Carolingian art

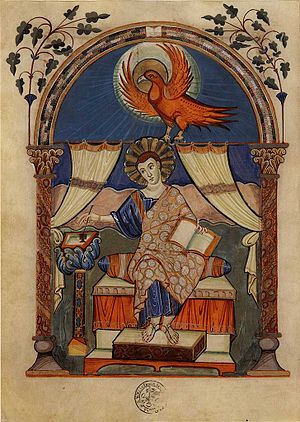

Lorsch Gospels 778–820. Charlemagne's Court School.

Carolingian art comes from the Frankish Empire in the period of roughly 120 years from about 780 to 900—during the reign of Charlemagne and his immediate heirs—popularly known as the Carolingian Renaissance. The art was produced by and for the court circle and a group of important monasteries under Imperial patronage; survivals from outside this charmed circle show a considerable drop in quality of workmanship and sophistication of design. The art was produced in several centres in what are now France, Germany, Austria, northern Italy and the Low Countries, and received considerable influence, via continental mission centres, from the Insular art of the British Isles, as well as a number of Byzantine artists who appear to have been resident in Carolingian centres.

There was for the first time a thoroughgoing attempt in Northern Europe to revive and emulate classical Mediterranean art forms and styles, that resulted in a blending of classical and Northern elements in a sumptuous and dignified style, in particular introducing to the North confidence in representing the human figure, and setting the stage for the rise of Romanesque art and eventually Gothic art in the West. The Carolingian era is part of the period in medieval art sometimes called the "Pre-Romanesque". After a rather chaotic interval following the Carolingian period, the new Ottonian dynasty revived Imperial art from about 950, building on and further developing Carolingian style in Ottonian art.

Contents

1 Overview

2 Illuminated manuscripts

2.1 Centres of illumination

3 Sculpture and metalwork

4 Mosaics and frescos

5 Spolia

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 Further reading

10 External links

Overview

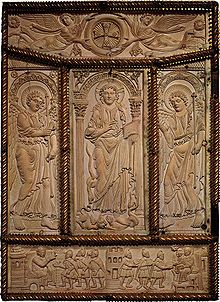

Ivory plaque, probably from a book cover, Reims late 9th century, with two scenes from the life of Saint Remy and the Baptism of Clovis

Having established an Empire as large as the Byzantine Empire of the day, and rivaling in size the old Western Roman Empire, the Carolingian court must have been conscious that they lacked an artistic style to match these or even the post-antique (or "sub-antique" as Ernst Kitzinger called it)[1] art still being produced in small quantities in Rome and a few other centres in Italy, which Charlemagne knew from his campaigns, and where he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in Rome in 800.

As symbolic representative of Rome he sought the renovatio (revival) of Roman culture and learning in the West, and needed an art capable of telling stories and representing figures with an effectiveness which ornamental Germanic Migration period art could not.[2] He wished to establish himself as the heir to the great rulers of the past, to emulate and symbolically link the artistic achievements of Early Christian and Byzantine culture with his own.

But it was more than a conscious desire to revive ancient Roman culture. During Charlemagne's reign the Byzantine Iconoclasm controversy was dividing the Byzantine Empire. Charlemagne supported the Western church's consistent refusal to follow iconoclasm; the Libri Carolini sets out the position of his court circle, no doubt under his direction. With no inhibitions from a cultural memory of Mediterranean pagan idolatry, Charlemagne introduced the first Christian monumental religious sculpture, a momentous precedent for Western art.

Reasonable numbers of Carolingian illuminated manuscripts and small-scale sculptures, mostly in ivory, have survived, but far fewer examples of metalwork, mosaics and frescoes and other types of work. Many manuscripts in particular are copies or reinterpretations of Late Antique or Byzantine models, nearly all now lost, and the nature of the influence of specific models on individual Carolingian works remains a perennial topic in art history. As well as these influences, the extravagant energy of Insular art added a definite flavour to Carolingian work, which sometimes used interlacedecoration, and followed more cautiously the insular freedom in allowing decoration to spread around and into the text on the page of a manuscript.

With the end of Carolingian rule around 900, high quality artistic production greatly declined for about three generations in the Empire. By the later 10th century with the Cluny reform movement, and a revived spirit for the idea of Empire, art production began again. New Pre-Romanesque styles appeared in Germany with the Ottonian art of the next stable dynasty, in England with late Anglo-Saxon art, after the threat from the Vikings was removed, and in Spain.

Illuminated manuscripts

Drogo Sacramentary, c. 850: a historiated initial 'C' contains the Ascension of Christ. The text is in gold ink.

The most numerous surviving works of the Carolingian renaissance are illuminated manuscripts. A number of luxury manuscripts, mostly Gospel books, have survived, decorated with a relatively small number of full-page miniatures, often including evangelist portraits, and lavish canon tables, following the precedent of the Insular art of Britain and Ireland. Narrative images and especially cycles are rarer, but many exist, mostly of the Old Testament, especially Genesis; New Testament scenes are more often found on the ivory reliefs on the covers.[3] The oversized and heavily decorated initials of Insular art were adopted, and the historiated initial further developed, with small narrative scenes seen for the first time towards the end of the period—notably in the Drogo Sacramentary. Luxury manuscripts were given treasure bindings or rich covers with jewels set in gold and carved ivory panels, and, as in Insular art, were prestige objects kept in the church or treasury, and a different class of object from the working manuscripts kept in the library, where some initials might be decorated, and pen drawings added in a few places. A few of the grandest imperial manuscripts were written on purple parchment. The Bern Physiologus is a relatively rare example of a secular manuscript heavily illustrated with fully painted miniatures, lying in between these two classes, and perhaps produced for the private library of an important individual, as was the Vatican Terence. The Utrecht Psalter, stands alone as a very heavily illustrated library version of the Psalms done in pen and wash, and almost certainly copied from a much earlier manuscript.

Other liturgical works were sometimes produced in luxury manuscripts, such as sacramentaries, but no Carolingian Bible is decorated as heavily as the Late Antique examples that survive in fragments. Teaching books such as theological, historical, literary and scientific works from ancient authors were copied and generally only illustrated in ink, if at all. The Chronography of 354 was a Late Roman manuscript that apparently was copied in the Carolingian period, though this copy seems to have been lost in the 17th century.

Centres of illumination

Carolingian manuscripts are presumed to have been produced largely or entirely by clerics, in a few workshops around the Carolingian Empire, each with its own style that developed based on the artists and influences of that particular location and time.[4] Manuscripts often have inscriptions, not necessarily contemporary, as to who commissioned them, and which church or monastery they were given to, but few dates or names and locations of those producing them. The surviving manuscripts have been assigned, and often reassigned, to workshops by scholars, and the controversies attending this process have largely died down. The earliest workshop was the Court School of Charlemagne; then a Rheimsian style, which became the most influential of the Carolingian period; a Touronian style; a Drogo style; and finally a Court School of Charles the Bald. These are the major centres, but others exist, characterized by the works of art produced there.

Saint Mark from the Ebbo Gospels

The Court School of Charlemagne (also known as the Ada School) produced the earliest manuscripts, including the Godescalc Evangelistary (781–783); the Lorsch Gospels (778–820); the Ada Gospels; the Soissons Gospels; the Harley Golden Gospels (800-820); and the Vienna Coronation Gospels; ten manuscripts in total are usually recognised. The Court School manuscripts were ornate and ostentatious, and reminiscent of 6th-century ivories and mosaics from Ravenna, Italy. They were the earliest Carolingian manuscripts and initiated a revival of Roman classicism, yet still maintained Migration Period art (Merovingian and Insular) traditions in their basically linear presentation, with no concern for volume and spatial relationships.

In the early 9th-century Archbishop Ebo of Rheims, at Hautvillers (near Rheims), assembled artists and transformed Carolingian art to something entirely new. The Gospel book of Ebbo (816–835) was painted with swift, fresh and vibrant brush strokes, evoking an inspiration and energy unknown in classical Mediterranean forms. Other books associated with the Rheims school include the Utrecht Psalter, which was perhaps the most important of all Carolingian manuscripts, and the Bern Physiologus, the earliest Latin edition of the Christian allegorical text on animals. The expressive animations of the Rheims school, in particular the Utrecht Psalter with its naturalistic expressive figurine line drawings, would have influence on northern medieval art for centuries to follow, into the Romanesque period.

Another style developed at the monastery of St Martin of Tours, in which large Bibles were illustrated based on Late Antique bible illustrations. Three large Touronian Bibles were created, the last, and best, example was made about 845/846 for Charles the Bald, called the Vivian Bible. The Tours School was cut short by the invasion of the Normans in 853, but its style had already left a permanent mark on other centers in the Carolingian Empire.

From the Utrecht Psalter, 9th-century Naturalistic and energetic figurine line drawings were entirely new, and were to become the most influential innovation of Carolinian art in later periods.

The diocese of Metz was another center of Carolingian art. Between 850 and 855 a sacramentary was made for Bishop Drogo called the Drogo Sacramentary. The illuminated "historiated" decorated initials (see image this page) were to have influence into the Romanesque period and were a harmonious union of classical lettering with figural scenes.

In the second half of the 9th century the traditions of the first half continued. A number of richly decorated Bibles were made for Charles the Bald, fusing Late Antiquity forms with the styles developed at Rheims and Tours. It was during this time a Franco-Saxon style appeared in the north of France, integrating Hiberno-Saxon interlace, and would outlast all other Carolingian styles into the next century.

Charles the Bald, like his grandfather, also established a Court School. Its location is uncertain but several manuscripts are attributed to it, with the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram (870) being the last and most spectacular. It contained Touronian and Rheimsian elements, but fused with the style that characterized Charlemagne's Court School more formal manuscripts.

With the death of Charles the Bald patronage for manuscripts declined, signaling the beginning of the end, but some work did continue for a while. The Abbey of St. Gall created the Folchard Psalter (872) and the Golden Psalter (883). This Gallish style was unique, but lacked the level of technical mastery seen in other regions.

Sculpture and metalwork

Gem-encrusted cover of the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram, 870

Luxury Carolingian manuscripts were intended to have treasure bindings—ornate covers in precious metal set with jewels around central carved ivory panels—sometimes these were donated some time after the manuscript itself was produced. Only a few such covers have survived intact, but many of the ivory panels survive detached, where the covers have been broken up for their materials. The subjects were often narrative religious scenes in vertical sections, largely derived from Late Antique paintings and carvings, as were those with more hieratic images derived from consular diptychs and other imperial art, such as the front and back covers of the Lorsch Gospels, which adapt a 6th-century Imperial triumph to the triumph of Christ and the Virgin.

Important Carolingian examples of goldsmith's work include the upper cover of the Lindau Gospels; the cover of the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram, which can be precisely dated to 870, is probably a product of the same workshop, though there are differences of style. This workshop is associated with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles II (the Bald), and often called his "Palace School". Its location (if it had a fixed one) remains uncertain and much discussed, but Saint-Denis Abbey outside Paris is one leading possibility.[5] The Arnulf Ciborium (a miniature architectural ciborium rather than the vessel for hosts), now in the Munich Residenz, is the third major work in the group; all three have fine relief figures in repoussé gold. Another work associated with the workshop is the frame of an antique serpentine dish in the Louvre.[6] Recent scholars tend to group the Lindau Gospels and the Arnulf Ciborium in closer relation to each other than the Codex Aureus to either.

Charlemagne revived large-scale bronze casting when he created a foundry at Aachen which cast the doors for his palace chapel, in imitation of Roman designs. The chapel also had a now lost life-size crucifix, with the figure of Christ in gold, the first known work of this type, which was to become so important a feature of medieval church art. Probably a wooden figure was mechanically gilded, as with the Ottonian Golden Madonna of Essen.

One of the finest examples of Carolingian goldsmiths' work is the Golden Altar (824–859), a paliotto, in the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio in Milan. The altars four sides are decorated with images in gold and silver repoussé, framed by borders of filigree, precious stones and enamel.

The Lothair Crystal, of the middle of the 9th century, is one of the largest of a group of about 20 engraved pieces of rock crystal which survive; this shows large numbers of figures in several scenes showing the unusual subject of the story of Suzanna.

Mosaics and frescos

Mosaic of the Ark of the Covenant, Germigny-des-Prés, c. 806, but restored. The subject seems drawn from illuminated Jewish bibles, and relates to the Libri Carolini, possibly written by Theodulf, where the Ark is cited as divine approval of sacred images.

Sources attest to the abundance of wall paintings seen in churches and palaces, most of which have not survived. Records of inscriptions show that their subject matter was primarily religious.[7]

Mosaics installed in Charlemagne's palatine chapel showed an enthroned Christ worshipped by the Evangelist's symbols and the twenty-four elders from the Apocalypse. This mosaic no longer survives, but an over-restored one remains in the apse of the oratory at Germigny-des-Prés (806) which shows the Ark of the Covenant adored by angels, discovered in 1820 under a coat of plaster.

The villa to which the oratory was attached belonged to a key associate of Charlemagne, Bishop Theodulf of Orléans. It was destroyed later in the century, but had frescos of the Seven liberal arts, the Four Seasons, and the Mappa Mundi.[8] We know from written sources of other frescos in churches and palaces, nearly all completely lost. Charlemagne's Aachen palace contained a wall painting of the Liberal Arts, as well as narrative scenes from his war in Spain. The palace of Louis the Pious at Ingelheim contained historical images from antiquity to the time of Charlemagne, and the palace church contained typological scenes of the Old and New Testaments juxtaposed with one another.

Fragmentary paintings have survived at Auxerre, Coblenz, Lorsch, Cologne, Fulda, Corvey, Trier, Müstair, Mals, Naturns, Cividale, Brescia and Milan.

Spolia

Lorsch Gospels. Ivory book cover. Late Antiquity Imperial scenes adapted to a Christian theme.

The Lothair Crystal, mid-9th century

Spolia is the Latin term for "spoils" and is used to refer to the taking or appropriation of ancient monumental or other art works for new uses or locations. We know that many marbles and columns were brought from Rome northward during this period.

Perhaps the most famous example of Carolingian spolia is the tale of an equestrian statue. In Rome, Charlemagne had seen the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius in the Lateran Palace. It was the only surviving statue of a pre-Christian Roman Emperor because it was mistakenly thought, at the time, to be that of Constantine and thus held great accord—Charlemagne thus brought an equestrian statue from Ravenna, then believed to be that of Theodoric the Great, to Aachen, to match the statue of "Constantine" in Rome.

Antique carved gems were reused in various settings, without much regard to their original iconography.

See also

- Carolingian architecture

- Codex Vaticanus 3868

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carolingian art. |

Notes

^ Kitzinger, 8

^ Kitzinger, 40–42

^ Kitzinger, 69. Dodwell, 49 discusses the reasons for this.

^ Dodwell, 52

^ Lasko, 60–68

^ Lasko, 64-65, 66-67; picture of the dish

^ Dodwell, p. 45

^ Beckwith, 13–17

References

- Beckwith, John. Early Medieval Art: Carolingian, Ottonian, Romanesque, Thames & Hudson, 1964 (rev. 1969), ISBN 0-500-20019-X

- Dodwell, C.R.; The Pictorial Arts of the West, 800–1200, 1993, Yale UP, ISBN 0-300-06493-4

- Gaehde, Joachim E. (1989). "Pre-Romanesque Art". Dictionary of the Middle Ages. ISBN 0-684-18276-9

- Hinks, Roger. Carolingian Art, 1974 edn. (1935 1st edn.), University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-06071-6

Kitzinger, Ernst, Early Medieval Art at the British Museum, (1940) 2nd edn, 1955, British Museum- Lasko, Peter, Ars Sacra, 800-1200, Penguin History of Art (now Yale), 1972 (nb, 1st edn.) ISBN 978-0-14056036-7

"Carolingian art". In Encyclopædia Britannica Online

Further reading

Holcomb, M. (2009). Pen and Parchment : Drawing in the Middle Ages. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (see index)

External links

- Ross, Nancy, Carolingian Art, Smarthistory, undated

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP