

| Neil Simon | |

|---|---|

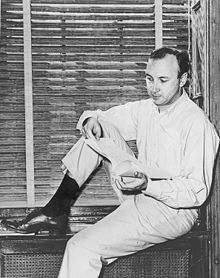

Neil Simon in 1974 | |

| Born | Marvin Neil Simon (1927-07-04)July 4, 1927 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | August 26, 2018(2018-08-26) (aged 91) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Playwright, screenwriter, author |

| Alma mater | New York University[1] University of Denver[1] |

| Spouse | Joan Baim (m. 1953; d. 1973) Marsha Mason (m. 1973; div. 1983) Diane Lander (m. 1987; div. 1988) (m. 1990; div. 1998) Elaine Joyce (m. 1999; his death 2018) |

| Children | 3 |

| Information | |

| Period | 1948–2010 |

| Genre | Comedy, drama, farce, autobiography |

| Notable work(s) | Brighton Beach Memoirs Biloxi Blues Come Blow Your Horn The Odd Couple Lost in Yonkers |

| Awards | Pulitzer Prize for Drama (1991) |

Marvin Neil Simon (July 4, 1927 – August 26, 2018) was an American playwright, screenwriter and author. He wrote more than 30 plays and nearly the same number of movie screenplays, mostly adaptations of his plays. He received more combined Oscar and Tony nominations than any other writer.[2]

Simon grew up in New York City during the Great Depression, with his parents' financial hardships affecting their marriage, giving him a mostly unhappy and unstable childhood. He often took refuge in movie theaters where he enjoyed watching the early comedians like Charlie Chaplin. After a few years in the Army Air Force Reserve, and after graduating from high school, he began writing comedy scripts for radio and some popular early television shows. Among them were Sid Caesar's Your Show of Shows from 1950 (where he worked alongside other young writers including Carl Reiner, Mel Brooks and Selma Diamond), and The Phil Silvers Show, which ran from 1955 to 1959.

He began writing his own plays beginning with Come Blow Your Horn (1961), which took him three years to complete and ran for 678 performances on Broadway. It was followed by two more successful plays, Barefoot in the Park (1963) and The Odd Couple (1965), for which he won a Tony Award. It made him a national celebrity and "the hottest new playwright on Broadway."[3] During the 1960s to 1980s, he wrote both original screenplays and stage plays, with some films actually based on his plays. His style ranged from romantic comedy to farce to more serious dramatic comedy. Overall, he garnered 17 Tony nominations and won three. During one season, he had four successful plays running on Broadway at the same time, and in 1983 became the only living playwright to have a New York theatre, the Neil Simon Theatre, named in his honor.

Contents

1 Early years

2 Writing career

2.1 Television comedy

2.2 Playwright

2.3 Screenwriter

3 Themes and genres

4 Characters

5 Style and subject matter

6 Critical response

7 Personal life

8 Honors and recognition

9 Awards

10 Work

10.1 Theatre

10.2 Screenplays

10.3 Television

10.3.1 Television series

10.3.2 Movies made for television

10.4 Bibliography

11 Notes

12 References

13 External links

Early years

Neil Simon was born on July 4, 1927, in The Bronx, New York, to Jewish parents. His father, Irving Simon, was a garment salesman, and his mother, Mamie (Levy) Simon, was mostly a homemaker.[4] Simon had one older brother by eight years, television writer and comedy teacher Danny Simon. He grew up in Washington Heights, Manhattan, during the period of the Great Depression, graduating from DeWitt Clinton High School when he was sixteen, where he was nicknamed "Doc" and described as extremely shy in the school yearbook.[5]:39

Simon's childhood was difficult and mostly unhappy due to his parents' "tempestuous marriage" and financial hardship caused by the Depression.[3]:1 He would sometimes block out their arguments by putting a pillow over his ears at night.[6] His father often abandoned the family for months at a time, causing them further financial and emotional hardship. As a result, Simon and his brother Danny were sometimes forced to live with different relatives, or else their parents took in boarders for some income.[3]:2

During an interview with writer Lawrence Grobel, Simon stated: "To this day I never really knew what the reason for all the fights and battles were about between the two of them ... She'd hate him and be very angry, but he would come back and she would take him back. She really loved him."[7]:378 Simon states that among the reasons he became a writer was to fulfill his need to be independent of such emotional family issues, a need he recognized when he was seven or eight: "I'd better start taking care of myself somehow ... It made me strong as an independent person.[7]:378

To escape difficulties at home he often took refuge in movie theaters, where he especially enjoyed comedies with silent stars like Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Laurel and Hardy. Simon recalls: "I was constantly being dragged out of movies for laughing too loud."

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

I think part of what made me a comedy writer is the blocking out of some of the really ugly, painful things in my childhood and covering it up with a humorous attitude ... do something to laugh until I was able to forget what was hurting.[3]:2

Simon acknowledged these childhood movies as having inspired him to write comedy: "I wanted to make a whole audience fall onto the floor, writhing and laughing so hard that some of them pass out."[8]:1 He appreciated Chaplin's ability to make people laugh and made writing comedy his long-term goal, and also saw it as a way to connect with people. "I was never going to be an athlete or a doctor."[7]:379 He began creating comedy for which he got paid while still in high school, when at the age of fifteen, Simon and his brother created a series of comedy sketches for employees at an annual department store event. And to help develop his writing skill, he often spent three days a week at the library reading books by famous humorists such as Mark Twain, Robert Benchley, George S. Kaufman and S. J. Perelman.[5]:218

Soon after graduating from high school, he signed up with the Army Air Force Reserve at New York University, and was eventually sent to Colorado as a corporal. It was during those years in the Reserve that Simon began writing, starting as a sports editor. He was assigned to Lowry Air Force Base during 1945 and attended the University of Denver[1] from 1945 to 1946.[1][3]:2

Writing career

Television comedy

Simon in 1966

Simon quit his job as a mailroom clerk in the Warner Brothers offices in Manhattan to write radio and television scripts with his brother Danny Simon, including tutelage by radio humourist Goodman Ace when Ace ran a short-lived writing workshop for CBS. They wrote for the radio series The Robert Q. Lewis Show, which led to other writing jobs. Max Liebman hired the duo for his popular television comedy series Your Show of Shows, for which he earned two Emmy Award nominations. He later wrote scripts for The Phil Silvers Show; the episodes were broadcast during 1958 and 1959.

Simon credited these two latter writing jobs for their importance to his career, having stated that "between the two of them, I spent five years and learned more about what I was eventually going to do than in any other previous experience."[7]:381 He added, "I knew when I walked into Your Show of Shows, that this was the most talented group of writers that up until that time had ever been assembled together."[2] Simon described a typical writing session with the show:[9]

There were about seven writers, plus Sid, Carl Reiner, and Howie Morris ... Mel Brooks and maybe Woody Allen would write one of the other sketches ... everyone would pitch in and rewrite, so we all had a part of it ... It was probably the most enjoyable time I ever had in writing with other people.[7]:382

Simon incorporated some of their experiences into his play Laughter on the 23rd Floor (1993). A 2001 TV adaptation of the play won him two Emmy Award nominations. The first Broadway show Simon wrote for was Catch a Star! (1955), collaborating on sketches with his brother, Danny.[10][11]

Playwright

During 1961, Simon's first Broadway play, Come Blow Your Horn, ran for 678 performances at the Brooks Atkinson Theatre. Simon took three years to write that first play, partly because he was also working on writing television scripts. He rewrote the play at least twenty times from beginning to end:[7]:384 "It was the lack of belief in myself. I said, 'This isn't good enough. It's not right.' ... It was the equivalent of three years of college."[7]:384 That play, besides being a "monumental effort" for Simon, was a turning point in his career: "The theater and I discovered each other."[12]:3

With Cy Coleman at piano rehearsing, 1982

After Barefoot in the Park (1963) and The Odd Couple (1965), for which he won a Tony Award, he became a national celebrity and was considered "the hottest new playwright on Broadway", writes Susan Koprince in her book on Simon.[3]:3 Those successful productions were followed by others. During 1966, Simon had four shows playing at Broadway theatres simultaneously: Sweet Charity,[13]The Star-Spangled Girl,[14]The Odd Couple[15] and Barefoot in the Park.[16] His professional association with producer Emanuel Azenberg began with The Sunshine Boys and continued with The Good Doctor, God's Favorite, Chapter Two, They're Playing Our Song, I Ought to Be in Pictures, Brighton Beach Memoirs, Biloxi Blues, Broadway Bound, Jake's Women, The Goodbye Girl and Laughter on the 23rd Floor, among others.[17] His subjects ranged from serious to romantic comedy to more serious drama and less humor. Overall, he garnered seventeen Tony nominations and won three.[18]

Simon also adapted material written by others for his plays, such as the musical Little Me (1962) from the novel by Patrick Dennis, Sweet Charity (1966) from a screenplay by Federico Fellini and others (for Nights of Cabiria, 1957), and Promises, Promises (1968) from a film by Billy Wilder, The Apartment. Simon was occasionally brought in as an uncredited "script doctor" to help hone the book for Broadway-bound plays or musicals under development[19] such as A Chorus Line (1975).[20] During the 1970s, he wrote a string of successful plays, sometimes having more than one playing at the same time to standing room only audiences. And while he was by then recognized as one of the country's leading playwrights, his inner drive kept him writing:

Did I relax and watch my boyhood ambitions being fulfilled before my eyes? Not if you were born in the Bronx, in the Depression and Jewish, you don't.[5]:47

Simon also drew "extensively on his own life and experience" for his stories, with settings typically in working-class New York City neighborhoods, similar to ones in which he grew up. In 1983, he began writing the first of three autobiographical plays, Brighton Beach Memoirs (1983), Biloxi Blues (1985) and Broadway Bound (1986). With them, he received his greatest critical acclaim. After his follow-up play, Lost in Yonkers (1991), Simon was awarded a Pulitzer Prize.[2]

Screenwriter

Simon also wrote screenplays for more than twenty films, and he received four Academy Award nominations for his screenplays. Some of his screenplays are adaptations of his own plays, along with some original work, including The Out-of-Towners, Murder by Death and The Goodbye Girl. Although most of his films were successful, movies were always secondary in importance to him to his plays:[7]:372

I always feel more like a writer when I'm writing a play, because of the tradition of the theater ... there is no tradition of the screenwriter, unless he is also the director, which makes him an auteur. So I really feel that I'm writing for posterity with plays, which have been around since the Greek times.[7]:375

Simon chose not to write the screenplay for the first film adaptation of his work, Come Blow Your Horn (1963), preferring to focus on his playwriting. However, he was disappointed with the film, and tried to control his film screenplays thereafter. Many of his earlier screenplays were similar to the play, a characteristic Simon observed in hindsight: "I really didn't have an interest in films then", he explains. "I was mainly interested in continuing writing for the theater ... The plays never became cinematic".[3]:153The Odd Couple (1968), however, was a highly successful early adaptation, both faithful to the stage play, but also opened out, having more scenic variety.[21]

Themes and genres

Theater critic John Lahr describes Simon's primary theme as being about "the silent majority", many of whom are "frustrated, edgy, and insecure". Simon's characters are also portrayed as "likable" and easy for audiences to identify with, often having difficult relationships in marriage, friendship or business, as they "struggle to find a sense of belonging".[3]:5 There is always "an implied seeking for solutions to human problems through relationships with other people [and] Simon is able to deal with serious topics of universal and enduring concern", writes biographer Edythe McGovern, while still making people laugh.[12]:11

She adds that one of Simon's hallmarks is his "great compassion for his fellow human beings,"[12]:188 an opinion similar to that of author Alan Cooper, who states that Simon's plays "are essentially about friendships, even when they are about marriage or siblings or crazy aunts ..."[5]:46

Many of Simon's plays are set in New York City, which gives them an urban flavor. Within that setting, Simon's themes, besides marital conflict, sometimes include infidelity, sibling rivalry, adolescences, bereavement, and fear of aging. And despite the serious nature of the themes, Simon continually managed to tell the stories with humor, developing the theme to include both realism and comedy.[3]:11 Simon said he would tell aspiring comedy playwrights "not to try to make it funny ... try and make it real and then the comedy will come."[5]:232

"When I was writing plays," he says, "I was almost always (with some exceptions) writing a drama that was funny ... I wanted to tell a story about real people."[5]:219 Simon explained how he managed this combination:

My view is, "how sad and funny life is." I can't think of a humorous situation that does not involve some pain. I used to ask, "What is a funny situation?" Now I ask, "What is a sad situation and how can I tell it humorously?"[3]:14

In marriage relationships, his comedies often portray these struggles with plots of marital difficulties or fading love, sometimes leading to separation, divorce and child custody battles. Their endings typically conclude, after many twists in the plot, to renewal of the relationships.[3]:7

Politics seldom have any overt role in Simon's stories, and his characters avoid confronting society despite their personal problems. "Simon is simply interested in showing human beings as they are—with their foibles, eccentricities, and absurdities."[3]:9 Drama critic Richard Eder noted that Simon's popularity relies on his ability to portray a "painful comedy," where characters say and do funny things in extreme contrast to the unhappiness they are feeling.[3]:14

Simon's plays are generally semi-autobiographical, often portraying aspects of his troubled childhood and first marriages. According to Koprince, Simon's plays also "invariably depict the plight of white middle-class Americans, most of whom are New Yorkers and many of whom are Jewish, like himself."[3]:5 He states, "I suppose you could practically trace my life through my plays."[3]:10 In plays such as Lost in Yonkers, Simon suggests the necessity of a loving marriage, opposite to that of his parents', and when children are deprived of it in their home, "they end up emotionally damaged and lost".[3]:13

One of the key influences on Simon is his Jewish heritage, says Koprince, although he is unaware of it when writing. For example, in the Brighton Beach trilogy, she explains, the lead character is a "master of self-deprecating humor, cleverly poking fun at himself and at his Jewish culture as a whole."[3]:9 Simon himself has said that his characters are people who "often self-deprecating and [who] usually see life from the grimmest point of view,"[3]:9 explaining, "I see humor in even the grimmest of situations. And I think it's possible to write a play so moving it can tear you apart and still have humor in it."[6] This theme in writing, notes Koprince, "belongs to a tradition of Jewish humor ... a tradition which values laughter as a defense mechanism and which sees humor as a healing, life-giving force."[3]:9

Characters

Simon's characters are typically portrayed as "imperfect, unheroic figures who are at heart decent human beings", according to Koprince, and she traces Simon's style of comedy to that of Menander, a playwright of ancient Greece. Menander, like Simon, also used average people in domestic life settings, the stories also blending humor and tragedy into his themes.[3]:6 Many of Simon's most memorable plays are built around two-character scenes, as in segments of California Suite and Plaza Suite.

Before writing, Simon tries to create an image of his characters. He said that the play Star Spangled Girl, which was a box-office failure, was "the only play I ever wrote where I did not have a clear visual image of the characters in my mind as I sat down at the typewriter."[12]:4 Simon considered "character building" an obligation, stating that the "trick is to do it skillfully".[12]:4 While other writers have created vivid characters, they have not created nearly as many as Simon did: "Simon has no peers among contemporary comedy playwrights," stated biographer Robert Johnson.[8]:141

Simon's characters often amuse the audience with sparkling "zingers," believable due to Simon's skill with writing dialogue. He reproduces speech so "adroitly" that his characters are usually plausible and easy for audiences to identify with and laugh at.[12]:190 His characters may also express "serious and continuing concerns of mankind ... rather than purely topical material".[12]:10 McGovern notes that his characters are always impatient "with phoniness, with shallowness, with amorality", adding that they sometimes express "implicit and explicit criticism of modern urban life with its stress, its vacuity, and its materialism."[12]:11 However, Simon's characters are never seen thumbing his or her nose at society."[8]:141

Style and subject matter

The key aspect most consistent in Simon's writing style is comedy, situational and verbal, and presents serious subjects in a way that makes audiences "laugh to avoid weeping."[12]:192 He achieved this with rapid-fire jokes and wisecracks,[3]:150 in a wide variety of urban settings and stories.[8]:139 This creates a "sophisticated, urban humor", says editor Kimball King, and results in plays that represent "middle America."[5]:1 Simon created everyday, apparently simple conflicts with his stories, which becamevcomical premises for problems which needed be solved.[5]:2–3

Another feature of his writing is his adherence to traditional values regarding marriage and family.[3]:150 McGovern states that this thread of the monogamous family runs though most of Simon's work, and is one he feels is necessary to give stability to society.[12]:189 Some critics have therefore described his stories as somewhat old fashioned, although Johnson points out that most members of his audiences "are delighted to find Simon upholding their own beliefs."[8]:142 And where infidelity is the theme in a Simon play, rarely, if ever, do those characters gain happiness: "In Simon's eyes, adds Johnson, "divorce is never a victory."[8]:142

Another aspect of Simon's style is his ability to combine both comedy and drama. Barefoot in the Park, for example, is a light romantic comedy, while portions of Plaza Suite were written as "farce", and portions of California Suite are "high comedy".[3]:149

Simon was willing to experiment and take risks, often moving his plays in new and unexpected directions. In The Gingerbread Lady, he combined comedy with tragedy; Rumors (1988) is a full-length farce; in Jake's Women and Brighton Beach Memoirs he used dramatic narration; in The Good Doctor, he created a "pastiche of sketches" around various stories by Chekhov; and Fools (1981), was written as a fairy-tale romance similar to stories by Sholem Aleichem.[3]:150 Although some of these efforts failed to win approval from many critics, Koprince claims that they nonetheless demonstrate Simon's "seriousness as a playwright and his interest in breaking new ground."[3]:150

Critical response

During most of his career Simon's work received mixed reviews, with many critics admiring his comedy skills, much of it a blend of "humor and pathos".[3]:4 Other critics were less complimentary, noting that much of his dramatic structure was weak and sometimes relied too heavily on gags and one-liners. As a result, notes Kopince, "literary scholars had generally ignored Simon's early work, regarding him as a commercially successful playwright rather than a serious dramatist."[3]:4Clive Barnes, theater critic for The New York Times, wrote that like his British counterpart Noël Coward, Simon was "destined to spend most of his career underestimated", but nonetheless very "popular".[12]:foreword

.mw-parser-output .quoteboxbackground-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleftmargin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatrightmargin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centeredmargin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright pfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .quotebox-titlebackground-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:beforefont-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:afterfont-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-alignedtext-align:left.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-alignedtext-align:right.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-alignedtext-align:center.mw-parser-output .quotebox citedisplay:block;font-style:normal@media screen and (max-width:360px).mw-parser-output .quoteboxmin-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important

—Lawrence Grobel[7]:371

This attitude changed after 1991, when he won a Pulitzer Prize for drama with Lost in Yonkers. McGovern writes that "seldom has even the most astute critic recognized what depths really exist in the plays of Neil Simon."[12]:foreword Although, when Lost in Yonkers was considered by the Pulitzer Advisory Board, board member Douglas Watt noted that it was the only play nominated by all five jury members, and that they judged it "a mature work by an enduring (and often undervalued) American playwright."[5]:1

McGovern compares Simon with noted earlier playwrights, including Ben Jonson, Molière, and George Bernard Shaw, pointing out that those playwrights had "successfully raised fundamental and sometimes tragic issues of universal and therefore enduring interest without eschewing the comic mode." She concludes, "It is my firm conviction that Neil Simon should be considered a member of this company ... an invitation long overdue."[12]:foreword McGovern attempts to explain the response of many critics:

Above all, his plays which may appear simple to those who never look beyond the fact that they are amusing are, in fact, frequently more perceptive and revealing of the human condition than many plays labeled complex dramas.[12]:192

Similarly, literary critic Robert Johnson explains that Simon's plays have given us a "rich variety of entertaining, memorable characters" who portray the human experience, often with serious themes. Although his characters are "more lifelike, more complicated and more interesting" than most of the characters audiences see on stage, Simon has "not received as much critical attention as he deserves."[8]:preface Lawrence Grobel, in fact, calls him "the Shakespeare of his time", and possibly the "most successful playwright in history."[7]:371 He states:

Broadway critic Walter Kerr tries to rationalize why Simon's work has been underrated:

Because Americans have always tended to underrate writers who make them laugh, Neil Simon's accomplishment have not gained as much serious critical praise as they deserve. His best comedies contain not only a host of funny lines, but numerous memorable characters and an incisively dramatized set of beliefs that are not without merit. Simon is, in fact, one of the finest writers of comedy in American literary history.[8]:144

Personal life

Simon was married five times, to dancer Joan Baim (1953–1973), actress Marsha Mason (1973–1983), twice to actress Diane Lander (1987–1988 and 1990–1998), and actress Elaine Joyce (1999–2018). His first wife died of bone cancer in 1973.[22] He was the father of Nancy and Ellen, from his first marriage, and Bryn, Lander's daughter from a previous relationship, whom he adopted. His nephew is U.S. District Judge Michael H. Simon and niece-in-law is U.S. Congresswoman Suzanne Bonamici.[23]

Simon was on the board of selectors of Jefferson Awards for Public Service.[24]

In 2004, Simon received a kidney transplant from his long-time friend and publicist Bill Evans.[25]

Neil Simon died on August 26, 2018, after being on life support while hospitalized for renal failure.[26] He also had Alzheimer's disease.[27] He was 91. The cause of death was complications of pneumonia, according to his publicist, Bill Evans. Simon died around 1 a.m. Sunday at New York-Presbyterian Hospital in New York City.[28]

Honors and recognition

Simon held three honorary degrees; a Doctor of Humane Letters from Hofstra University, a Doctor of Letters from Marquette University and a Doctor of Law from Williams College.[29] In 1983 Simon became the only living playwright to have a New York City theatre named after him.[30] The Alvin Theatre on Broadway was renamed the Neil Simon Theatre in his honor, and he was an honorary member of the Walnut Street Theatre's board of trustees. Also in 1983, Simon was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame.[31]

In 1965, he won the Tony Award for Best Playwright (The Odd Couple), and in 1975, a special Tony Award for his overall contribution to American theater.[32] Simon won the 1978 Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture Screenplay for The Goodbye Girl.[33] For Brighton Beach Memoirs (1983), he was awarded the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award,[17] followed by another Tony Award for Best Play of 1985, Biloxi Blues.[32] In 1991 he won the Pulitzer Prize[34] along with the Tony Award for Lost in Yonkers (1991).[32]

The Neil Simon Festival[35] is a professional summer repertory theatre devoted to preserving the works of Simon and his contemporaries. The Neil Simon Festival was founded by Richard Dean Bugg in 2003.[36]

In 2006, Simon received the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor.[37]

Awards

- 1954 Emmy Award nomination for Your Show of Shows[38]

- 1959 Emmy Award for The Phil Silvers Show[34]

- 1965 Tony Award for Best Author – The Odd Couple[32]

- 1967 Evening Standard Theatre Awards – Sweet Charity[34]

- 1968 Sam S. Shubert Award[34][32]

- 1969 Writers Guild of America Award – The Odd Couple[34]

- 1970 Writers Guild of America Award Last of the Red Hot Lovers[34]

- 1971 Writers Guild of America Award The Out-of-Towners[34]

- 1972 Writers Guild of America Award The Trouble With People[34]

- 1972 Cue Entertainer of the Year Award [34]

- 1975 Special Tony Award for contribution to theatre[32]

- 1975 Writers Guild of America Award The Prisoner of Second Avenue[32]

- 1978 Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture Screenplay – The Goodbye Girl[33]

- 1979 Writers Guild of America Award Screen Laurel Award[17]

- 1981 Doctor of Humane Letters from Hofstra University[17]

- 1983 American Theater Hall of Fame[34]

- 1983 New York Drama Critics' Circle Award – Brighton Beach Memoirs[34][17]

- 1983 Outer Critics Circle Award – Brighton Beach Memoirs[17]

- 1985 Tony Award for Best Play – Biloxi Blues[32]

- 1986 New York State Governor's Award[17]

- 1989 American Comedy Awards – Lifetime Achievement[17]

- 1991 Drama Desk Award for Outstanding New Play – Lost in Yonkers[32]

- 1991 Pulitzer Prize for Drama – Lost in Yonkers[34]

- 1991 Tony Award for Best Play – Lost in Yonkers[17]

- 1995 Kennedy Center Honoree[17][33]

- 2006 Mark Twain Prize for American Humor[37]

Work

Simon was credited as contributing writer to at least 49 plays on Broadway:[39]

Theatre

Come Blow Your Horn (1961)

Little Me (1962)

Barefoot in the Park (1963)

The Odd Couple (1965)

Sweet Charity (1966)

The Star-Spangled Girl (1966)

Plaza Suite (1968)

Promises, Promises (1968)

Last of the Red Hot Lovers (1969)

The Gingerbread Lady (1970)

The Prisoner of Second Avenue (1971)

The Sunshine Boys (1972)

The Good Doctor (1973)

God's Favorite (1974)

California Suite (1976)

Chapter Two (1977)

They're Playing Our Song (1979)

I Ought to Be in Pictures (1980)

Fools (1981)

Brighton Beach Memoirs (1983)

Biloxi Blues (1985)

Broadway Bound (1986)

Rumors (1988)

Lost in Yonkers (1991)

Jake's Women (1992)

The Goodbye Girl (1993)

Laughter on the 23rd Floor (1993)

London Suite (1995)

Proposals (1997)

The Dinner Party (2000)

45 Seconds from Broadway (2001)

Rose's Dilemma (2003)

In addition to the plays and musicals above, Simon has twice rewritten or updated his 1965 play The Odd Couple, both of which versions have run under new titles. These new versions are The Female Odd Couple (1985), and Oscar and Felix: A New Look at the Odd Couple (2002).[citation needed]

Screenplays

After the Fox (with Cesare Zavattini) (1966)

Barefoot in the Park (1967) †

The Odd Couple (1968) †

Sweet Charity (1969) †

The Out-of-Towners (1970)

Plaza Suite (1971) †

Last of the Red Hot Lovers (1972) †

The Heartbreak Kid (1972)

The Prisoner of Second Avenue (1975) †

The Sunshine Boys (1975) †

Murder by Death (1976)

The Goodbye Girl (1977)

The Cheap Detective (1978)

California Suite (1978) †

Chapter Two (1979) †

Seems Like Old Times (1980)

Only When I Laugh (1981) ‡

I Ought to Be in Pictures (1982) †

Max Dugan Returns (1983)

The Lonely Guy (1984) (adaptation only; screenplay by Ed. Weinberger and Stan Daniels)

The Slugger's Wife (1985)

Brighton Beach Memoirs (1986) †

Biloxi Blues (1988) †

The Marrying Man (1991)

Lost in Yonkers (1993) †

The Odd Couple II (1998)

- † Screenplay by Simon, based on his play of the same name.[40]

- ‡ Screenplay by Simon, loosely adapted from his 1970 play The Gingerbread Lady.[41]

Television

Television series

Simon, as a member of a writing staff, penned material for the following shows:[40]

The Garry Moore Show (1950)

Your Show of Shows (1950–54)

Caesar's Hour (1954–57)

Stanley (1956)

The Phil Silvers Show (1958–59)

Kibbee Hates Fitch (1965)[42] (pilot for a never-made series; this episode by Simon aired once on CBS on August 2, 1965)

Movies made for television

The following made-for-TV movies were all written solely by Simon, and all based on his earlier plays:[40]

The Good Doctor (1978)

Plaza Suite (1987)

Broadway Bound (1992)

The Sunshine Boys (1996)

Jake's Women (1996)

London Suite (1996)

Laughter on the 23rd Floor (2001)

The Goodbye Girl (2004)

Bibliography

Simon, Neil (1996). Rewrites: A Memoir. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-82672-0.

Simon, Neil (1999). The Play Goes On: A Memoir. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84691-8.

Notes

^ abcd Weltzmann, Deborah (July 4, 2011). "On this day: Neil Simon is born". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

^ abc "About Neil Simon", "American Masters", PBS, November 3, 2000.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaa Koprince, Susan (2002) Fehrenbacher, Understanding Neil Simon, University of South Carolina ISBN 1-57003-426-5.

^ "Neil Simon Unbound — Tablet Magazine – Jewish News and Politics, Jewish Arts and Culture, Jewish Life and Religion". Tabletmag.com. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

^ abcdefghi Konas, Gary (editor) (1997). Neil Simon: A Casebook, Garland Publishing

^ ab Grobel, Lawrence. "Playboy Interview with Neil Simon", Playboy Magazine, Feb. 1977

^ abcdefghijk Grobel, Lawrence, Endangered Species: Writers Talk About Their Craft, Their Visions, Their Lives, Da Capo Press (2001).

^ abcdefgh Johnson, Robert K., Neil Simon, Twayne Publishers, Boston (1983).

^ Grobel, Lawrence. "Neil Simon" Endangered Species: Writers Talk About Their Craft, Their Visions, Their Lives, Da Capo Press, 2009, ISBN 0786751622, pp 381-382

^ The Concise Oxford Companion to Theatre. Eds. Phyllis Hartnoll and Peter Found. Oxford University Press, Oxford Reference Online (1996), New York University. October 18, 2011."Simon, (Marvin) Neil"

^ Ayling, Ronald (2003). Twentieth-Century American Dramatists: Fourth Series. Detroit, Michigan: Gale. ISBN 978-0-7876-6010-9.

^ abcdefghijklmn McGovern, Edythe M. Neil Simon: A Critical Study, Ungar Publishing (1979)

^ "Sweet Charity Broadway @ Palace Theatre - Tickets and Discounts | Playbill". Playbill. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

^ "The Star-Spangled Girl Broadway". Playbill. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

^ "The Odd Couple Broadway". Playbill. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

^ "Barefoot in the Park Broadway". Playbill. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

^ abcdefghij Konas, Gary (1997). Neil Simon: A Casebook. Taylor & Francis. pp. 1–14. ISBN 9780815321323.Azenberg... has produced every one of Neil Simon's 17 plays since 1973's The Sunshine Boys, with number 18 in the works.

^ "'In Defense of Neil Simon': Revisit a Voice Critic's Appreciation of the Late New York Playwright". Retrieved 2018-08-31.

^ Riedel, Michael (April 9, 2010) Simon keeps 'Promises'. New York Post.

^ A Chorus Line: The Story Behind the Show. BerkshireTheatreGroup.org (July 5, 2012).

^ McLean, Ralph. "Cult Movie: Neil Simon's classic comedy The Odd Couple". The Irish News. Retrieved 2018-08-31.

^ Cerio, Gregory (October 9, 1995). "Write of Passage". People. United States: Meredith Corporation.That included not only the pain of her husband's death, but also her mother's. Joan Baim Simon, a Martha Graham dancer who married Neil Simon in 1953, died of bone cancer in 1973 at age 41. Ellen was 16 and her sister Nancy just 10.

^ Mapes, Jeff (May 27, 2011). "Suzanne Bonamici brings financial assets to potential congressional race". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon: Oregonian Media Group. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

^ "Jefferson Awards for Public Service board of selectors 2010". Jefferson Awards for Public Service board of electors. Wilmington, Delaware: Jefferson Awards for Public Service. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

^ Reuters (March 4, 2004). "Neil Simon's pal gives him kidney". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles: Tronc, Inc. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

^ Isherwood, Charles (August 26, 2018). "Neil Simon, a Master of Comedy on Broadway and Beyond, Is Dead at 91". The New York Times. New York City: The New York Times Company. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

^ Kreps, Daniel (August 26, 2018). "Neil Simon, Pulitzer Prize-Winning Playwright, Dead at 91". Rolling Stone. New York City: Wenner Media LLC and BandLab Technologies. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

^ Leopold, Todd (August 26, 2018). "Neil Simon, Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, dies at 91". CNN. Atlanta: Turner Broadcasting System. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

^ Associated Press (June 4, 1984). "Neil Simon Takes His Honorary LL.D with a Grain of Salt". The New York Times. New York City: The New York Times Company. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

^ Simon, Neil (2003). Dennis Kennedy, ed. The Oxford Companion to Theatre and Performance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198601746.

^ Lawson, Carol (May 10, 1983). "Theater Hall of Fame Gets 10 New Members". The New York Times. New York City: The New York Times Company. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

^ abcdefghi Guernsey, Otis L.; Sweet, Jeffrey (1992). The Applause-Best Plays Theater Yearbook, 1990–1991: The Complete Broadway and Off-Broadway Sourcebook. Milwaukee: Applause Books. pp. 183–85. ISBN 978-1557831071.

^ abc Gardner, Elysa (August 26, 2018). "America's playwright Neil Simon, who wrote 'The Odd Couple' and 'Sweet Charity,' has died". USA Today. McLean, Virginia: Gannett Company. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

^ abcdefghijkl Brennan, Elizabeth A.; Clarage, Elizabeth C. (1999). Who's who of Pulitzer Prize Winners. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 131–32. ISBN 9781573561112.

^ "Neil Simon Festival". Simonfest.org. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

^ Orellana, Roxanna (August 1, 2009). "Neil Simon Festival: Cedar City's other festival keeps on with the show". Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

^ ab https://www.voanews.com/a/neil-simon-broadway-s-master-of-comedy-dies-at-91/4544947.html

^ "1954 Emmy nominations for Best Variety Program". Emmy Award. United States: Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (ATAS). February 11, 1954. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

^ "Neil Simon Broadway Credits". Playbill. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

^ abc "Neil Simon: Credits". TV Guide. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

^ "Only When I Laugh". TV Guide. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

^ Kibbee Hates Fitch, Encyclopedia of Television Pilots, 1937–2012, McFarland (2013) p. 2449

References

The Concise Oxford Companion to Theatre. Eds. Phyllis Hartnoll and Peter Found. Oxford University Press, 1996. Oxford Reference Online. Web. York University. October 18, 2011. "Simon, (Marvin) Neil".- Koprince, Susan. Understanding Neil Simon. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2002. 53–60. ISBN 1-57003-426-5.

The Oxford Companion to Theatre and Performance. Ed. Dennis Kennedy. Oxford University Press, 2003. Oxford Reference Online. Web. York University. October 18, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Neil Simon. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Neil Simon |

Neil Simon on IMDb

Neil Simon at the Internet Broadway Database

Neil Simon at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

Neil Simon at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

Appearances on C-SPAN- video: "Neil Simon's Broadway" on YouTube, 6 minutes

- The Neil Simon Festival

- PBS article, American Masters

James Lipton (Winter 1992). "Neil Simon, The Art of Theater No. 10". The Paris Review.

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP